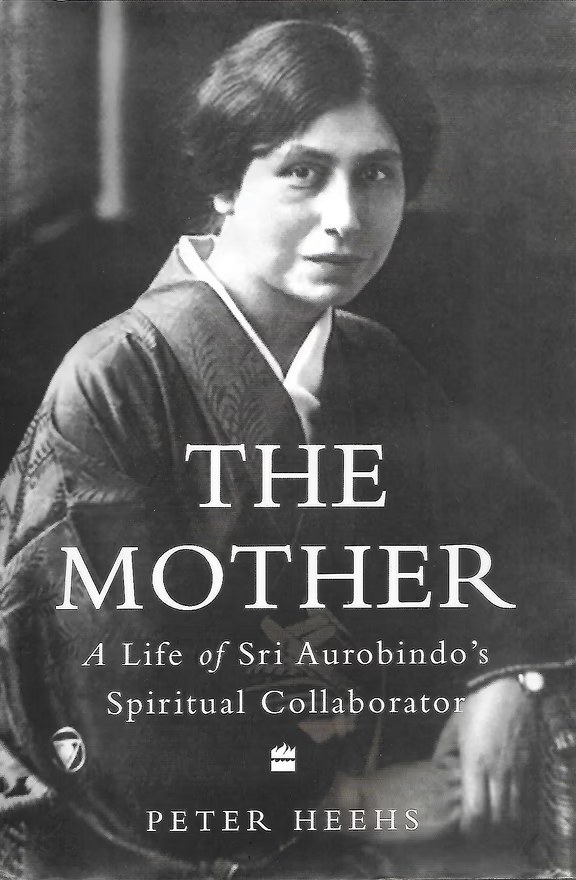

The Mother: A Life of Sri Aurobindo’s Spiritual Collaborator

Book reviewBy Alan

Keywords: New publications, Books, Biographies, The Mother’s life, Historians, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Archives, Paris, France, Japan, Algeria, Spirituality, Avatars, The Mother’s Mahasamadhi and Occultism

The Mother: A life of Sri Aurobindo’s Spiritual Collaborator

In fact, what the new biography does very well is to create the ‘texture’ of the different milieus – Paris, Tlemcen, Japan –in which The Mother developed herself and became aware of her spiritual mission. It also touches upon the political pressures, both local and national, which influenced life in the Ashram, and highlights her attention to the daily details of running such an institution even while she continued her groundbreaking spiritual work.

During a recent informal interchange Peter expanded upon why he had written a new biography of The Mother and why he adopted a rather different approach from that of her earlier biographers.

Auroville Today: There are already a number of biographies of The Mother. Why the need for another?

Peter: I wouldn’t have taken this up if I hadn’t been invited to do so in 2020 by the historian Ramachandra Guha, who was starting a series called Indian Lives about extraordinary individuals who had been active in different fields.

Right around this time a few things came together. Firstly the papers of a friend, Francis Bertaud, came to Pondicherry after his unexpected passing. He had spent several years in the Ashram, where he was known as Pushan. While here, and later in France, he did a great deal of research into the Mother’s ancestry and early life. In Paris he became close to the Mother’s granddaughter, Janine Panier, and she shared some material with him. I helped Pushan sort through his material while he was in Pondicherry and resumed this work after his papers arrived in 2020. I also did a good amount of research on my own both before and after 2020 and wrote a couple of papers about aspects of the Mother’s life, in particular about her relationship to Théon and his wife.

For this sort of research, the internet is an invaluable aid. I have a particular interest in late 19th century and early 20th century French art. The Mother was part of that scene so I wanted to situate her more fully in that world. Of course, she wrote about this herself, but a historian cannot be satisfied with just one person’s account of where things stood at that time. One has to go to the sources and many of these are now online. I was able to learn a lot by, for example, searching for references to ‘Alfassa’ and ‘Morisset’ on the online site of the French National Library.

Guha’s invitation came around the time that I was immersing myself in this new material, and I began to feel it was possible to write a new biography in order to fill in some of the gaps and write something that would do justice to all aspects of The Mother’s life.

I had more time for this than I might otherwise have had because the invitation came while Pondicherry was under partial lockdown owing to the Covid-19 pandemic, and I wasn’t going to the office as often as usual.

In addition to including new material, did you also wish to present The Mother’s life from a rather different standpoint?

Yes. People who write about biography use the terms ‘contingent’ biography and ‘teleological’ biography. A teleological biography, which I term an ‘omega’ biography, views events in a subject’s life as inevitable steps leading to a preordained conclusion. A contingent biography, which I term an ‘alpha’ biography, follows the subject’s life from birth to an uncertain outcome. It is more like a diary record of events as they happen, day by day, recording the response of the subject to these events.

All the previous biographies of The Mother that I know of take the ‘omega’ view, which is viewing all the preceding events in her life as leading inevitably to a certain conclusion: they want the ‘achieved’ person to be present from the beginning.

Which is what hagiographic accounts tend to do.

Yes. This is not to say that this approach is wrong. It’s fine and I have learned a lot from such books. But generally, at least among scholars, this approach is not favoured because obviously you’re trying to fit the life into a predetermined pattern, and life is not lived like that. Guha, being a historian, wanted something academic, and this suited me fine because I like to present my research in an academic way. So I adopted the ‘alpha’ approach in this biography.

