Ray Meeker’s “Fire and Ice”

FeatureBy Lara

Keywords: Exhibitions, Ceramics, Centre d’Art, Sculptors and Golden Bridge Pottery

.jpg

Fifty years ago, Ray Meeker was a student of Peter Voulkos, an American ceramic artist as much known for the large scale of his works as for the way in which his massive hands parted and joined clay. Peter was most often seen throwing bowls on a wheel that scarcely a man could handle alone. I witnessed this myself as an undergrad at the New York State College of Ceramics: large groups of students and faculty crowded around the pottery studio, witnessing this unique and somewhat crude dance of man and clay.

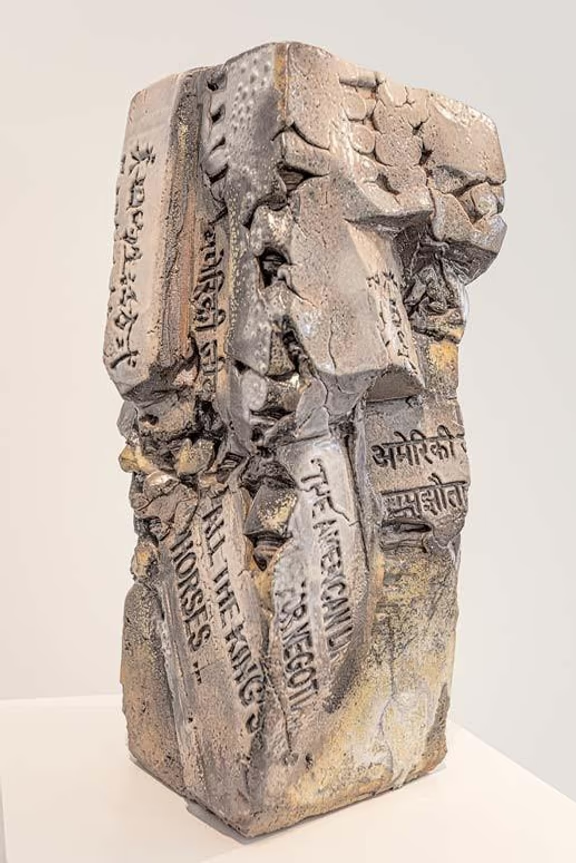

Ray is similarly a figure in the ceramics world known for the physical performance of the grand scale of clay. Ray’s work is so large scale that it’s like figurative sculpture – rough bodies of stamped and parted clay. One might say that his work and his personality are wrapped together in an enigma similar to Voulkos’. And yet Ray is a singularly modest man, with work and style characterized by a removal of personal ego.

Ray was also influenced in his early work by the fired clay houses of Nader Khalili, who scaled the common ceramic vessel up to the size of the inhabitable space. Thus Ray’s work commonly jumped the scales from vessel, to figure, to building, firing for days until temperatures were high enough to vitrify the cross section of walls. In many respects, Ray’s accomplishments in fired houses have surpassed that of Khalili. Only a few years ago, his widow Iliona Outram Khalili came all the way to India to see this legacy of Nader’s work. Though only a few examples still stand in Auroville and the Pondicherry region, the local area is still the best gallery of this kind of work.

Ray is a craftsman’s craftsman, cutting out excess words like a huge slab of cleaved clay. The thinkers love his work because it is true and sensuous material expression, rife with a million metaphors – and yet it evades simplistic language. Two dimensional words fail to capture the spirit of discovery in his work. Even for the most experienced writers, the fragments of text imprinted in his sculpture seem to speak more clearly than any summary.

With his wife Deborah, at Golden Bridge Pottery in Pondicherry, Ray has been a teacher of generations of ceramicists in India, an initiator of a massive movement of modern Indian ceramics. Many Auroville potters and ceramicists have entered the Indian ceramics world on account of their experiences at Golden Bridge.

And yet – after nearly fifty years – this was Ray’s first exhibition in Auroville... a long overdue welcome. Ray is no longer creating his fired houses, as he did in the pioneering years in Auroville. But the exhibition “Fire and Ice” bears witness to his lifetime body of work – cross-continental shaping of the earth as by giants; the search for beauty in raw form, the imprinting of language and memory, the transformation of clay by firing.

Each of his pieces in “Fire and Ice” has personality and idiosyncrasy as if they are portraits, or individual figures. As far as I can see, “Fire and Ice” is a testament to human resilience – that endured through the extremes of exposure that makes us what we are. Beauty may be found in each twist of fate, or obscure detail – and no material is to be discarded. The gesture of the clay holds the imprint of the master’s mood and action (quite like the work of Voulkos). Scrutiny of the apparently ugly reject-piece reveals exquisite textures from its formative processes. Such is the whim of the master craftsman; in creation and destruction. It makes us question if there can be such a thing as a mistake in the hands of the maker, when each accident becomes a means of further creation. Every action – cleaving, pressing, molding, firing, glazing, firing – has an evidently clear intention. It is as though the artist is the witness of the self-realization of the clay.

And for every piece, the risk is calculated and close to the surface. Solid clay will explode in the kiln, and the larger the piece, the greater the risk. But these works have just the right hollowing out to withstand the forces of firing. For me, it is this delicate balance between creation and destruction – so technically mastered in Ray’s entire body of work – that is so evocative on a conceptual level:

“Fire and Ice” refers to a short poem by Robert Frost, which queries if the world will be destroyed by the former or by the latter. Dominique Jacques writes evocatively about this post-apocalyptic nature of his work in the exhibition’s frontis statement; monuments of a cataclysm, indexes of the earth’s destruction now so fitting in age of rampant, post-industrial, global capitalism and global climate change. Some may see this work as an allegory of the earth’s imminent destruction, an index of humanity surviving through apocalypse. But I see Ray Meeker’s search for beauty at the end of the world.