Planning for the wider bioregion: Auroville- Pondicherry-Villupuram-Cuddalore

An interview with Probir, Lalit and AravindaBy Alan

Keywords: Regional planning / bioregional planning, Puducherry / Pondicherry, PondyCAN - Pondy Citizen's Action Network, Lt. Governor of Pondicherry, Government of Tamil Nadu, Auroville and its bioregion, Health, Education, Environment, Water management, Bioregion, History, Vilappuram, Cuddalore, Reports, Economy and Maps

1

An important meeting in terms of planning for the larger bioregion took place on 11th September in Pondicherry. Hosted by Citizen’s Action Network, PondyCAN and the Puducherry Planning Authority, with participation of civil society from all the sub-regions, the consultation meeting was also addressed by Lt. Governor Dr Kiran Bedi, Chief Minister V. Narayanasamy, The Puducherry Chief Secretary Ashwani Kumar and the Principal Secretary of the Tamil Nadu Government.

Auroville Today asked three of the organisers to assess the significance of the meeting and to talk about the challenges and successes of bioregional planning in this area. Probir is the President of PondyCAN, Lalit is an Aurovilian planner who worked for many years with L’Avenir d’Auroville, and Aravinda is an environmentalist and member of the Auroville Highway Task Force.

1

What is the difference between bioregional planning and conventional planning?

Lalit: The main drive in conventional regional planning is managing growth in rural areas and facilitating urbanisation. Unlike bioregional planning, it does not place much emphasis on supporting ecosystems.

Probir: Conventional planning does not look at the whole: no importance is given to health, education, the natural environment and so on. Moreover, town and country planning are totally segregated and sufficient attention is not given to the countryside. In bioregional planning we want to break this dichotomy and emphasise a rural-urban continuum where the rural areas are seen as the more important aspect because without them the towns cannot be sustained.

Secondly, conventional planning is confined to political boundaries: states do not participate in each other’s development. But when it comes to shared issues like water or coastal erosion, sticking to state boundaries makes no sense. Bioregional planning is defined by environmental and cultural factors, not state borders.

The other problem with conventional planning is that it is typically a top-down approach. The government will conceive of a project and implement it without hardly any consultation with the people affected. This is why many such projects fail. Bioregional planning places great emphasis upon consulting with those who will be affected by planning decisions in their area, because they often know much better than the planners what should be done.

Bioregional planning consists of three layers. One is the spatial foundation which is the natural features, water, minerals, crops, fauna. Then there is the infrastructure of human settlements. Finally, you have the superstructure which is the various activities.

The built component has to be harmonised with the natural environment because we are dependent on ecosystem services and human activities can have hugely negative impacts on the environment. Unless we understand the impact of nature upon society it is difficult to plan.

On what basis did you define the Pondicherry-Villupuram-Auroville-Cuddalore area as a distinct bioregion?

Probir: Water is the key thing, so we looked at shared watersheds. There are also many linkages between the various sub-regions – historical, cultural, trade, etc. On a personal note, when we were young, we used to cycle to places like Auroville, Kaliveli and Bahour Lake near Cuddalore so this also represents the larger space where we feel at home.

How new is the concept of bioregional planning in this area?

Probir: We started the Citizen’s Action Network, PondyCAN, in 2007 but it was only in 2008 that we got into bioregional planning. The trigger was the Pondicherry port. It was causing erosion for kilometres up the coast in the neighbouring state of Tamil Nadu, so we thought how can we just work on Pondicherry?

With the port, we saw that the government had planned something and people only came to know about it too late when it was being implemented. Initially we campaigned against it and made protests. But then we got smart. We collected a lot of information and based on that information we began lobbying the local government and the Central Government in New Delhi. We also used the media and went to court whenever necessary.

But it was always a struggle because the project was already being implemented. So we thought, why don’t we involve ourselves in bioregional planning to avoid this kind of thing happening in future?

Yet the concept of bioregional planning has not really taken off yet. Why has it taken so long to acquire traction?

Probir: The shift from thinking about one’s own area to the larger bioregion is challenging. How to accept that you need to get involved in something that is happening in Cuddalore 30 kilometres away? But if you realise that what is happening 30 kilometres away could destroy your water system, you realise that you need to expand your awareness and your sphere of activity.

