Auroville – A City for the Future

Book reviewBy Alan

Keywords: New publications, Books, City of the Future, Galaxy model, Auroville history, Auroville Charter, Sri Aurobindo Society (SAS), Environmentalists, Greenbelters, Divisiveness and Development

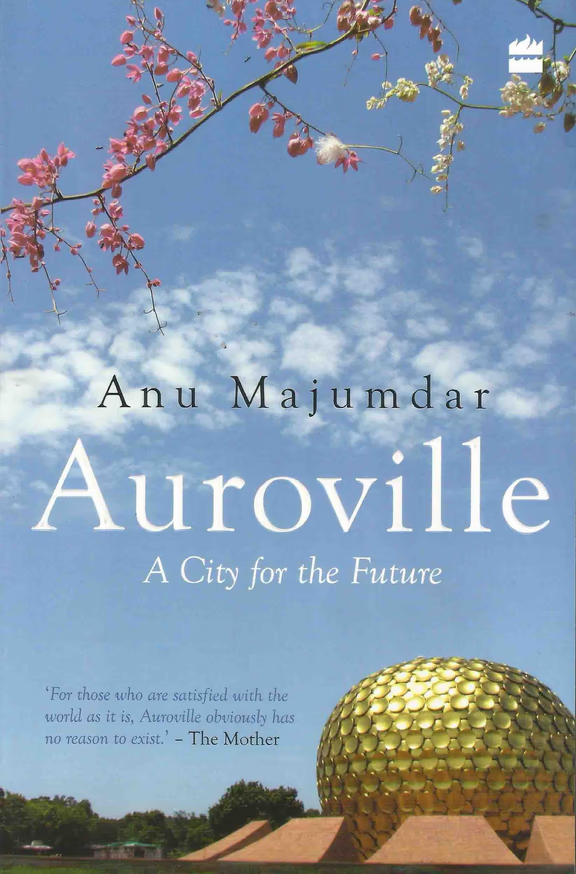

Cover - Auroville, A City for the Future

The first ‘book’ works very well. It is a fine introduction to the history and the main activities of Auroville as well as present challenges. Above all, the spirit of Auroville breathes through the inspiring personal experiences Anu has collected over the many years she has been researching this book. I particularly enjoyed Anu’s own ‘discovery’ story as well as the crucial role played by revelatory dreams in bringing so many people to Auroville.

The second ‘story’ is, for me, more problematic. Not because I am against building the city or exploring the ways in which the Galaxy plan can help us to do this, but because of the approach Anu adopts.

Anu’s stand is clear: the original Galaxy plan, along with the Charter, are the two strands of Auroville’s ‘DNA’: both are essential for its success. By equating the two, Anu implies that the original plan, like the Charter, is unmodifiable and beyond dispute. “In no way can we grant ourselves permission to throw out the Galaxy plan because by doing so we throw Auroville off course and the real potential of the experiment,” she writes.

Anu’s defence of the Galaxy is passionate because she feels it has been unfairly neglected or criticised over the years. This is a fair point. But passions often result in over-simplification. For example, Anu writes that everybody who came to Auroville in the early days came to build the city. This was not the case. She describes the first resistance in the community to building the Galaxy as a reaction to the authoritarianism of the Sri Aurobindo Society. Later, she puts it down to those who wish to turn Auroville into some kind of eco-commune and to live a small, rural, comfortable life. There’s some truth in this, but it is far from being the whole story.

As to what she terms the later neglect of the Galaxy plan, the new generation of architects coming to Auroville in the 1980s contributed to “a full Roger ban. The Mother was found to be clueless, a failed environmentalist and totally out of fashion.” Really?

However, it is the environmentalists and Greenbelters who shoulder the main burden of the blame. Writing about the Greenbelt and those who live in it today, Anu muses, “It almost seems as if it has seceded and has no interest in the city or its overall intention...”

In fact, Anu even accuses “a self-appointed lobby of ‘concerned citizens’” of thwarting Auroville’s development in art and culture. “Art and culture get knocked out by oil and power in some parts of the world, in Auroville by an active environmental lobby”. Really?

None of the above accusations reflects the much more complex reality of Auroville where the views of greenbelters, for example, are as varied as those who live in the city area. (Interestingly, none of her interviewees is working the land, with the exception of Santo who does not talk about his work.) Nor does Anu address the more serious reservations expressed about the original Galaxy plan, including the argument that it takes little or no account of ground topological and social realities.

Anu reports Roger’s 1996 statement that it is the “bad will’ of people who made it impossible to build Mother’s town, but she says nothing about the often inept manner in which some of his supporters have gone about trying to ensure that the original concept was realised.

Nor does she seem to appreciate the larger, complex process of Auroville, even though she quotes Satprem to this effect: “Their delays on the brakes they seem to apply to our motion is part of the fullness of perfection that we seek and which compels us to a greater meticulousness of truth”.

Why does all this matter?

Firstly, because this book is likely to have a wide readership outside Auroville and it will be taken by many of those readers as a factual rather than, at times, rather one-sided version of events.

Secondly, her decision to attack those who question the Galaxy rather than explaining in greater detail why we should adopt it, obscures Anu’s important point that it is time to examine the Galaxy plan with new eyes. Thirdly, it is written in a way that reinforces divisions through employing negative stereotypes of those who question the plan.

Interestingly, in the latter part of the book Anu quotes a number of Aurovilians who are very alive to the dangers of division. “It is time to move beyond this for-and-against trap and find that inclusive third position that helps us move forward, “ says Toine. Anu appears to assent. But does her approach really foster that ‘inclusive third position’?

This somewhat mars an otherwise excellent and deeply-researched book that is well worth reading. Finally, let’s remember Mother’s words that put all our disagreements over the city in perspective.

“This city will be built by what is invisible to you. The men who act as instruments will do so despite themselves...That is why one can laugh.”

Auroville A City for the Future. Anu Majumdar. Harper Collins, 2017.

Available from Wild Seagull bookshop, SABDA and Amazon.in,

price Rs 490.