The story of cashew told on film

FeatureBy Lesley

Keywords: Films, Documentaries, Aurora’s Eye Films, Outreach Media, Women’s issues, Farmers, Pesticides, Organic biopesticides, Healthy Cashew Network and Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS)

1

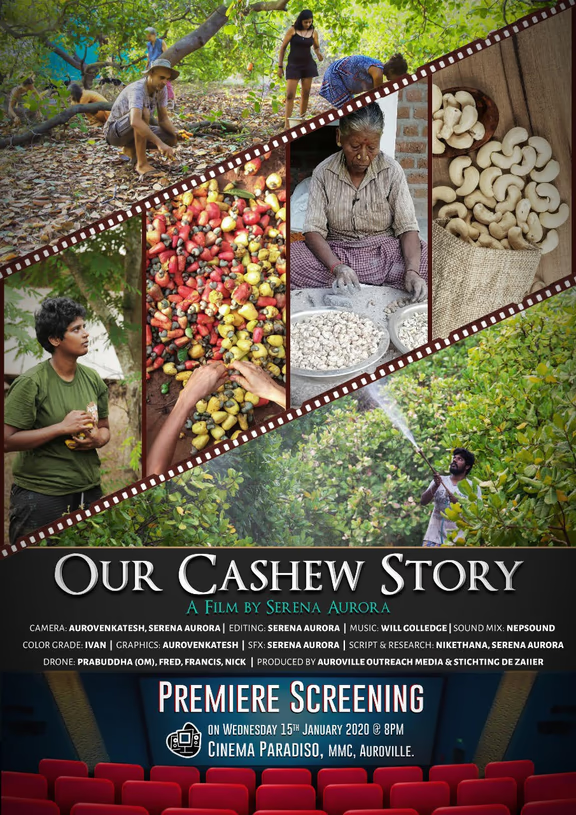

Her 42 minute documentary, Our Cashew Story, was recently launched in Auroville. “This is my journey into discovering our cashew story, like investigative journalism, but also a personal journey,” says Serena, about her efforts to tap into the “wealth of knowledge and 50 years of experience” on this favoured crop in the region. Her Tamil colleague, Aurovenkatesh from Auroville’s Outreach Media, assisted her in the making of the film, and contributed his Tamil viewpoint to “balance” her opinions, so that she didn’t “get lost in the western mind set”.

As various articles over the years in Auroville Today have highlighted, Auroville’s land is interspersed with privately-owned cashew fields, on which farmers often spray toxic pesticides. These pesticides have a detrimental effect on the health of villagers, farmers and Aurovilians, and yet the practice continues, despite Auroville’s efforts to encourage farmers to switch to organic pesticides.

In her film, Serena uses the innovative narrative device of an old-fashioned TV in order to present the different voices in the cashew debate. This includes government advertisements for pesticides, as well as news reports that portray deaths, widespread mental retardation and other devastating health effects in the neighbouring state of Kerala, that were directly linked to the now-banned pesticide Endosulfan. “The TV also represents how we sit back and watch something go by, and we get stuck in a voyeur perspective,” says Serena. “I put a bowl of cashews next to the TV set, to show we’re playing a role as consumers. The background is moving, to suggest: Where are we? Where is our stance? Even a vegan in the UK plays a role, because veganism uses a lot of cashews, and that impacts cashew production here.”

Serena and Aurovenkatesh were tenacious enough to convince farmers and pesticide sprayers to participate in the film – an inclusion of a voice that is often omitted in the debates on cashews. “Aurovenkatesh had the contacts, he knew who to speak with, so it’s all thanks to him,” says Serena.

Local farmers are not ignorant of the toxic effects of pesticides, says Serena. “”They know it’s poison. [Aurovilian] Rita describes how a local farmer’s cow drank some pesticide and died. People drink it to commit suicide, so they know it’s bad. The story of the Endosulfan deaths in Kerala was big, so I think they know about that.”

In the film, one cashew farmer, Anandham, describes how, after spraying, “this intense burning sensation starts – the pain is indescribable. It lasts all night.” Cashew sprayer Ezumalai describes how sprayers become “dizzy and faint” and “appetite decreases”. The two doctors featured in the film – Auroville’s Dr Lucas and Dr Kurien Thomas from PIMS Hospital – point to the serious effects of pesticide inhalation by sprayers (fluid accumulation in the lungs, paralysis etc.), as well as the chronic effects of passive inhalation in the general population, such as breathing difficulties.

Farmer Anandham states that he and other farmers are aware of the effects, but have “no choice”, because the cashew yield will be smaller if they do not use pesticides, and profits will therefore be less. In general, local farmers, harvesters and sprayers do not make much profit from cashew crops.

