Ever slow green: an interview with Christoph Pohl

An interview withBy Valentina

Keywords: Documentaries, Afforestation, Auroville Film Festival, Education, Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest (TDEF), Forest Group, Aunusya forest, Bliss forest and Brainfever Media Productions

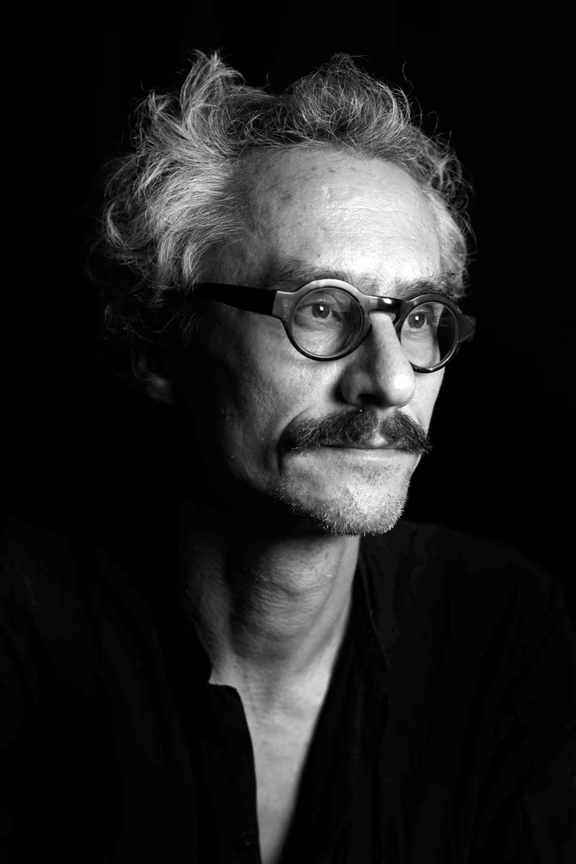

Christoph Pohl

A still from the film: a klte flies over the dense Auroville forests

Auroville Today: What was the main idea and motivation behind your film?

One of the aspects of Auroville that impressed me most when I first came was its forests. I could hardly believe it when I learnt that all these forests were created from scratch and that Auroville was a barren desert plateau when it started in 1968. So I became interested in forestry, I started living in a forest community and also started to volunteer in forest work, which for me offered a great balance for my media work mostly sitting in front of a computer. Being involved in filmmaking and media on the one hand and forestry on the other, it naturally led to the idea of making a film about Auroville’s forests. Making a feature-length film had also been a dream of mine for a long time, as it probably is for any filmmaker, feature-length being the king’s discipline of filmmaking. And the basic concept for Ever Slow Green was born. I created a project proposal that I submitted to the 50th anniversary team for funding. My main ambition was to create a film with a cinematic aesthetic. I didn’t have a fixed script but I had specific ideas supporting my vision, for example, the constant use of slow motion emulating the slow pace of the forest.

Was the film conceived as a way of helping protect Auroville’s forest?

This is not a fundraising video, which would be much shorter, but a documentary film telling a story. Nonetheless, if I manage to sell the film, 30% of all income will be donated to the Forest Group.

The film aims to share with the world the story of this unique re-afforestation project. It is very difficult to replicate this experiment in any other place. It’s not only about people planting trees, but the community aspect is essential. People live here and love the forest because they have grown with it. It is mentioned in the film that what makes it unique is its longevity. In other reforestation projects, people usually have a limited time to execute tasks and after the job is finished, they go, so there’s no community left. That’s not the case for Auroville’s forest. One of the things that I wanted to get across is the forester’s deep-seated passion for their creation. But even with this uniqueness, Auroville’s forest is still very vulnerable to outside threats, like the proposed highway that created a lot of stress within the community. So my hope is that the film can also get to people who understand the value of the work that has been done here.

How was the film financed?

The project proposal to the 50th anniversary team was eventually approved but only for a quarter of the amount asked for, so I had to put in a significant amount on my own as well. Technically, this is a ‘no-budget film’ (less than 25,000 Euros). It has only been possible because all crew members liked the project and gave their time and energy without being paid their normal fees.

What were the main challenges that you faced in making the film?

Because of the reduced budget, I had to cut down the shooting time. Originally, I planned to shoot over one year so I could capture the different looks of the forest through the seasons, but that was impossible with the new budget. Finally we shot everything within four months (from September 2018 until January 2019), five to six days per month (27 days in total), during the monsoon season and in winter, when the forest is lush and most vibrant after the rains. The weather brought up some technical difficulties: on some early mornings, the lenses would fog up from inside, so we couldn’t shoot and we had to wait until they dried up. From the creative point of view, the most challenging thing was to play many different roles at the same time. I was producer, director, editor, and I also recorded the audio interviews on my own. So this game of ‘wearing different hats’ was very tricky. For example, as a director I couldn’t always concentrate on the creative part of the film because as a producer I had to deal with the financial and organisational elements of the shooting at the same time. Also the mindset of an editor is really different. Preferably the editor watches the footage on the computer for the first time and has no attachments to particular shots or characters, like, for example, not knowing how difficult it was to get a certain shot.

Making a film about a community from within that community has advantages and disadvantages. I had access to places and people that an outside filmmaker would not have had so easily. On the other hand, I could not always make entirely creative decisions because I was also personally attached to certain footage.

What about the editing process?

From the beginning I was clear that I wanted the audio to lead the storytelling and not to have any ‘talking heads’ in the film; all interviews are off-camera. So the college of voices is the main skeleton of the film, and then I intuitively added the visual footage on top later. I was looking for intimate personal experiences of people in relationship with the forest. My main criteria was to find in the voices that particular quality that comes when you speak from the heart. I interviewed 17 foresters which gave me 14 hours of audio interviews to sort out. My associate producer, Lesley Branagan, was instrumental in helping build a structure and putting the story together. In that way the film doesn’t necessarily have a traditional dramatic arc (the rising of a conflict until a climax, and then the resolution), but it’s more like a book with different chapters flowing in a free way. I also wanted to break the direct correlation between what is seen and what is said, so the film has more layers of communication. I had to navigate 26 hours of video material. At some point I had the feeling that I didn’t have enough action, there was too much walking, but I ended up sorting it out.

The main soundtrack is taken from the album “Curling Pond Woods” (2004) by North American musician Greg Davis. I really like the slow pace of the music and it came to my mind when I decided on the rhythm of the film. Not knowing him personally, I contacted Greg by email and he liked the concept of the film and agreed to a minimal fee and royalty contract. Additional music was composed by Aurovilian friend and sound artist Chloé Sanchez especially for the film. She is also responsible for all the bird sound recordings, which she recorded in Auroville.

What would you say is the best thing about the film?

I think you can really feel each forester’s love for the forest. There is also a quality of ‘things that can be read between the lines’, what is being said is not all that is being communicated.

What are the future plans for the film?

I have just started submitting the film to various film festivals worldwide. One purpose of sending a film to festivals is to find a distributor who can help to sell it. This is the world of the film industry which I’m not familiar with. I am currently looking for some additional funds to have a professional colour correction done, as I did what I could with help from photographer Marco Saroldi, but it needs improvement. Also some funds are needed to make a DCP (Digital Cinema Package), which is the format that is required for screenings at many film festivals and in cinema theatres.

Festivals require submitted films not to be published yet, so it will take at least another year before it becomes available on the internet. After the festival rotation, the film will surely be distributed to all AVI centres, schools and institutions for environmental education inside India and abroad.

For more information visit www.brainfever.in/ever-slow-green