This makes sense when writing the biography of an ‘ordinary’ individual where you can assume that their development was contingent upon events which happened to them. But isn’t it different when you are writing about a spiritual figure like The Mother who said, among other things, that she had been doing sadhana in the womb and that she had chosen her parents before conception?

I agree that when you write about a spiritual person it’s a lot more difficult because you are dealing with somebody whose consciousness is quite different from ours. This is why the teleological way of looking at things is often favoured in such cases.

However, I write on the assumption that she was not born with a prevision that she would take to the spiritual life, that her sense of spiritual vocation emerged gradually over the course of five decades, and that at every moment she had to deal with the contingencies of a complex life. In choosing this approach I was happy to come across a statement by Sri Aurobindo. He had been asked why a spiritual figure like himself had had to go through all that ordinary stuff, like getting married, and he replied, “Do you think that Buddha or Confucius or myself were born with a prevision that they or I would take to the spiritual life? So long as one is in the ordinary consciousness, one lives the ordinary life – when the awakening and the new consciousness come, one leaves it – nothing puzzling in that.”

There are also statements made by him regarding the extreme struggles experienced by himself and The Mother. If everything was preordained, these struggles would not count for anything, and nothing could be learned from them.

Could one combine the ‘alpha’ and ‘omega’ viewpoints by saying that the spiritual potential of figures_ like Sri Aurobindo and The Mother existed from birth but that their understanding of that potential developed through circumstances—like The Mother being given a hint about how to read the Bhagavad Gita, or her contact with the Théons which gave her a new framework to make sense of what she had been experiencing?_

Sure. You could say that what Sri Aurobindo was identifying in that quote calls for a kind of ‘alpha plus omega’ approach to their biographies. In other words, once you get into the higher consciousness there is a fundamental change in outlook, but while you are approaching it you are approaching it step by step.

So, in figures like this at a certain point the spiritual development is no longer contingent upon outer circumstances?

Yes. When Mirra Alfassa is declared by Sri Aurobindo in 1926 to be ‘The Mother’ and when he writes the pieces which became the book The Mother, most members of the Ashram believed – even though he did not say so directly – that he identified her as the individual Divine Mother who mediated “between the human personality and the divine Nature”, as he wrote in the sixth chapter of that book. I discuss this in my biography, then pause to consider how a biographer should deal with this identification. One could view the rest of her life as a seamless manifestation of divinity or one could look at how she continued to deal with the contingencies of life.

It is clear that from that turning point, things have to be viewed in a different way, but as a simple biographer who makes no claim to having any special knowledge of what beings like this are like, it seemed the best course for me to view The Mother’s development from 1928 until 1973 as a step-by-step process, basing myself on what documents were available.

Any biographer necessarily shapes the material available on their subject by making decisions about what to highlight and what to ignore. One thing I note in your biography is a certain avoidance of what might be termed the later occult work of The Mother. For example, during your coverage of World War Two, which Sri Aurobindo termed ‘The Mother’s war’, you don’t mention The Mother taking on the appearance of the Lord of the Nations to deceive Hitler into attacking Russia.

When you take up the task of writing a biography, you have your own view of things, you have the material and you have the intended readership. All of these influence what you choose to put in the book. Regarding the readership, I would tell the whole story differently, say, to people in the Ashram or Auroville, but this is not the readership the publisher is looking at. They are looking at a wider readership. All this shaped the way I went about my research and presented it.

Regarding the occult, apart from it appealing only to a limited readership, I really don’t know how profitable it would be for me, a historian, to talk about that sort of thing. It is quite possible to go overboard when you enter into that area and then you end up, as some biographers have done, pontificating about such things without having any real knowledge about them.

So I think it’s good to stick to what is solid – tangible things that people can use in their own lives. In writing this biography I had a rather modest goal. I just wanted to put together authentic material that could fill in the account of what The Mother did and present it in such a way that people could use it to build up their own conception of what she was.

My approach is to keep my own feelings about the subject to myself – to be respectful, fair-minded but not excessively demonstrative. It is not up to me to tell people how they should feel about The Mother. But I can tell them, for example, when she exhibited this painting or met that person or had that spiritual experience – things for which I have the documentation.

Most ‘omega’ biographies of The Mother end with statements like she had achieved a supramentalised body, that she would return in this new body and that her death was actually a kind of victory: as one disciple put it, it was a “master-stroke of conquering all while appearing to perish utterly”. You do not make any such claim.

Some people may well have had an experience like this. That’s okay, but I don’t think you can impose it on other people as a ‘fact’. For most people things like that are, necessarily, speculative. Everyone is free to speculate, of course, but I tried to stick to what the documents say. One thing that is certain is that she was trying to transform her body in this life and eventually achieve something like ‘integral immortality’, which was the term she first used in 1904. Sixty-nine years later this was still in the forefront of her consciousness and she was working very hard to achieve it – but what actually happened during the last years of her life is hard for us to determine. People can say they had visions or intuitions about her, and that is fine – for them. People can put together statements that she made and arrive at certain conclusions. That also is fine, but there’s really no way to be certain about what actually happened.

However, I think there is quite a lot we can do ourselves which doesn’t require us to have exalted notions of what happened. We can keep ourselves busy by contributing to their work and to the aim she set before both the Ashram and Auroville: that of spiritual growth leading in the end to the establishment of an ‘ideal society’ in which a ‘new race’ could evolve.