Towards an integrated water management strategy for the bioregion

Editorial — By Alan

Keywords: Water management, Bioregion, Vilappuram, Cuddalore, PondyCAN - Pondy Citizen's Action Network, Auroville Town Development Council (ATDC) / L’Avenir d’Auroville, Farmers, Village relations, Groundwater monitoring, Saltwater intrusion and Pondicherry Groundwater Act

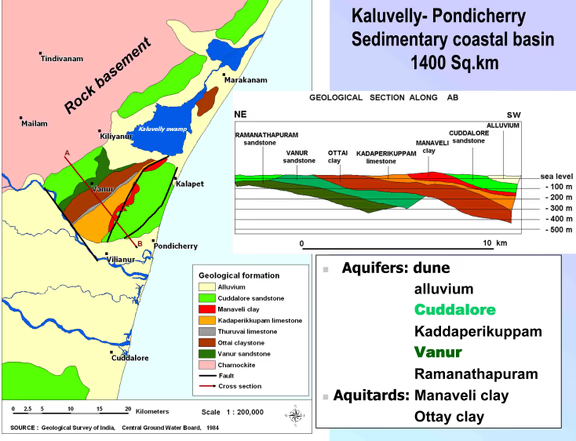

Map of the immediate bioregion of Auroville

The bioregion was defined as Pondicherry, Auroville, and the surrounding districts of Villupuram and Cuddalore (PAVC), an area of 2500 sq. kilometres that constitutes a distinct ecological bioregion along the Coromandel Coast.

The purpose of the meeting, organized jointly by the U.S. Consulate, Chennai, PondyCAN, The French Institute and TDC L’Avenir, Auroville, was to bring together people working on water and environmental issues to work on an integrated management programme for the region’s water resources.

Unfortunately, representatives of the Puducherry Government could not attend as the Puducherry Assembly was in session. Nevertheless, some interesting presentations gave valuable insights into both the nature of the challenges and the possible solutions.

The challenges

Water quality and water tables are dropping all over India, and Pondicherry State is no exception. Mr. V. Radhakrishnan, Hydro-geologist from the State Ground Water Unit, pointed out that the per capita availability of water in the State dropped from 1960 litres per person in 1901 to 600 litres per person in 1991, and it is projected to be only 224 litres per person in 2020.

In 1973, groundwater resources in Pondicherry State were still defined as ‘prolific’, but in 2013 they were classified as ‘over-exploited’. Between 2000 – 2010, the levels of all the aquifers dropped by between 5 – 14 metres, and salt water has intruded into the coastal aquifer system, in some places as far as 4 kilometres inland.

Why? The reasons include encroachment and neglect of water bodies due to rapid urban expansion; over-extraction due to the vast number of tube wells and cheap or free electricity for farmers; and decreasing ground water recharge due to the conversion of agricultural lands for residential, commercial and industrial use.

There are also failures of governance. Historically, the water bodies in Pondicherry State were looked after by Syndicates Agricoles, an elected body of local farmers. But this successful system was allowed to decay and now water is centrally managed. This, along with tube well technology that allows many people to have their own wells, gives little incentive for local people to take care of their community water bodies.

Moreover, current practices of planning and development are localized and compartmentalized, failing to take into account the impacts on the environment, people and associated livelihoods, and different government departments have different priorities that influence how water is managed. Even when there are promising government schemes, for example to assist farmers to shift to less water-thirsty crops or to renovate irrigation ponds, the bureaucracy involved is often daunting and so the farmers often do not take them up.

The linking of water and energy

Shifting to a global scale, Dr. Jennifer Turner from the China Environment Forum of the Woodrow Wilson Center, pointed out that it is crucial that water is included in industrial development scenarios. She argued that not enough attention is paid to the big picture of how water and energy are linked, and she illustrated this with reference to modern China.

Water scarcity is the biggest problem China faces today: 30% of the water available is of low quality, and 300 million Chinese have difficulty accessing clean water. Yet a massive proportion of China’s water, some 20%, goes to the coal sector to produce goods primarily for export. (Incidentally, 68% of China’s pollution is due to the burning of coal).

The primacy of coal in China’s energy mix, and the shortage of water in the area of the coalfields means that China is planning a massive project to transfer water from the southern, more rain-fed part of the country, to the arid north, with all the associated losses.

