Sri Aurobindo and the Savitri Legend

FeatureBy Richard Hartz

Keywords: Savitri — A Legend and a Symbol, Sri Aurobindo’s life, Indian culture, The Mahabharata, Tales and stories, Spiritual poetry, Love, Words of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, Symbols, The Vedas, Spiritual experiences, Supramental transformation, Archetypes, Adverse forces, Spirit, Idealism and Transformation

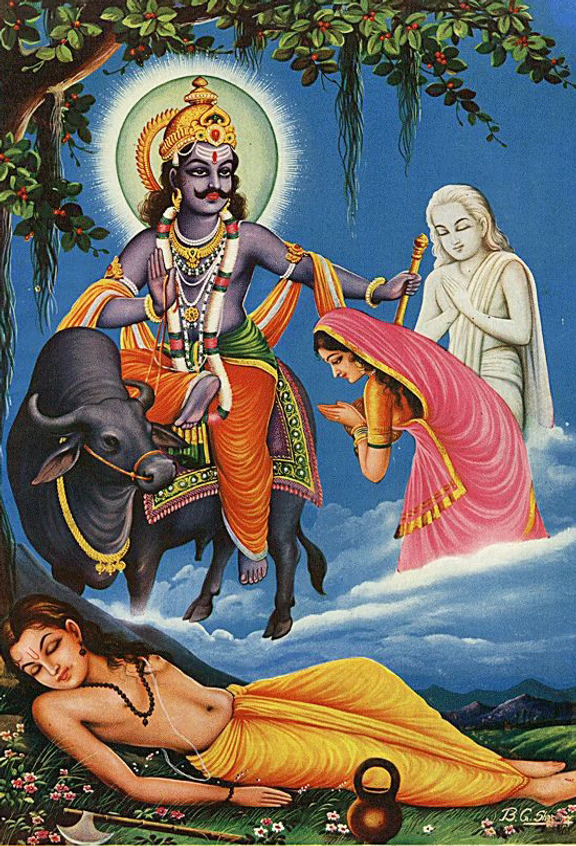

Death claims Satyavan’s soul while Savitri pleads for his return to life

The young Aurobindo Ghose spent his student years in late nineteenth-century England steeped in the only literatures that were readily accessible to him there: those of ancient, medieval and modern Europe, many of whose works, especially their poetry, he read in the original languages. Europe then dominated the world and the path to success, as mapped out for Aurobindo by his anglophile father, lay through the ability to present oneself, culturally, as an accomplished Westerner. Even when his life veered in a radically different direction after his return to India in 1893 at the age of twenty, the imprint left by his formative immersion in Western culture remained indelible and left its stamp on all his subsequent political, poetic and philosophical writings.

The world would never have heard of Aurobindo, however, if he had not reinvented himself as a result of discovering his roots in the literary, intellectual and spiritual cultures of India. Though he continued to think and write mainly in English, the influence of his motherland, exerted upon him largely through the medium of Sanskrit, soon came to dominate the elements in his mental makeup that he owed to growing up in the West. Early in this indigenisation process he plunged into the popular Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. It was in the latter that he came across a theme that would continue to haunt him until he made it the subject of an epic of his own. This was the story of Savitri, the young woman who defied the god of Death and brought her husband, Satyavan, back to life.

The tale of Savitri and Satyavan had already acquired various levels of meaning in the course of its long history in the Indian tradition. By his creative engagement with it, Sri Aurobindo would further enrich the ancient legend with a new layer of significance. But his starting-point was an appreciation of the episode as told in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata. However far his reinterpretation of the story might eventually travel from what he had encountered in his initial exploration of Sanskrit literature, elements of the oldest extant version attributed to Vyasa remain as essential features of Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol. These include not only the main outline of the plot and a number of specific details, but also a certain stylistic influence of what Sri Aurobindo took to be Vyasa’s writing.

In Notes on the Mahabharata, written around 1902, he summed up the characteristics of Vyasa’s “granite mind”: “In his austere self-restraint and economy of power he is indifferent to ornament for its own sake, to the pleasures of poetry as distinguished from its ardours, to little graces & self-indulgences of style; the substance counts for everything & the form has to limit itself to its proper work of expressing with precision & power the substance.” These were qualities that Sri Aurobindo evidently admired and found worthy of emulation when he came to write poetry on an epic scale himself, albeit in a language very different from Sanskrit. Fused with other influences from Indian and Western literatures, ancient and modern, an echo of what he took to be the authentic Mahabharata style can be identified as a component of the poetics of Savitri.

