Change in Auroville

An interview with Jocelyn, Min, Gijs, Jaya and DaveBy Alan

Keywords: Library of Things (ALOT), Lockdown, Economy, Governance, Pour Tous (early years), Solar Kitchen, Auroville history, Personal history, Foodlink, Farm Group, Integral Sustainability Platform (ISP), Auroville Health Fund and 50th Anniversary – Auroville

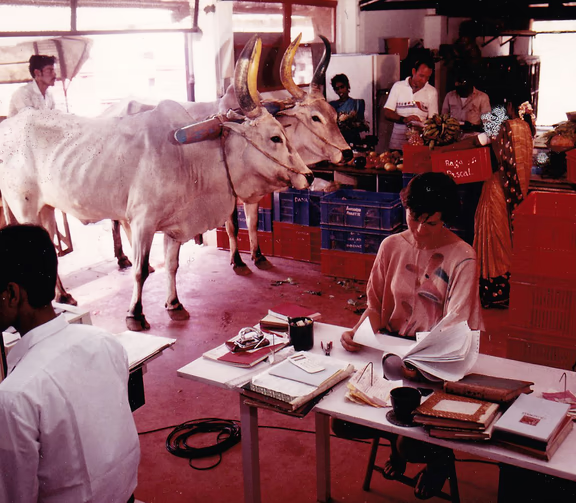

Early Pour Tous

Many view the disruption caused by the lockdown in Auroville as an opportunity to radically transform our economy, governance, food provision systems etc. and a number of proposals to achieve this have already been made.

However, we know very little about how change happens in Auroville because we have not documented how previous attempts have fared. Consequently, while it can be argued that what was relevant yesterday may not apply today, can we learn from previous successes and failures?

Auroville Today brought together some change-makers to discuss this. While only some aspects of this complex issue are touched upon in this discussion, and some may disagree with the perspectives expressed, we hope it will stimulate further exploration.

Auroville Today: What are the major changes that have happened in Auroville over the years which have not been externally imposed?

Jocelyn: The creation of Pour Tous in the 1970s and the Solar Kitchen in the 1990s are important ones.

Jaya: One of the major changes in the 80s was with the maintenance system, which shifted from collective sharing to the present more individualistic system. Though the intention was to take care of everyone, long term it created a very unequal system – the opposite of its intention.

Gijs: The participatory process to select members of working groups was an important attempt a few years ago to make the process more transparent, organized and accessible.

Dave: For me what has changed is there are so many of us now, it is getting difficult to represent ourselves directly, so we are struggling to find a system to choose people who can genuinely represent us.

Min: Since 2005, which is when I came, I have observed more privatisation of interests. Today, for example, there is hardly anywhere in Auroville experimenting with collective facilities.

I see this as a trend but I don’t know what causes it. In terms of work, a lot of us look outside for action now because not much is going on in Auroville.

And yet, over the years, there have been many ideas for change. Some have succeeded, many others have failed. Why? What makes for success?

Jaya: When Gilles created the Solar Kitchen initially he had practically zero support: the popular opinion was that nobody wanted to use collective kitchens any more. But within months more than 700 people were eating there because it served varied food with care, and provided a social environment where people could meet spontaneously, something which had been missing.

Dave: There are things that create and things that slow momentum. I have a tag line for Auroville which is, if you have an idea, do it yourself. If something is going to happen, it needs people who are going to push it through with tenacity, and be willing to stick it out and work through even the boring bits. Somebody needs to be doing the work, this is much more important than the talkers.

Jocelyn: A new initiative may begin with an individual, but it can’t be sustained by just one person because they will get overwhelmed. Building a strong group is very important to the success or failure of a new initiative. I’ve been involved in a number of change initiatives, including the Free Store, Pour Tous Distribution Centre, Creativity and Santé, and all are still functioning because of their teams which provide a solid foundation.

Jaya: Teamwork is very important. Shivaya and I carried the Unity Pavilion project initially, and we did a huge work. But I realised that while I’m good at starting things up because I have the drive and tenacity, I’m not a top manager or organiser for the detailed daily running. So with the continuous increase in activities, we’ve been focusing on getting a larger team to run the project. When people come to work at Unity Pavilion, they often find it messy because there’s a lot of freedom. They sign up for a work that needs to be done but at the same time we want each one to find their way and expression. So we try to create a space for growth, flexibility and creativity. This can be challenging but it is amazing what comes out, how people grow and widen.

