Ideal cities and Auroville

FeatureBy Alan and Gilles Guigan

Keywords: Cities, Utopias, Ideal cities, China, Renaissance, Industrial Revolution, Urbanisation, Hyderabad, Akhetaton, Egypt, Rebirth, Revue Cosmique, Usteri Lake, Four Zones, Auroville Charter, The Mother on Auroville and History

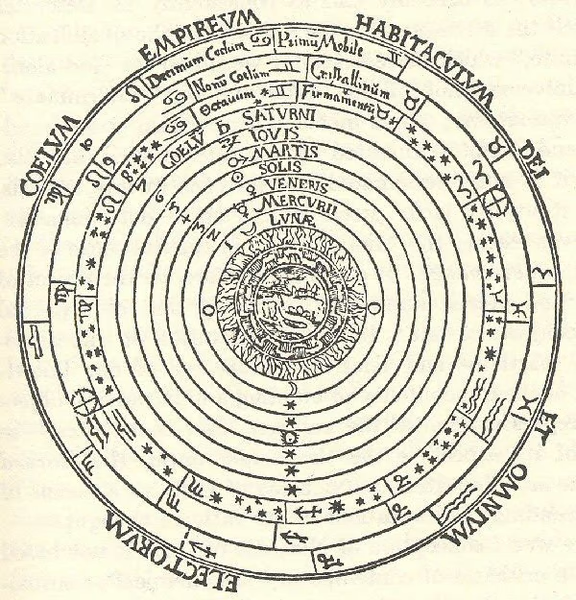

Sketch of layout of The City of the Sun

An idealistic or utopian strand of thought can be found in all cultures. In ancient Indian literature, for example, there is reference to the mythical land of Uttarakuru. “The Peach Blossom Spring” from ancient China describes another utopia. However, these utopias focus upon an ideal society and, in the case of The Peach Blossom Spring, a very rural society, rather than taking the city as the ideal construct. It is only in the Western utopian tradition that the ideal city has received so much attention.

This is because unlike in ancient China, where the Taoist tradition valued nature and natural living above all else, from the time cities arose in the West they were seen as representing the highpoint of the cultures in which they were embedded. It was natural, then, that when people wanted to imagine a more ideal state of affairs, or to critique the society in which they lived, it should take the form of an ideal city.

In around 380 BC Plato described his ideal city in his Republic. Rather than being an architectural treatise, it deals with the ideal relationships between the citizens and defines the nature of the just city-state. Its influence was profound, particularly in the Renaissance when classical learning and culture were being rediscovered in Europe.

In fact, the Renaissance was one of the golden ages of the ideal city concept. This was assisted by the rise of Humanism, which shifted the focus from a divine to a human-centred universe where reason was seen to be the key ordering principle of life.

Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), which literally means ‘nowhere’, does not provide site plans for an ideal city but describes a society in which, among other things, there is no private property, meals are taken in community dining halls and houses are identical and rotated between the citizens every ten years.

Leonardo Da Vinci, on the other hand, was responding to a particular event – a terrible plague in Milan – when he drew up his plans for an ideal city. It included a network of canals (divided between lower canals for tradesmen and upper canals for ‘gentlemen’) and elegant buildings: “Only let that which is good looking be seen on the surface of the city”, he wrote.

In fact, it was believed that, ideally, good government and social order in the state should be mirrored in the appearance and external order of a city. In this context, a series of three 15th century paintings (by unknown artists) called the “Ideal City” are important because they provide a visual addition to the mainly philosophical works of Plato and More. These paintings depict wonderfully harmonious cityscapes of broad squares, colonnades and restrained architectural classicism designed to maximise interactions between the inhabitants and to elevate their thoughts.

The City of the Sun

It is the latter impulse which predominates in the two most famous ideal cities of the Renaissance: The City of the Sun and Christianopolis. The City of the Sun was a treatise written in 1602 by the philosopher Tommaso Campanella while he was in prison. Frances Yates, the English historian describes the city as follows:

The City of the Sun was to be on a hill in the midst of a vast plain. In the centre, and on the summit of the hill, there was a vast temple, of marvelous construction. It was perfectly round, and its great dome was supported on huge columns. The fourfold theme was again dominant. Four main roads led to the centre where there was a circular domed temple.