Lalit: Regional planning forces you to stretch beyond your own space. In Auroville we have not reached that larger consciousness. For example, within the Auroville Master Plan area of the greenbelt there are six villages, yet their growth needs and aspirations are not known to us. Also, bioregional planning requires a very different level of effort from local planning and we have not yet reached that level.

Over the years it has been only a minority of Aurovilians who have been involved in bioregional outreach. Does bioregional action not suffer from the sense that we are not here for that?

Lalit: It’s true, I think this has been holding us back. At the same time, in the early years our first task was to take care of the land. We didn’t have the capacity to do more. Yet, through initiatives like Village Action, we created a lot of goodwill locally and from this level, the next stage will evolve. Now I think the threat of the new highway has been the trigger. From now onwards, I think Auroville will be very serious about the bioregion.

Aravinda: Yet the early Aurovilians were intimately connected with the bioregion. The original foresters went out to the bioregion to get seeds for Auroville. And we realised very early on that to work on our watertable meant that we had to work on the whole thing, the watershed of our bioregion.

Probir: But for a bioregional consciousness to develop in the wider population there has to be a tipping point when a sufficient number of people are actually thinking and doing something about it in each of the sub-regions of our larger bioregion. Until that happens it will not take a form.

Was the recent meeting in Pondicherry in any sense a tipping point?

Probir: Perhaps it was. This was the first time we brought together people from the entire bioregion who had been actively working in their own spheres. When they heard what others were doing and the challenges they were facing, people realised that this is a huge support group that can help them in their own work. There was a strong empathy because people recognised there were so many common challenges, like water, of course, which is the biggest challenge for everyone.

If I am fighting my own battles and thinking I am the only one doing it, I don’t know how long I will go on, but when I see all these other people fighting similar battles, there is a sense of reassurance that I am on the right path.

Aravinda: For me there was a strong feeling of togetherness and solidarity and a sense that, yes, it is going to happen, now is the time.

What about inter-state cooperation? If the two neighbouring states do not fully cooperate, a lot of the key work in the bioregion will not get done. Are you more hopeful now that this will happen?

Probir: It was very important that not only the Lieutenant-Governor but also the Principal Secretary of the Tamil Nadu government and the Chief Secretary of Pondicherry were at the meeting, and that they committed themselves to working together on bioregional issues. Also, the fact that the Chief Minister of Pondicherry said he was going to meet the Union Minister in Delhi and tell him that Pondicherry would be taking up bioregional planning is a huge step. This is the first time I’ve heard him say that.

If we can get an okay from the Union Minister, then we have made the first step in the political process.

At the bureaucratic level, inter-state cooperation on bioregional planning will only happen when there is a policy that the Tamil Nadu Government and Pondicherry Government will work together. After this meeting I am hopeful we are closer to getting this.

However, we as civil society can move and work everywhere; we are not tied to state boundaries. We can talk to the Central Government as well as local farmers and fishermen and we can keep coordinating the work of bioregional planning at our level. It is important we keep strengthening the base for bioregional action.

The Principal Secretary of the Chennai Government mentioned that it was important that the people on the ground and the government find ways of working together. But aren’t we talking about very different mindsets? The government is used to working top-down while the bioregional planning you are engaged in seems rooted in participatory decision-making.

Lalit: You’re absolutely right. By taking up these activities, you are taking on the entire political and governance system, which is a big task. So we have to be smart. While we need to educate the political class in a different way, there is a whole range of government schemes – for sanitation, education, afforestation etc. – which can be tapped into for bioregional development.

Probir: I think the top-down approach is not okay but the bottom-up approach is not always okay because wherever there is ego we have huge problems. So now we talk about the ‘inside out’ approach where you base yourself upon shared values like environmental and social justice, dignity, compassion, transparency and accountability. In Auroville these values are built in, but outside you have to work upon inculcating them.

What is PondyCAN’s experience of working with government agencies?

Probir: Over the years of activism we have worked very closely with the Public Works Department (PWD) of the Pondicherry Municipality. Earlier we would just go and warm chairs in the corridors; they wouldn’t even look at us. But now they respect us because they know we will go to Delhi, or take them to court, or go to the media to expose any wrongdoings.

Actually, they need us because they know that they don’t know how to do their job well: the expertise often lies with the local people who will be affected by their schemes. But as they don’t have access to them, we become the channel of communication with these people.