So, given the small profits and the terrible health effects, why do farmers continue to spray toxic pesticides?

“I think it’s multiple things,” says Serena. “Word of mouth recommendations and easy access to pesticides. The government pushes pesticides to farmers, and because farmers hear something from a voice of authority, they believe it. So there are all these pressures. They’re stuck in a system. They feel powerless, and they not able to change. If you are in that situation, what else can you do? You do what people tell you to do, to get the money, feed your family. It’s just survival, compliance.”

The film connects local cashew production practices to the global trade of cashews, suggesting that it’s big business when it’s done at scale, and contributes significantly to India’s economy. But Serena points out how opaque the big business and trade is. “From the farmer to the processor to the exporter, there’s huge gaps in the research. The pattern I see, with any product, is the farmer gets the worst deal. They do the hardest work and have the smallest voice.”

The film highlights one local Tamil farmer who converted to organic biopesticides, and began diversifying into other crops, such as lemons and chillis. Diversity of crops is essential to ensure the abundance of insects and animals life – which has decreased significantly in the locality, because of the shift to the monoculture of cashew crops. While this farmer’s yield has generally been better, he understands there is a risk factor and that some years he may get a smaller yield. “Even if he gets a bag less of cashews, he’s OK because he knows his soil is doing well and he has peace of mind,” says Serena. “This farmer says he doesn’t like people spraying near his farm, and he wants people to see his story and convert. So this is a way to move out of the pattern, and the village can gain the benefits.”

Serena’s film articulates all the initiatives and efforts that Auroville has put into this issue over the decades, including those by Dr Lucas, Rita and Nyal, and the current initiative: Auroville’s Healthy Cashew Network. While she praises these initiatives, she points out that none of these efforts have been sustained over the decades. “It’s like a relay race, where a Aurovilian holds the baton and fights the fight – to educate farmers, do a test plot. And then for some reason, the baton is dropped and someone else takes it up. This has happened over years in Auroville. Now the Healthy Cashew Network is holding the baton, but it’s a small group and people are so busy. So I invite the audience at the end of the film to become a member of the Healthy Cashew Network so that the baton won’t be dropped.”

Serena points out that the north-east Indian state of Sikkim has converted fully to organic agriculture, and that Auroville should aim to assist the neighbouring farmers to do the same. She points out that Tamil farmers previously used to use neem, before “the brainwashing” began. “It’s not a completely lost knowledge, but it’s becoming lost. The new generations are forgetting, so we need to re-build trust.

“That’s one reason why Auroville is here. We’re trying to be a conscious community, look after ourselves, the environment and people around us, and yet we’re surrounded by toxic clouds for a few months a year. It’s crazy, when you think of it! We’ve made a forest from a desert, but we’re breathing toxic air! We can have an impact, but one or two people can’t do it. We need to all be in it together.”

Serena proposes some other measures. The first is that Auroville should take more responsibility to consume only organic cashews. This would include stocking only organic cashews in its shops (PTPS currently sells non-organic as well as organic cashews in its store). Auroville could also create a market for farmers by buying all the cashews cultivated in the neighbouring areas, on condition that they are not sprayed. Serena concedes that this approach has been tried by Aurovilians in the past, and made a loss. “This takes manpower, policing, relationships to be built, and it comes down to hours, and everyone is too busy.” Aurovilians could also join in the harvesting of cashews. Overall, she points to the need to support local farmers and to localise processing. “If everywhere in the world localises production, it will give farmers a voice.”

An extensive bioregion outreach dissemination strategy is planned for the film, and Serena has created a Tamil version for local audiences, in the hope that this “very local story” will appeal to them. She plans to screen it in neighbouring villages and schools in the coming months, followed by a discussion facilitated by members of the Healthy Cashew Network. The film will not be on YouTube for the near future, as the team wants to focus on public screenings. “My purpose is to bring people to watch it in a room, and talk about it,” says Serena. The important part is the conversation after the film.” She also hopes that Tamil TV stations will take it up, as well as universities and political groups.

She points to one possible breakthrough on the horizon: the KVK, a section of the agricultural ministry in India that advises farmers on spraying, are starting to promote ARKA natural insect repellent made by Faborg, an eco-business near Auroville. “This is one huge step,” says Serena, pointing out that farmers listen to such voices of authority. While the KVK will possibly continue to simultaneously promote toxic pesticides, this step forward is “amazing,” says Serena.

“The ball is rolling,” she says. “The push is starting to gain strength again. My dream is for people to watch the film and share ideas of how we can come out of this.”