These days the first generation of Aurovilians really has to look at succession and contingency planning. This is why we want to become dispensable in the day to day work, while being assured that everybody is aligned with the vision and that there is a collective intention to realize it.

Dave: For me it’s a lot about personal leadership. Inspired managers lead through example. They behave in a way which comes from their own deepest sense of self. This is quite rare in Auroville. So how can we allow those people to develop?

The hard graft part is also part of personal leadership, pushing yourself when the going is difficult or boring. Often, when the excitement has worn off, the spark goes out and then you lose people who were really excited about it at the beginning. So how can you keep people inspired?

Min: I tend to work with people who are relatively new because I’ve already made assumptions about the people who’ve been here longer. I also find they are less available because they are already into something. So if I want to do something new, I look for people who are willing to take risks and are not jaded or jarred by what happened before.

Jaya: Having researched and worked with the Mother’s symbol as represented at the Matrimandir, it became very clear that whenever your work involves people, you have to have some form of organisation. Mother defined certain qualities as relating to humanity and when you see where they are located in the petals, these qualities are all on the Mahasaraswati axis. And Saraswati is organization as rhythm, music, mathematics, precision and harmony, not rigidity and bureaucracy.

Gijs: It would be useful if we all learned more about organizations. For me, what is important is the different levels of scale and different cultures of collectivity, individuality etc. Also, I see any

organisation as a living entity. It is born, goes through different life cycles, and, at a certain point, dies. If we see it evolving like this, it could make for greater flexibility.

Jocelyn: What interests me is how people know when they should start something new. I have a particular way of knowing. It starts in my body, which begins vibrating differently, then synchronicities happen and the energy starts building. Then I don’t have to do anything; I just have to follow it. If you force an idea, it doesn’t work.

Dave: For me it is always decided by the people I enjoy working with.

So what about all the good ideas that went nowhere? Why did this happen?

Jocelyn: I’m sure there are a lot of really good ideas that came from the Retreat but they remained ideas because we didn’t have the people to take them forward. Mother said we need organisers, but we don’t pay enough attention to this.

Jaya: We had some absolutely outstanding selection processes. Then the original concept of the participatory selection process began to fall apart because, to my mind, we didn’t have facilitators that understood the process and could hold it when outcomes did not follow the normal political ways. At the same time, it was not possible to fully avoid manipulation. When the working groups became involved it did not work as the process was intended to function independently. So you need to keep certain processes outside the working groups if you really want change to happen as the bureaucracy has never been a mover of change.

Jocelyn: I tried to create the Auroville guard with Aurovilians only. For the first year it was successful but after a year people from an outside agency were employed to do the patrolling. If I had been more involved it might have been different – I could have handled the inevitable blips that happen. So you’ve really got to be present if you want to drive change.

Jaya: Shyama and I took up the first running of the Solar Kitchen. We wanted to source local food, so we offered to take what our farms could produce. We had a regular menu but for each item we had maybe ten recipes, so there was always variety. But when we left, that vision got lost. The food is still good and cooked with care, but there is less variety, and no catering to individual needs.

Dave: When John died, I didn’t have the motivation to keep going with Foodlink because it was his thing. It could have been carried forward by others, but that didn’t happen. It was the same thing with the Farm Group. There was a plan and it was working okay as long as John and I were giving it our energy, but when he left, it changed the dynamic.

We also have many cases in Auroville of ‘Founders Syndrome’, people who have been associated with a process from its early days so that it has become part of their identity, making it very difficult for them to accept that the project needs to evolve. If anybody suggests this, it quickly becomes very personal.

Gijs: I can give you many examples of good ideas that didn’t happen. One was the Integral Sustainability Platform (ISP). It seemed very promising as it was going to revolutionise our organisation through interlinking different groups. One of the ideas I particularly liked was that the food group would talk with the mobility group, the water group and the logistics people. But the ISP went nowhere.

What happened with ISP, according to me, is that the Auroville group who initiated the process and hired the facilitators ended up in conflict with them, and lost control over the minutes and all documentation. So thousands of hours of meeting notes were gone, and there was nobody left to pick up the pieces and rebuild momentum.