Regarding the Savitri episode itself, we find in Notes on the Mahabharata this comment on Vyasa’s treatment of the subject: “In the Savitrie (sic) what a tremendous figure a romantic poet would have made of Death, what a passionate struggle between the human being and the master of tears and partings! But Vyasa would have none of this; he had one object, to paint the power of a woman’s silent love and he rejected everything which went beyond this or which would have been merely decorative. We cannot regret his choice. There have been plenty of poets who could have given us imaginative and passionate pictures of Love struggling with Death, but there has been only one who could give us a Savitrie.” In Sri Aurobindo’s hands, during the course of his work on Savitri between 1916 and 1950, the legend is transfigured and raised to another plane altogether. But the dauntless strength of character of the Kshatriya princess Savitri herself and the quiet, unshakable intensity of her love remain constant, universalised to represent the power of the goddess in all women. When Death leads Satyavan’s soul into his own dark realm, she follows them:

The Woman first affronted the Abyss

Daring to journey through the eternal Night....

Solitary in the anguish of the void

She lived in spite of death, she conquered still....

Her limbs refused the cold embrace of death,

Her heart-beats triumphed in the grasp of pain;

Her soul persisted claiming for its joy

The soul of the beloved now seen no more.

A Myth of the Vedic Cycle?

The role of the Mahabharata as a source and inspiration for Savitri is indisputable, but by itself it accounts for only one dimension of the epic. What Sri Aurobindo had in mind when, almost half-way through his work on the poem, he gave it the subtitle, A Legend and a Symbol, is suggested by a note found among his manuscripts of the mid-1940s and published in recent editions as an “Author’s Note”. It begins: “The tale of Satyavan and Savitri is recited in the Mahabharata as a story of conjugal love conquering death. But this legend is, as shown by many features of the human tale, one of the many symbolic myths of the Vedic cycle.”

The uncovering of a mystical symbolism in the characters and events of the narrative opened up unexpected vistas of meaning and eventually made it possible for Savitri to evolve into something like a poetic counterpart of the philosopher-sage’s monumental prose work, The Life Divine. Between his reading of the Mahabharata episode and his preliminary sketches of an original poem based on it, Sri Aurobindo had made a deep study of the Rig Veda. While this research was continuing, he published its results serially under the title The Secret of the Veda from August 1914 to July 1916, a month before the date of the opening of the first draft of Savitri.

That Savitri is interspersed with Vedic imagery is beyond question. In passages such as these lines on the goddess of inspiration, a familiarity with The Secret of the Veda on the part of the reader seems almost to be taken for granted:

In the deep subconscient glowed her jewel-lamp;

Lifted, it showed the riches of the Cave

Where, by the miser traffickers of sense

Unused, guarded beneath Night’s dragon paws,

In folds of velvet darkness draped they sleep

Whose priceless value could have saved the world.

A darkness carrying morning in its breast

Looked for the eternal wide returning gleam,

Waiting the advent of a larger ray

And rescue of the lost herds of the Sun.

The third line of this passage reproduces almost verbatim the wording of what is said in The Secret of the Veda about the Panis, creatures of the cave, depicted as “miser traffickers in the sense-life, stealers and concealers of the higher Light and its illuminations”. Other Vedic allusions in these lines include references to the serpent or dragon Vritra, “the personification of the Inconscient”, and to Usha, the goddess of Dawn. The last line relates again to the legend, examined in depth in The Secret of the Veda, “of the recovery of the lost cows from the cave of the Panis by Indra and Brihaspati with the aid of the hound Sarama and the Angiras Rishis”.

But even more central to the poem than such allusions is the notion that the story itself, as it appears in the Mahabharata, is a retelling of a primordial myth passed down from an age that expressed an archaic wisdom in the language of symbols. Sri Aurobindo seems to have intended to give this immemorial symbolism a new lease on life in Savitri, fusing it with his own futuristic vision of a kind of spiritual transhumanism.