So while we have had a bit of a love-hate relationship with the PWD, now the ground is laid and they listen to us. In fact, collaborating on the Bahour project with them has been a joyride so far.

Bahour is an area on the southern border of Pondicherry State. It is very rich in history and has the second largest lake in Pondicherry, home to migratory birds. However, it has been very much neglected by government agencies.

While there is all this talk in India at present about ‘smart cities’, we framed Bahour as a ‘smart village’ project. We took the Lieutenant-Governor there and explained this to her and she loved the idea.

What we have managed to do here is to bring all the government departments, experts and civil society organisations round the same table to decide things together. The idea is to put all the government schemes on the table and see how we can tweak them to fulfil the needs of the people living there. Of course, some local priorities are not covered by any scheme so we have to find a way of including them. The bottom line is that everything has to be based on a shared vision and there has to be collaborative planning. Each government department has its own scheme but if someone objects, they either drop it or work together to modify it.

In the past, correct implementation of projects has been an issue, but now the contract for the work has been given to the community itself rather than to outside contractors, as happened under the old system. And the people themselves are taking photos of the work being done and circulating them on our WhatsApp group, so everybody knows what is happening.

Interesting things have happened in the process. The Pondicherry Government is bankrupt, so we decided to raise funds for the work through the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programme. A lot of local companies have now come forward.

Over the last couple of months we have achieved a lot. Now all the tanks have been desilted and we are working with the Tourism Minister to develop alternative forms of tourism in the area, like fishing and agritourism.

So PondyCAN has been a catalyst in this process?

Probir: In Bahour there is a strong group of committed individuals but for the last ten years they had been voiceless because nobody listened to them. What we are doing is just empowering those people. They know what they have to do, they can do it, we are just giving them support and building bridges between them and the government. Now they go to meet the PWD Chief Engineer on their own and speak to him on equal terms whereas earlier they were scared to do this.

We are putting all these efforts into Bahour because we thought if we can successfully build a relationship with the government departments there, this can be a model for other areas of our bioregion.

Lalit: It’s all about successful energy mobilization. Today we have a supportive Lieutenant-Governor and a group like PondyCAN which is taking it as a full-time job to engage with the different players: it’s their energy which is making it work.

Probir: You need activists. The government will not move on its own. The people have to push it to get things done.

What role do you see Auroville playing in this?

Aravinda: I feel very strongly that Auroville’s involvement with the bioregion is a necessity. In fact, it has no other choice. I feel what was given to us in our Charter, the ideal of human unity, has now become a need everywhere for climate change etc. is forcing humanity towards this need for oneness.

But human unity is not just an ideal. It is also a ground reality and Auroville has to start peeling off the layers which have isolated it in the past from its neighbours. For there are wonderful energies outside and we choke ourselves by limiting ourselves to one small area.

Probir: Auroville already plays a key role because, unlike the other areas of this bioregion, you started from scratch and created your own bioregion. So, in terms of the experience that you have gained, you are very important. What Auroville has done in terms of water conservation and biodiversity represent the shining stars of this bioregion and people come here to be inspired, to learn how it can be done. And when people are inspired, they go back and do something.

Lalit: For 50 years Auroville has been like a nursery for seedlings, now the wider plantation has to start. Auroville has the institutional and intellectual capacity to play a leading role in sustainable bioregional planning. Now it has to step up.

Probir: What is important is to identify people who are passionate. It’s not about planning or planting trees. We need people to take the wheel. We need drivers from Auroville who can push this forward.

Box 1: History of bioregional planning in this area

Sept 1986 – Letter from Joint Secretary, Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD) to Chief Secretary, Pondicherry to take up Interstate Regional Planning.

21st Dec 2004 – Reminder letter from MoUD for the formation of Working Group for Regional planning.

15th May 2008– Consultation meet in Auroville “Water management through Integrated Planning and Regional Collaboration”.

25th July 2008 – Meeting held at the Chennai Secretariat with all the Secretaries by Dr Harjit Singh Anand, Secy HUPA

26th July 2008 – Meeting at the Pondicherry Chief Secretariat on “Preparation of Regional Plan” attended by Secretary Urban Development, TN.

4th Oct 2008 – Presentation to His Excellency the Lt Governor of Pondicherry Shri Govind Singh Gurjar at Rajnivas.

