Winds of Change

An interview with JorgeBy Anusha

Keywords: Technology, 3D printing, Open source design, Renewable energy, Centre for Scientific Research (CSR), Auroville Earth Institute (AVEI), Svaram, Wind turbines, Terrasoul farm, Globalization, Makerspace, Fab Cities and Fabrication Laboratory (Fab Lab)

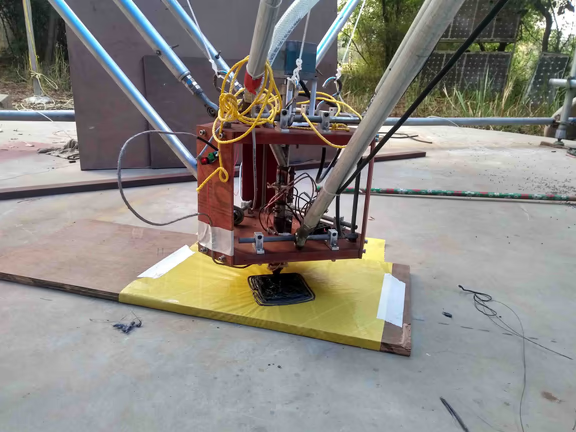

Precision building in three dimensions - the printer in action

Auroville Today: When did you come to Auroville? Tell us about your initial years here.

Jorge: When I first came to Auroville 9 years ago, I worked at CSR and at the Earth Institute.

I had been living and practicing yoga in Tiruvannamalai before that and Auroville had attracted me as a place where I could practice karma yoga. The need to work had become stronger and stronger in my meditations, and eventually I decided to move here.

When I first joined the Earth Institute, I had wanted to train and work as a mason but Satprem did not agree. He thought I would not survive the heat and I think he was right! Instead, as I had an engineering background, he requested that I build machines for Earth Institute.

Sometime later Juan from Terrasoul asked me if I would help him build the farm. That’s when I transitioned to living and working at Terrasoul to create the infrastructure for the farm. I built houses for volunteers and continue to do infrastructure projects and repairs at the farm.

How did you start building wind turbines?

My interest in wind turbines began in Ecuador with mechanical water pumps. There I also learned to design, build and install small hydropower turbines and slowly got involved in rural electrification projects. I spent some time with Jan Imhoff who was building wind turbines at CSR. Eventually I began building an open-source wind turbine design. In fact, I built my first wooden blades at SVARAM, where they make musical instruments – they had the space and the tools in their workshop!

Essentially, the project of building wind turbines was born out of a curiosity and a local need. Several people in Auroville were using solar energy for electricity in their homes. And at certain times of the year their battery banks would get drained. During the monsoon, for example, the production of energy goes down to about 15% of what we usually have. I would hear several people complaining about having no power supply during the monsoon.

So I started exploring wind turbines as a renewable energy source that could complement solar power. In Auroville, I recommend hybrid systems that use both solar and wind energy as we don’t have the ideal wind conditions for producing electricity. We have gentle winds that are good for running mechanical water pumps. Electrical windmills, on the other hand, need higher average wind speeds.

One of the first people to install a wind turbine in Auroville was Martanda. He wanted to increase power production at his farm and I suggested that he add wind energy to his combination. This proved to be a successful experiment.

You have been working in rural India spreading this technology over the last years.

I have worked in the renewable energy field for 15 years in different parts of the world. In Ecuador, where I come from, I was involved in a project of electrifying villages in the Amazon Basin with small hydro power systems. Here in India, my specialty continues to be rural development. I feel that this is my calling – helping rural people in remote areas where no services reach. There are approximately 300 million unelectrified people in India. They also tend to be the poorest communities.

I work in the spirit of the Open Source movement. When I built these small wind turbines, they were Open Source design. I wasn’t the designer of the machines. The original design was by Hugh Piggot, a Scotsman who published a booklet with his wind turbine design which has become the most popular Open Source design built around the world. This design has been modified and expanded by innovators around the world over many years. Through Open Source, designs and the instructions of how to build turbines are available to anyone today.