The starting-point for his re-conceptualisation of the Savitri legend as a Vedic myth resonating with his own philosophy was a recognition of the Vedic associations of the names of the main personages, especially Savitri and Satyavan themselves. Sāvitrī means “daughter of the Sun”, the Sun being in Sri Aurobindo’s reading of the Veda an image for what he terms the supramental consciousness. Satyavān, literally “he who possesses the truth”, is explained in the context of the story as “the soul carrying the divine truth of being within itself but descended into the grip of death and ignorance”. Sri Aurobindo evidently saw in Satyavan’s return from the realm of Night a parallel to the event described in the Vedic hymns as the discovery and liberation of “that truth satya even the Sun dwelling in the darkness”. This founding achievement of the Vedic religion was celebrated by the Rishis as the work of their forefathers in collaboration with the gods. The result was the forging of a path to immortality, represented as a state in which not only the inner consciousness, but even the physical being “breaks its limits, opens out to the Light and is upheld in its new wideness by the infinite Consciousness, mother Aditi, and her sons, the divine Powers of the supreme Deva”.

Looking for confirmation of his experiences and aspirations in past traditions, Sri Aurobindo discerned in this imagery a foreshadowing of his own search for the way to a supramental transformation. The supramental change, as he envisaged it, will take place “when the involved supermind in Nature emerges to meet and join with the supramental light and power descending from Supernature”. Miraculous as this may sound, it is a logical extension of the idea in his philosophy of evolution that “the development of life, mind and spirit in the physical being presupposes ... two co-operating forces, an upward-tending force from below, an upward-drawing and downward-pressing force from above”. Savitri, incarnating the goddess who in the reconstructed Vedic myth “comes down and is born to save”, would seem to represent the “force from above”.

But after briefly offering this key to some of the symbolism underlying his poem, Sri Aurobindo hastens in the Author’s Note to clarify that “this is not a mere allegory”. Allegory, he explains elsewhere, “comes in when a quality or other abstract thing is personalised and the allegory proper should be something carefully stylised and deliberately sterilised of the full aspect of embodied life....” In contrast to allegory, which must “be intellectually precise and clear”, a symbol expresses “not the play of abstract things or ideas put into imaged form, but a living truth or inward vision or experience of things, so inward, so subtle, so little belonging to the domain of intellectual abstraction and precision that it cannot be brought out except through symbolic images”. Symbolism reaches its height in mystic poetry, where “the symbol ought to be as much as possible the natural body of the inner truth or vision, itself an intimate part of the experience”. Attempting in Savitri to write mystic poetry on an epic scale, Sri Aurobindo faced the challenge of sustaining a symbolic meaning without allowing the narrative to become stylised and sterilised in the manner of an allegory.

The Great Negation

Death appears at first sight to be the villain of the story. His shadowy figure represents an aspect of existence that has to be confronted and defeated. He is the great divider and nihilist. Yet the poet also recognises death’s positive function as “an instrument of perpetual life”:

Although Death walks beside us on Life’s road,

A dim bystander at the body’s start

And a last judgment on man’s futile works,

Other is the riddle of its ambiguous face:

Death is a stair, a door, a stumbling stride

The soul must take to cross from birth to birth,

A grey defeat pregnant with victory,

A whip to lash us towards our deathless state.

Writing in The Life Divine as a philosopher rather than as a poet, Sri Aurobindo explains “the necessity and justification of Death, not as a denial of Life, but as a process of Life”, though he also endorses the ideal of “an exceeding of the law of the physical body, – the conquest of death, an earthly immortality”.

But for the purposes of the central symbolic narrative of Savitri, Death and the Woman are “the great opponents”. Addressing each other often with scornful irony, they seem to be locked in an existential struggle in which one or the other must perish. The atmosphere of their confrontation is far from that of the respectful, though sometimes tense, dialogue recounted in the Mahabharata. There Savitri, archetype of the devoted wife (pativratā), wins back her ill-fated husband from Yama, the god of death who is also the lord of dharma, the social and moral law, by pleasing him with her virtue and intelligence. Yama’s power is undiminished by the boons he grants, including the revival of Satyavan.