Inside the vault of the dome was a representation of the stars of heaven and on the altar, which was in the form of a sun, were two globes, one of the earth the other of the celestial skies.

In this ideal city, the citizens possessed nothing; everything was held in common.

Johann Andreae’s concept for Christianopolis was published in 1619. Like The City of the sun, Christianopolis has a temple in the centre, all property is held in common and the layout is symmetrical (The City of the Sun was circular, Christianopolis square).

Campanella and Andreae saw their cities as archetypes of an ideal heavenly and earthly society: both believed the design of their cities would assist in the practical realization of a heaven on earth. In fact, as Gareth Knight points out, Campanella “hoped to establish his city on Earth as herald of a new age.”

The presiding concept behind both these ideal cities was the Heavenly City, New Jerusalem, which, according to the Bible, will descend on earth at the end of the world to usher in the reign of God. (There are interesting analogies here with the Buddhist Shambhala that will descend to conquer dark forces and usher in a Golden Age.) New Jerusalem also has its sacred geometry. According to the Book of Revelation, it is a perfect cube, with twelve foundations and twelve gates.

The Biblical City of God acted as a powerful inspiration for the Puritans colonizing New England in the 17th century. In fact, the Puritans saw themselves as builders of the New Jerusalem on earth.

Later ideal cities

The Industrial Revolution also gave rise to some concepts of an ideal city but this time, largely in response to the terrible conditions of the early industrial townships, it was the social rather than the religious aspect that predominated.

For example, in 1902, social reformer Ebenezer Howard published his treatise Garden Cities of Tomorrow, where he outlined his idea of a planned Social City where people would live in harmony with nature. Welsh reformer, Robert Owen, put his utopian socialist ideals into practice in the design and construction of the village of New Lanark in Scotland for the workers in his cotton mills.

In the early 20th century, French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier had big plans for the ideal city. Architecture, he believed, should be as efficient and simple as the industrial machines that had ushered in the modern age. Inspired by this notion, he planned two modern utopias modeled on this idea of the city as a machine: the Ville Radieuse and the Ville Contemporaine. Both would have massive skyscrapers housing millions of people – rich and poor. Parks and green areas would divide these massive cities into zones of productivity and leisure.

Neither, of course, got built. Nor did Buckminster Fuller’s radical idea to solve overcrowding in cities. His Spherical Tensegrity Atmospheric Research Station, called STARS or Cloud 9s, would be composed of giant geodesic spheres that could float. His floating cities would be anchored to mountains, or left to drift around the world.

Antecedents of Auroville

Is Auroville an ‘ideal city’? Interestingly, when the Sri Aurobindo Society first announced it as a project of the Society in 1964, Mother took only a ‘secondary interest’. However, on 30th March, 1965, she wrote to Roger Anger to thank him for accepting to build her project of an “ideal city”. On 20th June 1965, Huta sent a letter to Mother in which she recounts a vision and some dreams, and then an “old memory” is awakened in Mother and she takes up the project with full enthusiasm. Within three days she has elaborated plans and drawn up the first sketch of the four zones, shown as the petals of a flower. In September, 1965, she issues her first message on Auroville:

Auroville wants to be a universal town where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony, above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities. The purpose of Auroville is to realise human unity.

But what was the “old memory” that was revived in Mother by Huta? Mother said it was “something that had tried to manifest – a creation – when I was very small...and that had again tried to manifest at the very beginning of the century when I was with Theon. Then I had forgotten all about it. And it came back (with that letter): suddenly I had my plan for Auroville.”

Mother also recounts in The Agenda that she had had a plan for an ‘ideal town’ for a long time, but this was in Sri Aurobindo’s lifetime. In this case, she was referring to the possibility of building an ideal township in the State of Hyderabad. This was in 1938. In Mother’s conception, Sri Aurobindo would have been living in the centre, in a house on top of a hill. The town would have been laid out according to Mother’s symbol, delineated with four large petals near the centre and twelve smaller petals around. The town would have been walled, with entrance gates and guards, so that nobody could enter without permission. And within the town there would be no circulation of money.

However, the Hyderabad authorities stipulated one condition that was considered unacceptable: that nothing could leave the State of Hyderabad. Moreover, it seemed highly unlikely that Sri Aurobindo would want to leave Pondicherry. So the plan fell through. (In any case, Mother subsequently told Satprem that she had planned to start materialising the project only 24 years later, which would have been in 1962.)

