Overcoming apartheid – lessons for Auroville?

FeatureBy Alan

Keywords: Apartheid, Race / racism, South Africa, World history, Community interaction, Conflict resolution, Africa, Freedom, Injustice, Reconciliation and Forgiveness

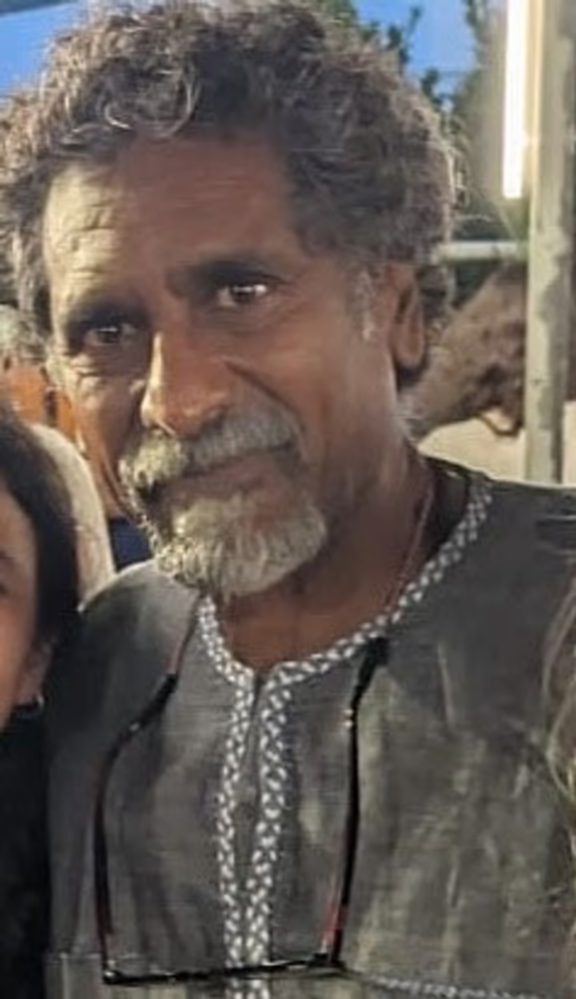

Jay Naidoo

Jay: The healing of all of us has to become the priority for the way forward. When I was four years old my family was evicted from our home because of the social engineering experiment of apartheid. It left a very deep impression upon me and a very deep wound that I carried for a long time. And its expression was anger because three million people were evicted from their homes, and millions of families and workers were broken when the migrant labour laws were brought in. It (the idea of being an inferior race) also became a wound in which we started to believe, and that is why Africa has suffered so terribly from colonisation.

But I was fortunate that I met somebody who is as important in our lives as Nelson Mandela: Steve Biko. When I was 15 I went to a meeting and this amazing charismatic student leader said something that I will remember as if it was yesterday. That the mind of the oppressed is the main weapon in the hands of the oppressor, that the colour of our skin does not make us inferior, and we can lose the chains that bind us by an exploration of our inner self.

He lit a spark which started me on a life journey, and also the millions who became known as the generation of 1976 who rose up to oppose apartheid. We thought we could defeat the system, but in our ego and ignorance we left behind our parents, our workers, and the rural people. That realisation changed my life trajectory. I became a volunteer in a union movement that was still illegal for African workers to join. Later I became the leader of one of the largest union of workers on the African continent, one that became the backbone of our struggle for freedom.

Through that I understood what my role was, which was to create the conditions in which one day we could rise above our constituencies, tame our egos and understand that we have a possibility of a transition which was peaceful, in spite of our anger.

However, in 1989 we were approaching a situation like a racial civil war in our country. So Mandela’s release presented us with a unique opportunity.

I was the first to arrive at his prison. It was an amazing experience to be greeted by someone who represented everything your life had been about. He walked out to this huge phalanx of the press and the first question was, “Do you have any feelings of revenge after you have been put in prison for 27 years?” His response was classic Mandela. “If I have revenge in my heart when I leave this prison, I will still be a prisoner.”

Later, I sat in the cabinet with the same people who had had me on their death list and were responsible for the deaths of many people I knew, so I’m often asked the same question. And I answer in the same way.

I never wanted to go into government, but Mandela asked me to. There I learned that the search for power and the access to power do not resolve conflict in society, so when he left I left.

I was very fortunate. I thought I would die when I was 36, but then I meet Lucie. She transformed me because up till then I was just a machine, with a total focus on freedom. But through meeting her I understood that freedom is much more than the political freedom we fight for. She humanised me and brought me on a journey to understand who I am.

So here I am, continuing the search for who I am, where I am going, and what defines my humanity. And this is what attracted me when I first encountered the philosophy of Mother and Sri Aurobindo many years ago.