In Sri Aurobindo’s poem, on the other hand, the figure of Death is represented not in terms of the traditional religious conception of Yama, but as “embodied Nothingness,” the “great Negation” or “the contemptuous Nihil”. Savitri, in turn, does not incarnate a socio-ethical ideal as in the Mahabharata, an epic of what Sri Aurobindo calls the typal age; much less does she fit the stereotype of the dutiful wife to which she was paradoxically reduced by the conventionalism of a later period of the decline of Indian civilisation. The Savitri we meet in Sri Aurobindo’s poem is the embodiment of a spiritual force. The outcome of her encounter with death points towards the possibility of a fundamental change in the balance of forces in earthly life which would ultimately deprive death of its right to have the last word on all things.

When Satyavan has passed from Savitri’s embrace, it is as a “denial of all being” that Death first makes his presence felt:

Something stood there, unearthly, sombre, grand,

A limitless denial of all being

That wore the terror and wonder of a shape....

His shape was nothingness made real, his limbs

Were monuments of transience and beneath

Brows of unwearying calm large godlike lids

Silent beheld the writhing serpent, life....

The two opposed each other with their eyes,

Woman and universal god....

Savitri’s first words, when she finally speaks, establish the combative tone of the exchanges that follow:

“I bow not to thee, O huge mask of death,

Black lie of night to the cowed soul of man....

Not as a suppliant to thy gates I came:

Unslain I have survived the clutch of Night....

Now in the wrestling of the splendid gods

My spirit shall be obstinate and strong

Against the vast refusal of the world.”

As in The Life Divine, so in Savitri, Sri Aurobindo sets out to reconcile Matter and Spirit, overcoming the opposition between two negations that have exerted a powerful influence on the course of civilisation in the West and in the East: the materialist denial of Spirit and the ascetic rejection of material life. Both ideologies in their extreme forms give a semblance of justification to the nihilistic claim of Death:

“Two only are the doors of man’s escape,

Death of his body Matter’s gate to peace,

Death of his soul his last felicity.

In me all take refuge, for I, Death, am God.”

An other-worldly spiritual view of things lends itself admirably to Death’s insistence on the futility of human life and love:

“One endless watches the inconscient scene

Where all things perish, as the foam the stars.

The One lives for ever. There no Satyavan

Changing was born and there no Savitri

Claims from brief life her bribe of joy. There love

Came never with his fretful eyes of tears....

Live in thyself; forget the man thou lov’st.

My last grand death shall rescue thee from life....”

But scientific materialism is equally inhospitable to the dreams of the idealist. Death turns it to his advantage with devastating effect:

“When all unconscious was, then all was well.

I, Death, was king and kept my regal state,

Designing my unwilled, unerring plan....

Then Thought came in and spoiled the harmonious world:

Matter began to hope and think and feel,

Tissue and nerve bore joy and agony....

O soul misled by the splendour of thy thoughts,

O earthly creature with thy dream of heaven,

Obey, resigned and still, the earthly law....

There shall approach silencing thy passionate heart

My long calm night of everlasting sleep:

There into the hush from which thou cam’st retire.”

Love vs. Death

Sri Aurobindo’s integral philosophy admits “both the claim of the pure Spirit to manifest in us its absolute freedom and the claim of universal Matter to be the mould and condition of our manifestation”. In Savitri, this dual affirmation is symbolised by love, an ideal in whose highest and purest realisation the seeking for ego-transcending spiritual oneness joins hands with an insistence on embodiment. But love cannot be fulfilled in a world ruled by Death, where Matter and Spirit are pitted against each other as the heroine’s antagonist depicts them to be. In order to “vindicate her right to be and love”, Savitri must therefore argue the case for a view that denies Death’s supremacy, yet is consistent with the facts of the real world. This she does by outlining an evolutionary vision which, unsurprisingly, bears a strong resemblance to the theory of spiritual evolution that is at the heart of The Life Divine. It begins with an involution of Spirit in Matter:

“The Mighty Mother her creation wrought,

A huge caprice self-bound by iron laws,

And shut God into an enigmatic world:

She lulled the Omniscient into nescient sleep,

Omnipotence on Inertia’s back she drove,

Trod perfectly with divine unconscious steps

The enormous circle of her wonder-works....

The Eternal’s face was seen through drifts of Time....

Earth’s million roads struggled towards deity.”