But it’s possible that Mother was drawing upon an even “older memory” in her new attempt at manifesting an ideal city. And that takes us back to ancient Egypt.

Akhetaton

In 1956, Mother revealed in a conversation that she had been present in ancient Egypt as Queen Tiy (or Tiye). Her son became Amenhotep IV and, seemingly under her influence, initiated a stupendous religious revolution by making the sun god, Aton, the only god to be worshiped.

Georges van Vrekhem in his book, The Mother – The Story of her Life, takes up the story.

“The sun god Aton, never represented in human form but as the sun disk, was central to the theology of Heliopolis, perhaps the most ancient in Egypt, although he played only a minor role in the official religion...Most historians agree that Tiy had an equally strong influence on her son Amenhotep IV. As Berbers and Beumer write: ‘Through his mother Tiy, in this supported by his father Amenhotep III, he must have been initiated in the philosophies around Aton and indoctrinated with the idea that for the religious salvation of Egypt a god like Aton was the only outcome.’ This influence must have been very strong indeed, for after his father had died Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaton, translated variously as ‘he who is faithful to Aton,’ ‘One useful to Aton,’ ‘he who serves Aton’ and ‘reflection of Aton.’ And not only did he change his name, he founded a totally new city, Akhetaton, ‘Horizon of Aton,’ on the right bank of the Nile, halfway between Thebes and Memphis. The name of the city may be understood as the projection of the Sun World into the material world of the earth.

“This splendid city, entirely dedicated to the new creed, was built in an incredibly short time and must have been a costly enterprise. Akhenaton lived there with his wife, the famous Nefertiti (‘the Beautiful has come’) and their six daughters. There he worshiped the sun disk.

“The faceless Aton was declared the only God and the worship of all other gods, of the whole Egyptian pantheon, was abolished. The significance of this act can only be understood if one realizes that the priestly caste was second in power to the Pharaoh – who was a living god, the incarnated Horus on earth – and often vied with him for supremacy.”

In fact, on Akhenaton’s death the priesthood had their revenge when one of Akhenaton’s successors, Haremhab, had the city razed to the ground and all references to Aton were obliterated in Thebes, the centre of the old orthodox religion.

But a formation had been created stronger than bricks and mortar. Van Vrekhem quotes Tanmaya, a teacher in the Ashram school.

“In reply to a question (concerning Akhenaton) I had put her, Mother let it clearly be understood that she had been Queen Tiy, the mother of Akhenaton...She specified that Akhenaton’s revolution was intended to reveal to the people of that time the unity of the Divine and his manifestation. This attempt, the Mother added, was premature, for the human mind was not yet ready for it. It had, however, been undertaken in order to assure the continuity of its existence in the mental plane.”

This is fascinating because it suggests the possibility that others could subsequently access aspects of this formation from this plane. This could explain the undoubted resemblances between Akhetaton – “the horizon of the sun” – Campanella’s City of the Sun, and Auroville – “the city of dawn” (Sri Aurobindo, of course, identified the sun as the symbol of the supramental).

In fact, some Aurovilians have long seen a resemblance between Akhetaton and Auroville. Writing in one of the first issues of Auroville Today, Gilbert Lachaux described Akhenaton’s charter for his city as:

Here is the place that belongs to no prince, to no god.

Nobody owns it.

Here is everybody’s place.

Hearts will be happy in it

But the possible links between historic ideal city concepts go further still. Plato sometimes refers to Solon, the elder Greek lawmaker, who visited Egypt and spent many years learning from the Egyptian priesthood. So it is quite possible that Plato’s influential ideas of an ideal city in the Republic derive partly from Solon and, through him, from the profound occult knowledge of ancient Egypt.

Closer to home

But Mother’s plans for an ideal town may also be discerned in experiments she made much closer to the founding of Auroville.