How does Open Source impact your work in rural areas?

For one, we don’t have a factory that builds wind turbines. Instead we have training programmes that train people to use open source platforms so that they can build the machines themselves and do so at a fraction of the cost of a company manufactured turbine. The Open Source movement enables a farmer or village mechanic to build a wind turbine on his own. He does not need to be an engineer for this. He only needs interest and curiosity.

We want people in remote areas not only to be self-sufficient in energy but also in manufacturing and maintaining their own energy generating equipment. Currently, we’re creating a national network of local entrepreneurs, mechanics and individuals who can do this. Having local technical support systems for renewable energy is essential for its success.

Where have these projects been implemented?

We have been running training projects in areas around Pune, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. These areas have a very good wind resource with significant energy needs. Trainings have been done in Technical Institutes, Ashrams, farms and students have included farmers, electricians, university students, entrepreneurs. All these trainings are done through the Centre for Scientific Research (CSR) which has been a strong supporter of this initiative. A key training centre has been the National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE) based in Chennai, which is now building a small wind turbine Makerspace with our technical advice.

The concept of Open Source sounds like it has democratised manufacturing. How does it work?

The spirit of Open Source design is that you make available any intellectual development to the world to use by publishing it on the internet. This means that if you have written a book or built an object or resolved a technical problem, you publish it under a number of different websites. Others, then, have the possibility of building a copy of what you published. Often, they modify it to meet their specific needs. And in some cases, the changes are significant improvements on the original design. The result is that you have a global network of individuals helping you to improve and upgrade your design. Windempowerment is one such open source group that specialises in wind energy and its productive applications.

Open Source has made it possible for anyone, anywhere in the world, to access all the information they need in order to build something themselves. On websites such as thinginverse.com, you can literally search for anything, download the design and build it free of charge. And this is the point of Open Source. Instead of protecting your intellectual pursuits and trademarking them, you want what you have created and offered to the world to evolve into something else. This global sharing of ideas through Open Source has enabled us to reimagine our world and our cities.

You spoke about Fab Cities at your presentation on Makerspace last month. What is a Fab City?

The Open Source movement, along with the development of Makerspace, has evolved into a larger pursuit of a Fab City.

The city, as it has evolved in the last century, has become a massive consumer of materials and producer of waste and carbon emissions. The Fab City project seeks to reverse this trend by imagining cities as centres of local production so that people, through their inventiveness and resourcefulness, are able to manufacture the products they need within the city itself. Not only should we be able to make everything ourselves, we should also make it Open Source so that others can benefit. The Fab City concept is based on the vision of a global flow of knowledge and communication to support local production so as to make cities environmentally sustainable, affordable and self-sufficient.

The Fab City project is a global collaboration. Cities like Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Shanghai and the state of Kerala are members of this network.

The idea of Fab Cities goes against the flow of globalisation. Globalisation, in economic terms, implies that you build at the place where you can get the biggest amount of production for the least cost. And then you ship it all over the world. In this paradigm we lose a lot. We are reduced to clients, rather than enablers and makers. I believe that retaining and exercising the capacity to make is important. I believe this is a spiritual process also, it is karma yoga.

Do you think that Auroville already has some of the attributes of a Fab City?

Yes, Auroville is a good example. We started as a community, in a place with nothing but just barren land. The second blessing was that there was no money. The pioneers were forced to do as much as they could with as few resources as possible, which continues to this day. Auroville has carried forward that spirit of empowering those who make and do, those who are creative. We are doing many of the things that are aligned with the principles of Fab City, though not in an organised way with the rest of the world.

You have a Makerspace here in Auroville. What is this?

