Perspectives on the Auroville Foundation act

ReflectionBy Frederick

Keywords: Perspectives, Auroville Foundation Act, 1988, Residents’ Assembly (RA), Governing Board, Shantiniketan, International Advisory Council (IAC), Sri Aurobindo Society (SAS), Auroville Foundation and Authority

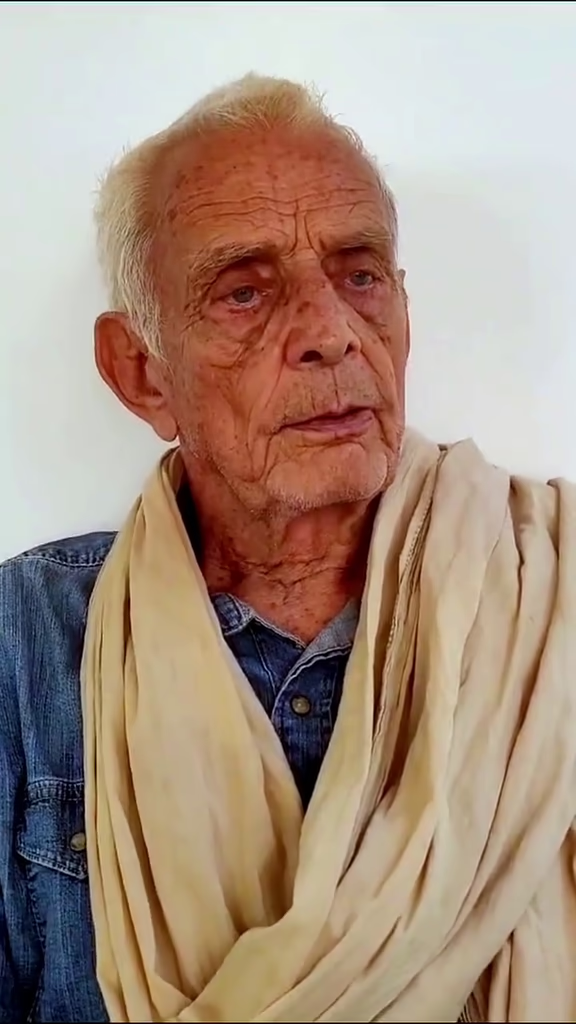

Frederick

One perspective, represented by Kireet Joshi and, to some extent, Satprem, emphasised not fixing Auroville’s evolution into a rigid structure – keeping it open for flexibility. Others, like JRD Tata, Fali Nariman, and Palkhivala, argued that if something is written into law, it must be clear and cannot be left open-ended, as that would invite misuse.

Originally, the Act recognised only the Residents’ Assembly. However, a parliamentary secretary questioned what the Residents’ Assembly was and insisted that it needed a clearly identifiable group to represent it in Parliament when necessary. To address this, the Governing Board was inserted in between – though its role was never meant to be one of governance in the traditional sense.

Indira Gandhi, having seen what happened to Shantiniketan when the government took control and turned it into a department, wanted to prevent the same from happening to Auroville. To safeguard its independence, she created the International Advisory Council, which was initially meant to advise the government to ensure Auroville did not become a government-run entity. However, it was not legally possible for an international body to advise the Indian government, so the Council’s role was redirected to advising the Governing Board of the Auroville Foundation instead.

Now, looking at these minutes, two major concerns stand out – both of which violate the very spirit and intention of the Act. The two biggest concerns that stand out are the emphasis on “ambiguity” and the push for “strong administration”.

At the time, what is now being called ambiguity was actually understood as flexibility – leaving space for Auroville to evolve in its own way, in its own time, in the Grace. The idea was that Auroville would find its own structure as it grew, rather than having one imposed externally. JRD Tata had questioned how the Residents’ Assembly would make decisions, warning that if it was left completely open, it might never function effectively. And indeed, over 45–50 years, we have seen how difficult it has been to reach consensus or even a majority decision. But that is precisely the challenge Auroville was meant to take on – a model of collective self-governance that the entire world is struggling to develop.

It is painful to now witness this original openness being reinterpreted in a hostile and anti-spiritual manner, turning the vision of mutuality – these three bodies working in harmony and with respect for each other – into something seen as a flaw. We can only hope that if any new framework is to be developed, it emerges from within – through the collaboration of Auroville’s three constitutional bodies – rather than being imposed from above.

The second major concern is the push for strong administration. This has always been the issue with the Sri Aurobindo Society and the very thing Auroville has fought against – a top-down approach to governance. The signs are clear: selling off land outside Auroville, enforcing a rigid administrative structure, and reshaping Auroville’s identity into something that aligns with today’s dominant political ideologies. The painful reality is that falsehood is not always the direct opposite of truth. More often, it is the truth – twisted. And that is what we are facing now.

I do not know what the future is for us. But I do believe that India, at its core, holds the wisdom to recognise Auroville as a gift to the world. If it is allowed to evolve from within – rather than having something imposed from above – Auroville can fulfill the vision it was meant to embody.