Another example I can remember very clearly was the idea to collectively procure food for all the restaurants and food outlets in Auroville. We decided the easiest thing to begin with was sugar. We got a discount along with better quality sugar from a supplier in Chennai. But it began falling apart after a month because the logistics didn’t suit everybody exactly: the delivery day didn’t suit some people, or the packaging was not exactly what they were used to.

I thought if it is not possible to collectivise such small things, forget about attempting it with anything more complex.

It left a bitter taste, and the feeling that as we tried that and it didn’t work, why bother again? Everything that looks similar and has failed tends to be painted with the same brush, but were they really same thing or something rather different?

One of the stories we tell ourselves is we are a bunch of l losers: She gave us this job and we are just flunking. This is very disempowering. If you feel that, it is difficult for us to come together and heal ourselves. There’s a collective trauma which we are not addressing and which is holding us back. I think we need to process the hurt of past collective attempts at change, that failed.

Jaya: I go back to the twelve qualities. At Matrimandir, the petal of the quality of Generosity connects to the Garden of Power. Generosity is the one quality with the capacity to dissolve conflict without creating residue. When it comes to shifts or handovers of power we need to consider this very seriously if we are to create goodwill and support rather than pain and opposition.

Min: I have some examples of good ideas that failed. One was the Library of Things. We did a survey and many people said it was a great idea to have a place where people could bring items they are not using to be borrowed and used by others. But there was very little uptake, partly because while people are used to borrowing informally from neighbours, a more organized way of doing it was unfamiliar.

Again, when I broke my hip I realised we are paying a lot of money from the Health Fund to outside doctors who were not complying with Tamil Nadu standards concerning what they should charge. A few of us came up with the idea that there should be contracts drawn up specifying maximum charges. It was a very obvious thing to do, and I must have sent at least 70 emails to the Health Fund and the BCC with this suggestion. But it did not happen.

There are also challenges with teams. People join teams with different motivations. One person is inspired by the idea, another joins because of financial need, yet another wants to work in a spirit of service. How do you deal with these different motivations? It’s not like the outside world where the motivation is money and promotion, where you hire people to do a certain job and they do as you say if you are higher than them in the hierarchy. Here I can’t do that, so how to get it to work? I am constantly struggling with this.

Jaya: We are not aligning our actions with our ideals. Mother says that working together is the only way to do good work, which means accepting the two ways She proposed for Auroville’s organization: spiritual hierarchy together with divine anarchy. In the Participatory Working groups proposal this was the aim. But to succeed it needs time, patience, collaboration and the letting go of traditional power struggles, together with the inner work of freeing ourselves from the associated fears and desires.

We tend to evaluate success and failure in a very conventional way. What if seeming failure can lead to success, or open a gateway for something very different, many years later?

Jaya: Exactly. For me it was hell when the selection process was foundering because I could see what we had already achieved. But after one year of fighting for it, I could let go. While the initial impetus may seem to have failed, we actually did shift quite a few things and many of us had personal insights from it with which we can go on working and widening ourselves. So, hard though it felt at the time, I don’t think anything is lost.

Dave: I really didn’t want to be involved with the 50th anniversary planning group. But then I thought I’ll try through this process to get one idea moving which could become common currency. So I introduced a standard operating procedure which is very simple but which can be used to organise something huge. About a year later, the PCG were using a format that was very complicated, and somebody said, “Use this one instead. It’s much simpler. I wonder where it came from?”

Gijs: Actually, Auroville is notoriously bad at processes: we celebrate visions and individuals, but disregard methods. Also, we do not keep track. Once an attempt has failed, we ditch it and forget about it. There’s no institutional memory or an effort to create one, so we can’t learn and build on previous experience.

Jocelyn: It will be very interesting to look again at some of our old ideas and see if they have new relevance. For example, I think the circles idea, which failed when it was first tried, will work much better now in the context of the new ‘Prosperity’ proposal [which aims to create a self-supporting circular economy, eds].

Gijs: So maybe an original project failed completely but the tool found another application. This is fascinating. We don’t actually know a lot about how change works, so where can we have these conversations? How can we share this kind of learning?