In the early 1900s, Mother was already writing (in the Revue Cosmique) about the need to found an ideal society in a propitious place on earth. Then, in the 1930s, there was the still-born Hyderabad experiment. She may have been referring to this or to an earlier conception when she said, in 1961, “What I myself have seen was a plan that came complete in all details, but that doesn’t at all conform in spirit and consciousness with what is possible on Earth now, although in its most material manifestation the plan was based on existing terrestrial circumstances. It was the idea of an ideal city, the nucleus of a small ideal country, having only superficial and extremely limited contacts with the old world. One would already have to conceive (it’s possible) of a Power sufficient to be at once a protection against aggression or ill will (this would not be the most difficult protection to provide) and a protection (which can just barely be imagined) against infiltration and admixture.”

Van Vrekhem also mentions a later experiment. He notes that soon after The Mother founded, in December, 1943, the Ashram School she had a very different conception of it from how it subsequently developed. He quotes M.P. Pandit, who remembers: “She said in sum: students from different countries, with their different civilizations and traditions, should be given opportunities to stay in independent blocks; students from France, students from Japan, students from America – each in a separate block not demarcated by walls but by the free development of their own pattern of life, so that if any student wanted to know of the Japanese way of life, he could straightaway walk into the Japanese sector, a distinct part of the hostel, mix with the students there, see what kind of food they ate, how they cooked, how they lived. And at that time she said also that each country must have its own pavilion – a pavilion where its own culture at its highest point should be represented in its special characteristic way... She saw the whole area round the Ashram, with all buildings contained in it, split in twelve different segments together forming the Mother’s symbol.”

Whatever the accuracy of Pandit’s memory, this clearly is the seed of the idea for the cultural pavilions in the International Zone of Auroville.

In 1956, elements of her ideal city concept can be discerned again in a proposal for a film school to be located on a 105 acre site by Usteri Lake. Later the Mother found some notes from that time reminding her to call on one of the two architects of Golconde, Antonin Raymond, to plan the ‘tremendous programme.’

At that time, Mother was developing the Sri Aurobindo International University Centre (as it was then called) and the film school was supposed to be part of it. In fact, the “tremendous programme” included not only a film school but also the construction of residences for an international community of at least 400 people, a model township for local semi-skilled and unskilled employees, and a “wide buffer belt” of farms, orchards and gardens. The international township would include, among other things, a non-sectarian temple for worship; recreation areas for swimming and other sports; playgrounds for children; indoor recreation and dining halls; community administration offices; health facilities; schools; a cinema; a shopping centre; water works; and an electric power plant.

In the end, the project did not happen because the money to buy the land did not come and the American film-maker, Dr. Alexander Markey, who was a key person in the project left and, subsequently, died.

Later, Mother commented to Satprem about the project, “That’s what happens – things change. It’s not that the project stops, but it’s forced to take other paths.” Those “other paths” surely included, eight years later, the founding of Auroville.

The echoes are unmissable. Mother called the failed Lake project, ‘New Horizon’ (surely a reference to Akhetaton) and gave a message:

New Horizon will open the way for mankind to a new and truer life.

A decade later, in her welcoming message at Auroville’s Inauguration Ceremony, Mother said:

Are invited to Auroville all those who … aspire for a truer and higher life.

Auroville, then, can be seen as the latest link in a chain of ideal cities stretching back thousands of years. Like many of the ideal ‘social’ cities, the plan of Auroville was intended to maximise harmonious relationships between residents (interestingly, Roger Anger, the architect, kept a print of one of the Renaissance “Ideal City” paintings in his house). Like the ideal ‘sacred’ cities, Auroville has a yantric dimension which unites earth and heaven through sacred geometry, numerology (the four zones, the twelve gardens of Matrimandir etc.) and symbolism.

At the same time, it is very different. Unlike those earlier experiments, Mother emphasised that Auroville would succeed; it would be manifested in its true form. “Even if you don’t believe it, even if all the circumstances seem quiet ... It may take a hundred years, it may take a thousand years, but Auroville will be because it is DECREED.” And at another time she explained, “You say that Auroville is a dream. Yes, it is a “dream” of the Lord and generally these “dreams” turn out to be true – much more true than the human so-called realities!”

Auroville, she wrote in its Charter, “will be the place of an unending education, of constant progress”. Is this why Auroville is the ‘city of dawn’, of beginnings? And is this why, unlike the rigid geometric forms that enclose ideal cities like The City of the Sun and Christianopolis, the spiral arms of the Galaxy seem to be endlessly reaching out for new experiences, new forms of consciousness?