5th Oct 2008 – Presentation to Chief Minister in his chamber. Others present – LAD Minister, Chief Secretary, other Secretaries and Heads of depts.

Feb 2009 – “Sustainable Regions Collaborative Planning” a 3 day participatory workshop by JTP, Germany held in Auroville, inaugurated by the Lt Governor of Pondicherry.

24th July 2009 – Meeting held in the chamber of Chief Minister, Pondicherry regarding preparation of Interstate Regional Plan.

31st Aug 2009 – Letter from Govt of Pondicherry to Prof KT Ravindran requesting him to prepare a concept plan for the Interstate Regional Plan.

11th Feb 2010 – Brainstorming session organised by TCPO, New Delhi for the 5 southern states in Auroville on Regional Planning.

8th Oct 2010 – Meeting at French Consulate on Bioregional Planning along with officials from TCPD Pondicherry.

30th Oct 2010 – Meeting with Chief Secretary regarding the Pilot Project on Regional Planning funded by ADEME.

15th Feb 2012 – Completion of Report – “Sustainable Regional Planning Framework for Pondy-Villupuram-Auroville-Cuddalore”.

24th Mar 2015 – Meeting with TDC at Auroville to discuss “Bioregional Water Action Program”.

5th May 2015 – Consultation meeting in association with US Consulate “Water Stewardship for the Sustainable Development of the Bioregion”.

2016 – Formation of the alliance “All for Water for All” with representatives from the entire bioregion.

2nd Feb 2016 – (World Wetlands day) to 23rd Mar (World Water Day) – Water Festival for 50 days covering the entire bioregion.

11th September 2018. Consultation meeting on PVAC bioregion in Pondicherry.

BOX 2: Extracts from Report on Sustainable Regional Planning Framework for Puducherry, Villappuram, Auroville & Cuddalore (PondyCAN, Feb. 2012)

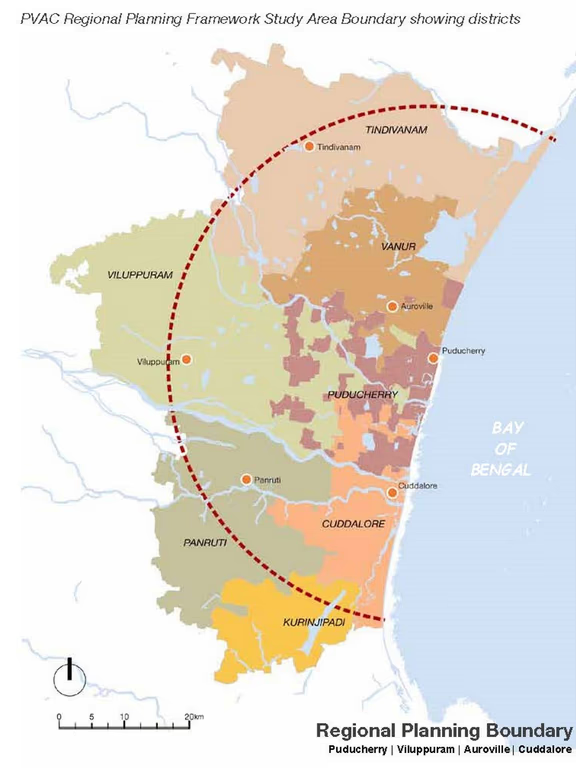

The Puducherry – Viluppuram – Auroville – Cuddalore (PVAC) Sustainable Regional Planning Framework is an initiative to establish an integrated inter-state growth strategy for Puducherry and its neighbouring districts in the state of Tamil Nadu – Viluppuram and Cuddalore. The preliminary analysis and recommendations are organized within four key themes – Land Use, Transportation, Water, and Energy. Other themes will be addressed as part of ongoing efforts at various local, sub-regional, district or regional levels as funding opportunities arise in the future.

Key challenges in the bioregion

Land

While Puducherry suffers a tremendous strain on its urban infrastructure and quality of life because of uncontrolled and unplanned expansion and excessive development cramped into a limited land area, the immediate vicinity in both Cuddalore and Viluppuram districts have vast tracts of land languishing from paucity of investment. Other critical concerns related to land use include: unplanned sprawling growth, lack of enforcement, loss in agricultural land, and minimal forest cover and recreation areas.

