Defining Mother, losing Mother

ReflectionBy Alan

Keywords: Nature, Trees, Forests, Mother’s Agenda, Transformative work, The Mother’s life, The Mother’s Mahasamadhi, Words of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother and Psychology

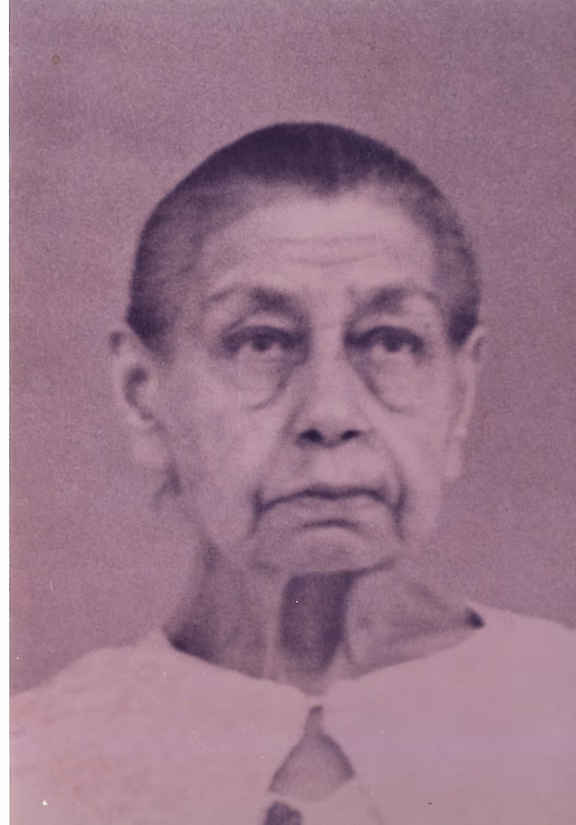

The Mother

Some of Simard’s original co-authors and other researchers subsequently questioned some of her findings, noting that some of her claims outstripped the evidence: that, for example, seedlings connected in fungal networks to older trees often do worse, not better as she had claimed. However, the image of a conscious, collaborating forest proved irresistible. The magazine Nature dubbed it the ‘wood-wide web’ and The Hidden Life of Trees became a bestseller.

It is not difficult to understand why the image of a caring forest has rooted itself so deeply in the public’s mind. It is attractive because it humanises it, making it more recognizably like us. Moreover, Simard’s concept fits with the current zeitgeist which prefers to view the natural world as cooperative rather than competitive.

But by labelling or repackaging the forest like this something essential is lost, and that is the sense of the forest as something ‘other’: powerful, profound, yet unknowable in human terms. (And perhaps this is what we fear – that we live in an unknown and unknowable world, which is why we need to humanise it.) In Bill McKibben’s words, “We have deprived nature of its independence, and this is fatal to its meaning.”

I wonder to what extent many of us are doing the same with Mother – ‘packaging’ her to make her more understandable or amenable to us but losing something essential about her in the process.

Mother was very aware of this. In 1954 she observed, “It is their (devotees’) own mental and vital formation of me that they love, not myself… Each one has made his own image of me for himself in conformity with his needs and desires, and it is with this image that he is in relation…”

And in 1970, talking of the devotees’ propensity to see all the workings of the Divine concentrated in one person as the ‘one and only’, rather than seeing such individuals as special concentrations of a larger Force which is acting everywhere, Mother protested, “I absolutely REFUSE to let myself be put like this (gesture under a bell jar)…I’d rather – I’d rather dissolve, you understand. Let it be fluid. The impression I get is as if people have big scissors, and they always want to cut out pieces of the Lord!”

So how do devotees view the Mother? I think that many devotees cherish an image of her as the ‘motherly’ Mother or, conversely, worship her as the divine goddess. What few would like to recall is the Mother of those final years who, while remaining a being of extraordinary power, spoke of her own sense of powerlessness as she wrestled with the yoga of the physical, and struggled with periods of excruciating pain which alternated with moments of extraordinary bliss. She spoke, too, of her doubts and uncertainty, of the attacks of the hostile forces and of the incomprehension of those around her. For she sought a way to change the world, but the world resisted and her final years were difficult and painful as she strove, often on the edge of physical death, to supramentalise the cells of her body.

This is heroism on a scale beyond anything we can comprehend. Yet it is an aspect of Mother which is rarely talked about or celebrated, not because it is unknown – even in her lifetime extracts of her struggle to supramentalise the body were being published, with her permission, in the Bulletin of the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, and since then a far more comprehensive documentation of those final years has been published in The Agenda – but because this is not a comfortable or comforting Mother. Moreover, this is an ‘unfinished’ Mother, one who had not obviously succeeded in finishing all the transformative work she had been engaged upon.

Yet, what is also evident is that in her final years, in spite of her difficulties, Mother was moving at breakneck speed in making new discoveries, guided by the consciousness of what she termed the ‘surhomme’. And what she discovered through her explorations, which were now concentrated in the physical, completely changed her former understanding and outlook:

“I have very much changed, even in character, in comprehension, in the vision of things. There has been a whole rearrangement.”

“This poor body cannot say anything because it knows nothing; all that it thought it had learned for ninety years has been demonstrated most clearly to be worthless! (Mother laughs) It’s been shown that it has everything to learn.”

“We know nothing! It’s amazing how we know NOTHING.”

This is not at all easy to comprehend, and even harder to accept. Many of us don’t want a Mother who is admitting to ignorance. We want a Mother who we can look up to, who is assured. We want a Mother who ‘completes’ us, who is everything we are not. It is why there is a tendency for many of us is to remain focussed upon an earlier Mother, upon, say, the Mother of the Entretiens who seemed to know so much (and, of course, who can continue to teach us so much), even though, in her final years, she viewed these talks rather differently:

“These are things I would certainly no longer write now! ... But anyway, they are true on their level (gesture at ground level).”

By freezing an image of Mother in our heads, many of us ignore or have difficulty engaging with the ‘unfinished’ Mother who hadn’t yet ‘arrived’, the one who, while unsure of her steps, was ceaselessly voyaging into the unknown. By attempting to define Mother, we have put her under a bell jar and lost touch with the ‘fluid’ Mother whose radical indefinability was her refusal to be bound by human limitations for, as she put it, “The world is recreated at every moment”.