Heal yourself and forgive

Lucie: My greatest lesson in South Africa, and what changed my life, was Nelson Mandela’s 85th birthday. In that crowd I saw his jailer, I saw the chief of the party that had kept him in prison for so long, and I saw one of the ministers responsible for killing his comrades. When I saw how he treated those people, it changed my life. There was a card on the tables with his favourite proverb. The proverb said, ‘eat your breakfast alone’, because it’s important to have some time in the day when you can consider who you are and what you are doing; ‘share your lunch with your friends’, because this reflects solidarity; but ‘give your supper to your enemies’, because you have to live with them, and you have to accept that no one has exactly the same ideas as you, but we live on a shared land.

That proverb gave me the courage to heal myself and to forgive those who had oppressed me. I understood that with whoever is in front of you there is always a bridge to build, there is always something that unites us. We live in a world where we look at the differences, but if we look at what is the same, then we can start building the road.

Forgiveness for me has been the greatest liberator. Forgiving is not accepting what the other person did. Forgiveness is cutting the energetic link with the event or the person so that you can continue with your life. Mandela said that when you want the other one to die, you drink the poison.

Gogo: When I hear about the great ones of South Africa, like Mandela and Biko, I realise that they are living quintessentially the principle of ubuntu. At the very core ubuntu says “I am because you are”. And that means that there is no other. There is no discrimination, no separation, no segregation.

But the human aspect accounts for only about a quarter of what ubuntu represents, for the suffix untu refers to the dynamic life force, the causeless cause, the origin that weaves through all creation. Untu manifests in the grass, the flowers and in trees, in time and space, and in modal forces like beauty, fear, anger and love. So ubuntu is the quantum principle that holds all conflict resolution.

In conflict resolution, we use the principle we call ‘circumspection’, which is how we view things according to indigenous African cosmology. So, firstly, we have segregation, which is represented by a deity who is always looking for the external differences. Then we have a female deity who is always looking to see what the similarities are, but doesn’t take into consideration what may be inner differences. Another deity is the warrior and he engages in analysis, which from an African perspective is the ability to see the inner differences. And then we have another female deity who engages in synthesis – the ability to see the inner similarities in spite of outer differences.

Circumspection engages all of these: it is the ability to see from all angles. So in conflict resolution we are always seeking to have a circumspective view of any situation, including a circumspect view of our inner selves.

Mandela’s release

Aurovilian: It seems that Mandela’s release from prison was a turning point. How did that come about?

Jay: There was this global explosion in the 1960s which manifested in massive anti-war protests and the great liberation heroes. Steve Biko translated that into what became the Black Consciousness movement. It was a watershed of the modern South African struggle, for it created a new cadreship of leaders who built from the grassroots. We were a generation prepared to die for freedom, so we created a very powerful mass democratic movement. Organising is actually the art and science of coalition building, and we constructed this huge ‘tent’ in which there were communists, capitalists, trade unionists and nationalists: everyone who felt they could contribute something to what we were fighting for, which was ‘one person, one vote’.

We didn’t defeat the apartheid regime, we didn’t march to Pretoria on the backs of tanks. Rather, we achieved a political stalemate where they could not defeat us and we could not defeat them.

Also, when the Berlin Wall fell, it meant the West no longer had to support a white apartheid regime as a bulwark against communism, and this created the opportunity for Nelson Mandela to be released.

Lucie: Also, because of the international sanctions, South Africa was bankrupt by the end of the 1980s. Somebody had to put a key in the door of Mandela’s cell and open it. That man was De Klerk. But at the back of his mind he thought he could impose a veto on behalf of the white people on the principle of one man, one vote. He failed because this was seen as just another form of apartheid, and that is why De Klerk left the government.

Jay: Meanwhile, the country was falling into deeper and deeper conflict, and at one point there was recognition on both sides that if we continued like this, we would have no country to govern. This meant that each one of us had to rise above our constituencies.

We needed leaders we could trust, so we gravitated towards those, like Mandela, who were a spectacular example of servant leadership, who through great personal sacrifice had built the foundation of what we did.

Leadership is not about always swimming with the current. It is when you have the courage to swim against it, guided by an inner wisdom. For example, when Mandela was released, violence enveloped the country. This was due to the resistance of a very powerful element of right-wing groups and their allies who felt Mandela’s release was a complete sell-out. But at a certain point, Mandela announced at a huge meeting in Durban, where the violence was worst, that we must unilaterally suspend the armed struggle, and “throw all our arms into the sea”. There was fierce resistance to this, even from within our own leadership, because this was an important aspect of our struggle, and this was at a time when people in the townships were being killed.

Even I was a bit skceptical. But his argument was solid, for if we had continued on that line, we would have had even more casualties and the country would have fallen apart.

The way to reconciliation

Aurovilian: How did you get people responsible for atrocities to participate in the Truth and Reconciliation process?