The concern is that India wants to go the same way as China by developing its coal resources to produce more energy. (In this context, it is rumoured that a new coal-fired plant is planned for Marakanam, to the north of Auroville.) This will definitely impact its water reserves as well as increase air, soil and water pollution.

However, perhaps the biggest challenge worldwide is that water – a precious, finite and irreplaceable resource – is taken for granted by so many people, and this leads to a culture of apathy. As the introduction paper to the meeting put it, there is a need for a “paradigm shift in protecting and conserving water”, for which we need to have “shifts in individual and collective values and norms, structure, policies and laws.”

A case study

How do local farmers view the water issue? Audrey Richard-Ferroudji and colleagues of the French Institute made a study of Sorapet, a village in Pondicherry State. They noted the decline in the use of irrigation tanks compared to individual tube wells, and a trend for the farmers to grow more casuarina and paddy, which are water-thirsty crops, because of labour and market issues. Figures show that the number of tube wells continues to increase, and they are dug at greater depth now because there is less water in the shallower aquifers. But the main concern for the farmers is not water – there is little use of drip-irrigation, for example – but the difficulty of getting farm labour and a decent price for their crops.

The farmers want more mechanisation and higher profits. However, the fact that few young people are willing to take up farming makes the farmers very pessimistic about the future of farming in this area. The statistics bear this out. In 1991, 16% of the villagers were cultivators. In 2011, this proportion had dropped to 2%.

Possible solutions

The consultation meeting not only focussed upon the challenges. It also indicated some possible solutions. Mr. V. Radhakrishnan, the Pondicherry hydro-geologist, listed out some of the initiatives taken by his department (the Department of Agriculture) to improve water resources in the region. They include constructing check-dams across watercourses to improve groundwater potential; digging recharge shafts in riverbeds and renovating wells to recharge the aquifers; desilting village ponds and communal water bodies; and educating farmers in how to adopt water conservation measures and shift to low water-consuming crops.

He also noted that in 2004 the Pondicherry Groundwater Act had been passed to regulate groundwater extraction in the State, and that construction of rainwater harvesting systems was now mandatory in all government buildings.

Tom from the Town Development Council, Auroville, felt it is crucial that the government gives new importance to the protection of existing water bodies, and that the coastal regulations that prohibit certain activities taking place close to the coastline in order to prevent pollution and seawater intrusion need to be strengthened and applied consistently.

But how to overcome pervasive apathy and educate the general public about the importance of water conservation? In this context, Auralice Graft’s presentation on the ‘Seeds of Change’ programme might offer one solution. Auralice, an Aurovilian who works with PondyCAN, has been working in local schools to encourage what she terms ‘proactive citizenship’. The programme helps students conduct environmental audits, neighbourhood projects and promotes the awareness of the importance of wetlands. Although the programme has not been running very long, she has already seen changes in attitudes and behaviour.

The consultation meeting ended with the participants breaking up into three groups to focus, respectively, on data collection, the institutional changes needed for more effective water management in the bioregion, and on designing a campaign to build awareness leading to results-based action.

Conclusion

It is always difficult to assess the effectiveness of such meetings. The defined purpose was to bring together people working on water and environmental issues to work on an integrated management programme for the region’s water resources. This didn’t really happen, partly because of the absence of key players like officials of the local administration.

Moreover, when like-minded people come together they often over-emphasise the importance of such meetings because they celebrate the feeling that they are no longer alone. And, as Nini of PondyCAN wryly pointed out, even apparently successful meetings do not always translate into action.

One reason this happens is that such meetings often do not deal with the real challenges. In the case of this meeting, a great deal of useful general information was imparted, but the crucial challenges are often in the details that tend to be neglected. For example, how do you integrate traditional farming practices with new, water-saving technologies? How do you deal with status quoism or apathy in the official structures set up to deal with water issues? And how do you reprogramme people’s belief that progress equals abundance and the abundant use of resources? For activists often forget that many good ideas founder on the rock of human psychology and self-interest.

At the same time, the importance of such meetings often lies in the ‘unquantifiables’ – the meetings over coffee leading to new alliances or joint programmes, the moving personal human story that inspires new hope, the sudden discovery of the human face of bureaucracy etc.

Moreover, in the case of topics like managing scarce water resources, it is crucial that somebody keeps the issue alive, keeps trying to light the blue touch-paper that, one day, will ignite purposeful collective action. In this respect, meetings like this are both important and worthwhile.