A Makerspace or a Fabrication Laboratory (Fab Lab), as it’s known in some parts of the world, is a space to make, to build. It could be a mechanic’s shop, a class room or a kitchen, but with one distinction – a Fab Lab uses advanced technologies in the form of digital technology, computer controlled machinery that make precision in manufacturing possible. A 3D printer enables us to manufacture objects or components that are impossible to create using traditional methods.

Let’s take ceramics as an example. Several potters in Auroville create beautiful, functional objects. In spite of the availability of clay and people who understand the material, however, we cannot make ceramic ball bearings or a ceramic toilet because a toilet has complex parts that require precision manufacturing. However, if we could 3D print these parts, then, with the right kind of clay and firing ovens, we could build our own design of low flow toilets instead of buying toilets that consume large volumes of water.

Digital technologies are important because they bridge the gap between what is typically a cottage or small industry run in a traditional way and the big manufacturer who makes precision parts with advanced technologies. The implications of this are tremendous! They have democratised manufacturing, making it possible for individuals to produce anything they want at an affordable price. I’ve visited factories in people’s kitchens and living rooms where they’re making extremely complex parts at a fraction of the cost of what they would buy in the market. This is the new industrial revolution. It’s called Fabrication 2.0. In combination with open source, this has revolutionised the possibilities of innovation and production in fields as diverse as health, energy, housing, fashion and the arts.

What have you been building at the Makerspace here?

First of all, we have built open source 3D printers. This has taken 2 years and a lot of experimenting and fine tuning. Now we have the largest 3D printer in the country. We also built a computer-controlled mill that works by chipping away at wood and light metals.

The work that we’re doing currently at the Fab Lab here is in ceramics. We want to design ovens, roof tiles, flooring, toilets. We are also experimenting with recycled plastics. This is proving to be quite challenging as the quality of plastics can vary quite a lot. Nevertheless, we are trying to recycle PET and Polyethylene bags.

The 3D printer has taken our wind turbine project to the next level. Now, a farmer or village mechanic can build a CNC or 3D printer following Open Source designs, which enables him to automate the fabrication of blades while doing the other things he has to do. And this is a universal machine that can produce parts for other things – parts of chairs, flooring, tiles.

We want to start training young people in Auroville in 3D modeling on a computer. Digital technologies are the basis of Makerspaces and we need people who are familiar with these technologies in order to innovate. We also want to invite creative people, artists, to collaborate with us in order to experiment with materials and develop new ideas. If we want to build a house solely from local materials, for example, we need people who are willing to drop many conventional notions of design and think differently.

Our goal in the not too distant future is to 3D print affordable housing in Auroville. This is important if we are to grow this township. Having more people will have a multiplier effect. Not only will we need more houses, we will need more working spaces, more facilities, more equipment and furniture in schools. And if enough people follow the philosophy of the Fab City, produce and buy locally, we have multiple benefits of creating more jobs, controlling our carbon footprint, reducing toxic waste and enjoying objects that suit our specific conditions. We, in Auroville, already do this in a number of ways. We produce our own furniture, food, cheese and paper, amongst other things. The beauty of Auroville is that we are partially already in this flow.

What would Auroville need to do to join the Fab City network?

Joining the network would require a community decision and a commitment from the governing body. The big benefit of joining the network is that then we would start linking with other Fab cities and projects around the globe. We would share our projects with them and vice versa. This would connect Auroville globally; it could be the next step for us.

In the meantime, we are exploring ways of building networks to reach and train more people in wind energy. In Nov/Dec we are organizing the largest small wind turbine conference that brings together 15 open-source trainers from around the world with a specialty in building small wind turbines by hand or using advanced manufacturing processes. NIWE is funding 80 global participants that can come for one month to be trained. If they come from developing countries they will be fully funded by NIWE and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The conference will be held in Chennai and we will spend 10 days building equipment and 4 days in conference proceedings. Several Aurovilians and volunteers will be participating in this event. We expect around 300 global and Indian participants at this event which is co-sponsored by Windempowerment, a UK NGO that also promotes open source wind turbines.