Mobility

The region is characterized by limited sustainable transportation choices that provide connectivity between the urban centres, towns, and rural areas. Traffic congestion, lack of dedicated pedestrian/ bicycle facilities, safety, poor quality bus service, absence of a regional airport, and multiple port developments are some of the other major concerns related to efficient movement of people and goods.

Food security

A significant portion of area under cultivation in the region is rapidly being converted into non-agricultural uses. The challenge is to protect the agricultural land base and to encourage its active use for food production. Also, the productivity of the current agricultural land in the region is poor owing to unsustainable practices, lack of sufficient infrastructure and loss of agricultural labourers.

Water

In the region, water tables are rapidly declining and its quality deteriorating, with saline intrusion affecting aquifers along the entire coastal region. Crucial, irreplaceable water bodies continue to be threatened by industrial and residential expansion.

Environment

Natural resources are under severe strain because neither their use, nor plans for their protection, conservation, and augmentation are coordinated among the stakeholders within the region.

Infrastructure

One of the biggest challenges faced in the region is the accessibility to physical and social infrastructure, especially in the rural areas. Due to this inaccessibility to both physical and social infrastructure in rural areas, there is migration towards the urban areas thereby adding tremendous stress on the existing infrastructure.

Livelihoods

Puducherry has one of the highest per capita income levels in the nation and it is ironically surrounding by some of the poorest districts of Tamil Nadu. From a macro-level perspective, the region’s economic disparities and imbalances are a reflection of contemporary India’s growth.

Heritage

The region is extremely rich with architectural and cultural heritage that dates back hundreds and thousands of years. Rural and urban heritage sites, cultural practices and local traditions in the entire region are under threat of development and economic pressures warranting an urgent need for a comprehensive heritage preservation strategy with government support.

Governance

While our region’s units of government are numerous, in order for the concept of integrated planning to materialize, there should be more collaboration between governmental agencies at all levels. At the same time, the participation of the community is a crucial part of any democracy. Both the government and the citizens need to be enabled and empowered to make any governance work.

Recommendations

Land

Urban Growth boundary. The concept essentially involves demarcating a boundary around an existing growth centre to curtail unplanned or uncontrolled conversion of agricultural lands and open spaces by developers in search of cheaper land.

The concept of designating an urban growth boundary relies heavily on the success of developing compact “complete communities” that support higher densities for a diverse mix of uses with adequate infrastructure, easily accessed through multimodal transportation facilities.

Integrated Rural Ecosystem Greenways. As a buffer to the development and human activities, between the designated urban growth boundaries, connecting greenbelt areas may be identified that serve as buffers and linkages between the growth centres.

Transportation

Paradigm shift required. It is imperative for the PVAC region to make a paradigm shift towards planning its transportation model.

Densely populated regions, if planned appropriately, have smaller carbon footprints per person than less dense areas, which tend to involve higher travel times and thereby higher consumption of energy.

East Coast Road development.

Development along the East Coast road needs to be controlled to allow only low-intensity, environmentally-friendly development for various reasons including the fact that the ground water levels along the coast cannot meet up to the demand created by such increasing development. New development can be located along The NH45 as a new corridor for development by upgrading it to accommodate high speed transportation systems such as Electric Multiple Units (EMU) or the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system.

Promote public transport. Make policy changes that incentivize a shift from being car-centric to more public transport driven mobility by adopting Transit Oriented Development (TOD) as a preferred model of development.

Provide high speed transit to connect all the growth centres in the PVAC region.

Promote electric vehicles. Introduce subsidies and incentives for the use of electric vehicles and alternative renewable sources of energy.

Promote walking and cycling across the region by providing pedestrian and cycling facilities or bicycle expressways.

Water

Reduce groundwater extraction. The water budget will stay negative even if all the tanks of the district are rehabilitated. It appears therefore urgent to reduce the amount of groundwater extracted for irrigation.

Improve collaborative water management in the region.

Encourage sustainable water usage for farming and promote organic farming for water saving techniques.

Contain urban water demand. Minimum charge on electricity or introduce a cap on the number of electricity units and water consumed per year.

Introduce ground water metering. Restrict use of bore wells to one season.

Subsidize water harvesting equipment and compulsory provision of rain water harvesting for individual houses.

Water User Associations to manage tanks. Tanks to be managed (rehabilitation, operation and maintenance) should be exclusively done by the Water User Association (WUA) only.

Energy

Promote long term renewable energy plans at the regional level.