Jay: It came to a point where we had to make a decision about all the atrocities that happened in our past. We looked at all the literature and experience of the world, including the Nuremberg Trials. These were a way of punishing people accused of atrocities so that never again would that trauma be repeated.

But we didn’t take that route. For, like Sri Aurobindo, the revolutionary Mandela had been transformed by the time he spent in a prison cell. During that time, he studied the language of the oppressor, he read the Upanishads, he had understood so much about life, and now he knew who he was and how he wanted to live his life.

When he was released, many people wanted revenge, but he advocated a process of reconciliation. We chose the route we call ‘amnesty’. If you came forward and presented yourself before a panel, led by Archbishop Tutu, and said this is what you did, and there was a political reason why you did it, and you were following instructions, then you were granted amnesty for the crime that was committed. Some people felt this just meant you were going to give in to the other side. But for Mandela it meant more than giving in or just forgiving. It took great courage because it involved apology, meaning an acknowledgement that people saw, understood, those whom they had been oppressing or mistreating. It was about making reparation. Mandela taught us to release anger in a way that allowed a path to reconciliation.

This was a process we felt would allow us to go forward because the country at that moment was extremely fragile. There were two opposing paths. The white minority wanted a veto right on any democracy, while our principle was one person, one vote, in a nonracial South Africa. So the question was how to find common ground, because it is very easy to find differences. But if you descend from the mind to the heart and open up your heart, what you ultimately find is unity of purpose and our common humanity, and this can become the foundation for transcending our differences.

Therefore the Commission, while imperfect, was the basis for powerful reconciliation between white and black. And this was celebrated in the 1994 election, when we all stood in line – white, Indian and black, fighter and oppressor – and we all started to talk to each other. That was the victory of taking that route.

The inner reason for conflict

Aurovilian: This happened when apartheid was no longer an option. But what is happening in Auroville today is a small group of people feel that oppression is an option and the way to get things done. This is what we are struggling with.

Jay: This is your challenge. I have always been part of community building, nation building. If I look at my own country today and see how far we have fallen from the great ideals that Mandela represented, I ask myself, how can we have such leaders? And I have come to the conclusion that it’s because we deserve them. So what function do they play? I turn again to The Mother’s wisdom who said that everything, even the asuras, are part of a divine creation and they are here to test our sincerity.

Mandela’s intention was to crystallise a new consciousness in the country. We haven’t really succeeded in that, but it doesn’t mean we failed. It means our sincerity is being tested.

So I see that all you are going through now is for a reason, which is to advance yourselves in your consciousness, in spite of how much pain it causes. If you can separate yourselves from the pain, the trauma, and learn the lesson and rise above it, like we did in South Africa, there’s always something better that you will evolve to than where you are at the moment.

But are we looking for another Messiah to come to the rescue? Another Mother, another Mandela?

Our son gave me the answer at Mandela’s funeral. He said there has been a genocide of human values, which is why we face what we face. But don’t look for another Mandela, he said, he won’t come. Rather make the Mandela inside you come out, for we all have Mandela qualities. We all have Mother qualities.

My most painful experiences have been my greatest teachers. And I’ve learnt that whatever I dislike in another is my own ego, my feeling of aggrievement, my feeling of anger, and that I have to find a way to put myself in the shoes of that person.

I experienced this in Mandela’s cabinet. One of the ministers was a man whose organisation had killed people I had trained, and I ended up sitting next to him. Then I thought, who am I to judge? If Mandela had appointed him and he had been respectful enough to accept Mandela as President, even though this man had the potential to destabilise the whole country, who was I to judge? Therefore, I learned that my role was to follow the lead of Mandela and to find a way to work with that person. Because then the larger question is, whose truth is in the room? Is there only one truth? Do we believe we carry the absolute truth?

So we need to find a way not to build bridges but to become the bridge. Now I have to see what I have to unlearn, what I have to change in my behaviour, so that I am able to be the bridge between the rising tensions in my own country.

Lucie: One exercise I do is to send pure love to somebody who has oppressed me, because obviously that is what is missing in their life. Everything is about energy. If you express anger towards that person, they will use that energy to direct it back towards you. So if, instead, you give them love, that is what eventually will come back. That’s the only way out.

Jay: That’s exactly what I learned; it is how I liberated myself from deep anger. Now I’m at peace with myself and everything around me. I only want to open my heart to the divine love, for it is a tool to conquer everything. It’s not easy to practice, but Auroville is too precious to waste this experiment: it’s too precious for the world. For in the world today we are at the edge of a precipice.

I wrote a book about my message to the next generation. It had to be one without anger, and one in which I admit my complicity in what I’ve been responsible for, because all conflict is cause and effect. Nation building, community building, is about finding the unifying web, the mycelium to build an organism that is constantly replicating itself through its consciousness. And then it will become a community of divine practice rather than a community of interests, because that is what always leads to these clashes.