Love, like all other potentially divine powers, manifests progressively in such a world, passing through a series of stages marked by a gradual diminution and final disappearance of the limiting and distorting vital ego. Love’s ultimate source, as well as the goal towards which it moves, is that infinite delight of existence which the Upanishads call ānanda. Love, writes Sri Aurobindo in The Synthesis of Yoga, is in its inmost nature and at its highest intensity “the effective power and soul-symbol of bliss-oneness,... at its summits a thing of beauty, sweetness and splendour now to us inconceivable”. To be sure, what we ordinarily refer to as love falls very far short of this description; but that objection poses no fundamental difficulty for an evolutionary philosophy. In reply to Death’s cynicism, Savitri affirms the sublime reality behind the ambiguous appearances of love as we know it:

“Even in all that life and man have marred,

A whisper of divinity still is heard,

A breath is felt from the eternal spheres.

Allowed by Heaven and wonderful to man

A sweet fire-rhythm of passion chants to love.

There is a hope in its wild infinite cry;

It rings with callings from forgotten heights,

And when its strains are hushed to high-winged souls

In their empyrean, its burning breath

Survives beyond, the rapturous core of suns

That flame for ever pure in skies unseen,

A voice of the eternal Ecstasy.”

The spiritual vindication of love is a crucial point in a philosophy that proposes to lay a foundation for the integral transformation of human life. The “whisper of divinity” that redeems love even in its ordinary manifestations reveals the presence of “the imprisoned suprarational”, not only in our higher intellectual, ethical and aesthetic strivings represented by the perennial pursuit of truth, good and beauty, but also in “this great mass of vital energism”. All appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, love in its various forms provides prime examples of “the instinctive reaching out for something divine, absolute and infinite”.

Sri Aurobindo explains in The Human Cycle: “The first mark of the suprarational, when it intervenes to take up any portion of our being, is the growth of absolute ideals.... These ideals of which the poets have sung so persistently, are not a mere glamour and illusion, however the egoisms and discords of our instinctive, infrarational way of living may seem to contradict them. Always crossed by imperfection or opposite vital movements, they are still divine possibilities and can ... become for us, not the poor earthly things they are now, but deep and beautiful and wonderful movements of God in man fulfilling himself in life.”

As the champion of love, Savitri exposes herself, to be sure, to the merciless mockery of her adversary. Death’s barbs have a ring of unanswerable truth to them:

“This angel in thy body thou callst love,

Who shapes his wings from thy emotion’s hues,

In a ferment of thy body has been born

And with the body that housed it it must die.

It is a passion of thy yearning cells,

It is flesh that calls to flesh to serve its lust;

It is thy mind that seeks an answering mind

And dreams awhile that it has found its mate;

It is thy life that asks a human prop

To uphold its weakness lonely in the world....”

But in scoffing at love as an ideal that “never yet was real made”, Death refuses to entertain the possibility that the ideals of the present may be the actualities of the future. As Sri Aurobindo argues in an essay, On Ideals: “Ideals are truths that have not yet effected themselves for man, the realities of a higher plane of existence which have yet to fulfil themselves on this lower plane of life and matter, our present field of operation.... But to the mind which is able to draw back from the flux of force in the material universe,... the ideal present to its inner vision is a greater reality than the changing fact obvious to its outer senses.” Love is just such an ideal, whose ultimate triumph over Death’s negations Savitri has the audacity to predict:

“All our earth starts from mud and ends in sky,

And Love that was once an animal’s desire,

Then a sweet madness in the rapturous heart,

An ardent comradeship in the happy mind,

Becomes a wide spiritual yearning’s space....

Then shall the business fail of Night and Death:

When unity is won, when strife is lost

And all is known and all is clasped by Love

Who would turn back to ignorance and pain?”

Savitri’s victory is a triumph of Spirit over the resistance of Matter, a sign of the power of a life-affirming spirituality to overcome the inertia of the established order and remake our world from within. Death himself, symbol of the eternal “No” that thwarts all our aspirations, proves in the end to be no match for the fiery spirit of the heroine who reveals through her humanity the force of the goddess who dwells in all of us.

Years before Savitri assumed epic proportions, Sri Aurobindo had elaborated a vision of earth’s future, along with the means of realising it, in a series of magisterial prose works including The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga and The Ideal of Human Unity. For his final gift to the world, however, he felt the need to use the heightened mode of expression that poetry offers. Reviving and extending the Vedic conception of the mantra as rhythmic language with a creative power, he sought to make Savitri a force for inner and outer transformation in the lives of its readers.