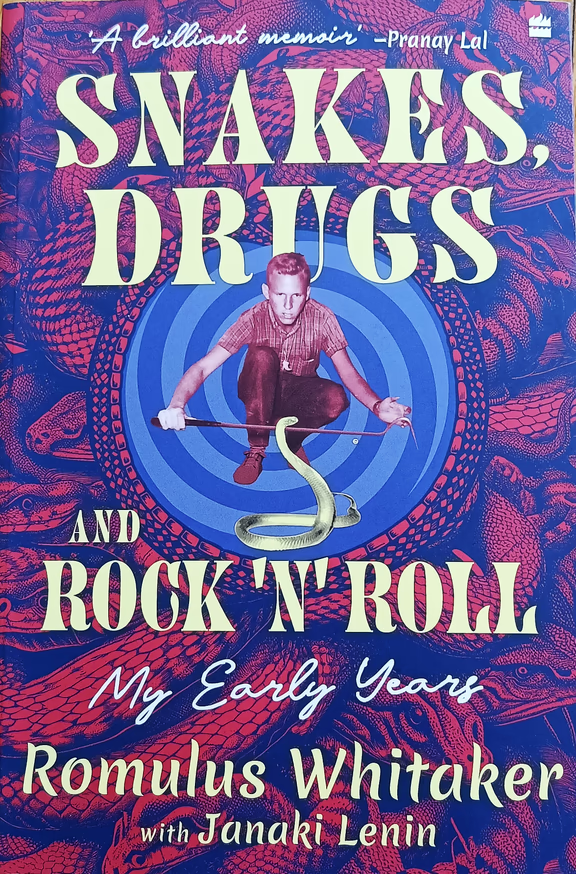

Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll: My Early Years

Book reviewBy Alan

Keywords: New publications, Books, Biographies, Wildlife and Snakes

Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll

After this, he has visited Auroville frequently and got to know the Auroville foresters, who advised him on how to plant trees at the Snake Park and the Crocodile Bank, both of which he set up. Our greenbelt experts also provided him with valuable advice when, as one of the founding members of the Palani Hills Conservation Council and the Irula Women’s Welfare Society, he was part of a team which planted lakhs of trees on degraded village land. For his work in wildlife conservation, he received the Padma Shri award in 2018 from the Government of India.

Recently, the first volume of his autobiography, which he wrote with his wife, Janaki Lenin, was published.

The first volume of Rom’s colourful autobiography only covers his first 24 years, but by then he had packed more into his life than most people manage in one or several lifetimes – as a hunter, taxidermist, salesman, merchant seaman, lab technician and reluctant army draftee. At school he kept a 6 foot python as a pet and experimented, among other things, with bomb making (during which, he admitted, he had been protected by the ‘god of idiots’). Later he experimented with marijuana and hallucinogens.

But his most important job was the two years he spent assisting with Bill Haast, the world’s most famous snakeman, at his Miami Serpentarium. In fact, ‘Breezy’, as Rom was universally known, had been fascinated by snakes and sought them out from early childhood (he was blessed with a very understanding mother), but it was at the Serpentarium that he learned how to extract venom and care for the assortment of snakes (as well as a 14 foot Nile crocodile) housed there. Bill often sent Breezy and his friends on snake catching expeditions, and during these we are introduced to colourful acquaintances like Attila, who claimed he could catch snakes best when he was stoned.

In fact, Rom seemed at times to be leading a double life. On the one hand, there was the laid back Breezy who drank beer and ‘toked’ with friends while listening to Dylan and Led Zeppelin (the ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ Breezy), and who dated a succession of attractive girls who – somewhat surprisingly – seemed fascinated by snakes and, on the other hand, the Rom who needed all his wits about him when catching venomous snakes or extracting venom, or matching blood samples in the medical lab. In fact, although he doesn’t make much of this, Rom had an extraordinary capacity to learn new skills, and this clearly required a great deal of commitment.

This autobiography is a breathless big dipper of a read; the pace never slackens. Most of the time the reader is swept along through his various adventures, although the many snake hunting expeditions described later in the book tend to blur into each other for those who are not committed herpetologists.

The pace, however, can feel exhausting at times, for what is missing, perhaps, is a certain sense of interiority, of Rom stepping back at times to reflect upon his many adventures. This is particularly important concerning his fascination with snakes – which, after all, are not everybody’s cup of tea. Apart from describing the beauty of certain snakes, Rom never gives us a real insight into what fascinates him about them. In fact, at times, as he drags a succession of them out from under rocks and stuffs them into bags, they seem merely a source of income for him, not extraordinary for him in any way. And how does the dedicated game hunter who shot and ate deer sit with Rom the conservationist?

Then again, after one of his experiments with hallucinogens, he remarks that “I was scratching the surface of a spiritual experience”, and a later experiment, when he had an out of body experience, made him remark, “Something had shifted permanently in my mind and the way I understood the world.” It seemed like a very important moment, but he doesn’t explain what had changed, nor does his subsequent behaviour in any way reflect this shift. Rather, it disappears into a continuum of experiences, giving the impression that he was always simply living in and for the moment.

To be fair, Rom makes no attempt to hide the possible contradictions in his nature. In fact, in the preface, he states, “This is what I was and still am to a large extent – contradictions, complexities and all.” And it his honesty, his refusal to varnish or justify some of the less salubrious aspects of his life, that makes this autobiography so engrossing.

We look forward to reading the next volume, out later this year, where he will talk about setting up India’s first reptile parks, creating a livelihood for the Irulas selling snake venom, and getting hired by the UN to set up crocodile farms in Africa and Asia. The final volume will be about making films and his snakebite work.