The courage of servant leadership

Aurovilian: You said that at a certain point in South Africa there was a stalemate when both sides understood there was no way forward except to reconcile. What if, as in Auroville’s present situation, that realisation is not there yet? How do we accelerate the process to get to that point?

Jay: I think you have a unique opportunity here to take the debate to a higher level than is happening in the rest of the world.

The question you have to ask yourself is, are you waiting for an invitation or are you extending an invitation? If you are waiting because you feel hurt, you are not acknowledging that there may be hurt on the other side. Isn’t it easier just to swallow the ego a bit, to tame it and say, okay, if there is an opportunity to sit around a table, can I go into that conversation with my heart and not my head? And open myself up to Divine Grace, to surrender to Divine Love?

The real courage of ‘servant leadership’, which is what Mandela embodied, is to stand up and say, ‘I invite you to a conversation where there are no conditions, where I want to express myself and I want you to express yourself. And I want us to think about what I am prepared to do to make peace with you, and then you tell me what you are willing to do to make peace with me. I acknowledge there are differences, but I also acknowledge that we all say we are inspired by Sri Aurobindo and The Mother’.

I think self-growth is the most important thing which The Mother talked about. If you feel that something is not working, what are you going to do to fix it without the expectation that somebody is going to come and prostrate themselves before you first? We didn’t expect De Klerk to apologise to Mandela; that wasn’t the issue for us. The issue was, can I negotiate with you so that we can get to a shared vision? It took a long, long time, with many people dying, before that happened.

You don’t face those situations here, so just get on with what you need to do now. When there’s a problem, solve it by opening your hearts.

Indigenous conflict resolution

Jay: In the indigenous tradition we work with shamans of the Sand People. They are hunter gatherers and when they have a conflict, even a serious crime like a murder, everybody in the community, including the children, come to sit under the tree in the desert and all have a say. They don’t have jails or policeman or courts. The intention is to solve it, and when there is a penance to be paid, the entire community, including the perpetrator and the victim’s families, has to agree to it. In this way, they retain the integrity of the community.

Gogo: Many spiritual leaders contributed their wisdom to making a peaceful transition in South Africa. Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa [a traditional Zulu healer from South Africa who passed away in 2020, eds.] talked about what happens when, for example, a serial killer is brought into the court of a certain community. They would take the serial killer into the birthing hut and allow him to sit in the hut, away from the pregnant woman, for the duration of her labour, ensuring that he hears every scream. And once the baby is born, the first person who catches the baby is the serial killer because they want him to experience what life smells like, feels like. Their understanding is that he is killing because he has lost the principle of life. So if we bring life to him in its purest form, he will be reformed.

This is healing as opposed to punishing. It is seeing the root of the problem, and therefore getting to the root of the solution.

Vusamazulu suffered many atrocities, both at the hands of the apartheid regime as well as the revolutionaries. But his main message was that the future can be changed because the future lies in each one of us. And it all ripples down to “I am because you, we, are”.

The African Pavilion

Jay: We were very disheartened that the African pavilion in Auroville’s International Zone has disintegrated, and why more Africans are not part of this international experiment. It is not about blaming, but you have to ask yourself in your hearts, what are you doing that doesn’t make us feel welcome? Is it because you believe that because we come from Africa that we don’t have spirituality? That is a very racial construct.

Gogo: Colonialism did an atrocious trick upon Africa and made it believe it was the ‘Dark Continent’. But it is in Africa that we first see civilisation growing. Here we see the first evidence of human interaction, the oldest lunar calendar, and the oldest solar calendar, which predates Stonehenge by 70,000 years. All of this knowledge and much more have been hidden, and part of what we are doing is explicating it and showing how we all are one, ubuntu, which is bringing everything back to that knowledge of the first time.

Stay focused on the vision

Jay: I think this is the kind of wisdom we need to call on at this moment when we are facing so many momentous challenges in the world. We need to keep focused on the vision, the lodestar, that will take us to the next step in our evolution. If we don’t do that in this generation, our species will not survive. I’m not worried about Mother Earth, although it will take a hundred million years for it to recover from our stupidity. The question is, have we earned the right to be here?

In my day, the big question was, are you ready to die for freedom? Today, in my dialogue with young people, I ask them, what are you prepared to live for?

The Mother never intended that the unique experiment of Auroville stops here. She wanted it to become a self-replicating mycelium which would infect the whole world. So we would like you to share it with us, we would lik to send people grounded in our cosmology to learn from you, but also to complete you. For when you are completed you will have the wisdom of many traditions, many lineages, and maybe the problems that you face today will have many other solutions.

We want a genuine, authentic collaboration and intelligent dialogue with you. In helping consolidate you, we would be giving you the protection of everything we come from. And we would be taking Mother’s vision to its logical conclusion, which is helping humanity at a very precarious moment.