Auroville will always be my home: Binah’s story

By Binah

Keywords: Personal history, Early years, Meeting the Mother, Silence community, Sri Ma / Far Beach, Aspiration school, Ami community, Alankuppam, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Delhi Branch, Kodaikanal International School, United Nations, Development aid, Auroville International (AVI) USA, United States (USA), Multi-cultural relationships and Spirit of Auroville

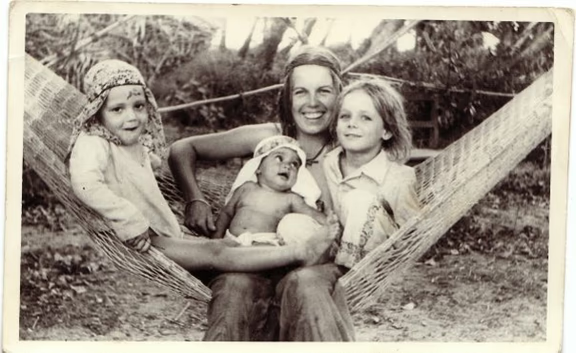

Binah, AuroJina, Aruna and Jonas taken by ran

Binah

I first came to Auroville in 1969 with my Mom, when I was about eight months old. We went to see the Mother quite a few times, but I don’t remember being in the room with her. I remember leaving the room, and Champaklal running after me and giving me a big box of chocolates and flowers.

At one point, my grandfather and grandmother came to rescue me from this crazy trip to India, and my mom said, in the blind faith of the time, “Go see Mother. If you still feel like you need to take Binah, then take her.” So the myth is that my grandfather went to see the Mother with a basket of flowers, and he was smoking a cigar, which is pretty unacceptable in the Ashram. Apparently, the staff there were rushing to put it out, and Mother said something like, “Oh leave it. It reminds me of Sri Aurobindo.” Whether that’s true, you have to ask someone else!

Apparently, my grandfather came out of Mother’s room, put the empty flower basket on his head and skipped down Beach Road, very happy and inspired by his experience. He visited Auroville five times during the early ‘70s, and was so inspired that he supported it in many ways: he paid for the bore well and electricity poles for Silence community; sent books to the school in Aspiration; helped Cow John start the first Auroville dairy; and he sent gifts to the Mother, whom he liked very much.

After that, my mother started the community at Far Beach, which is now named Sri Ma, so we lived there. For preschool I went to our beautiful school in Aspiration which was filed with adults from the Ashram and Auroville who were inspired by Mother’s love of children. We then went to America for a couple of years, and came back when I was seven and moved to a forest community near Verite. During that time our amazing school in Aspiration was shut down and I went to school at Center School but it was really only for really young kids. My mother stayed in Silence and I went to live in the community run by kids at Ami. We were quite sweet kids, aged 6-13. The core was mostly girls: Grazi, Dorle, Tashi, Kesang, Kathrin, Marta, Miriam, Nelly and some others. We were a magnet for other kids to come. Kids such as Sasha, Alok, Giri, Jonas and Isaac came and went – they didn’t really live there.

It functioned well. Sometimes adults stayed there to provide security, such as Claire and Nico, and other adults like Johnny and Joan popped in and kept an eye on us, but there were no adults in charge. Some teenagers – Kathrin, Miriam, Marta – herded us around, enforced some rules and made sure we did laundry. We received a generous Pour Tous basket for kids, and we cooked all our food in the community kitchen. We had lots of good times together. When the politics in Auroville didn’t always make sense, we made sense as a family. I don’t know why they let us run our own community – it was never done before or after! It’s not the sort of thing I’d let my own kids do, but we had a great time. It was pretty cool!

We’d go and visit our parents on weekends. It was a time when parents were very busy building this new world, so I don’t think they were too sad to not have us there. We kids had more structure by being together than if we’d been living apart.

I felt very comfortable around Tamil culture, and I spent a lot of time in the teashops in the village. Bhoomadevi used to take me to Tamil movies in Alankuppam, where I was often the only foreigner. Before going, we’d put powder on our faces, flowers in our hair, a puttu on our foreheads. We also went to village festivals with Johnny. He would put us in a vandi [bullock cart] and take us to the fire walking in Edayanachavady. Our borders with the village kids were permeable. I slept many nights in someone’s hut in the village. I got to see a lot, and I feel privileged. Now that I have a Tamil husband, it’s good to know the culture a little and be comfortable with it.

I then had the privilege of going to the ashram school in Delhi, for three years from 5th to 8th grade. It was hard going to a proper Indian school and wearing a uniform, and it was overwhelming being in a dorm with 40 kids. I was the only foreigner, and the kids would come up and say, “You looted us,” confusing me with British colonialists. But kids are forgiving, so I eventually made some great friendships. After three years, I could read the Mahabarata and Ramayana in Hindi and I became very comfortable in north Indian culture.

Back in Auroville, we Auroville kids were doing some schooling with Johnny, and at one point, we wanted a proper school and we went to him and said, “We want chairs and desks. We want Math and English.” He was surprised that we wanted so much convention, but we were hungering for structure. Being as open-minded as he was, he was willing to give us the form of education we wanted.

By the time I was a teenager, most of the kids in the Ami community naturally went in different directions. Some of us went to Kodaikanal International School, but we would stay in Ami when we came back to Auroville on holidays. Giri is still there in Ami – the longest standing member at this point!

In Kodaikanal, we didn’t have to be in charge of laundry or cook meals. We just had to show up to classes and do homework, in this beautiful place. That was so easy after the adult responsibilities we had had. It was fun and I didn’t find the rules inhibiting. All the kids who went to Kodai at the same time as me – Alok, Nelly, Stephanie, Isaac, Jonas – enjoyed it very much. It was a privilege for us, coming from Auroville where there was only informal schooling.

I went to the USA for college, and I came back and forth to Auroville a lot during those years. I did a Bachelor degree in Government and History, and then I got a Masters degree in International Development Management. I then did village development work at an ashram outside Bombay for 18 months. I trained there with World Vision in their ‘participatory rural appraisal’, a technique which uses alternative methods to spark an internal conversation in villages to analyse current issues and to propose what they want to do next. With this approach, the development workers are merely facilitators for the villagers’ analysis, and the village has to take ownership of the process. Only at that point are funds provided. In the past, the UN and many organisations have done development projects where outsiders come into villages, build things and then leave, and then the building or project collapses. The challenge for well-intentioned development work is: How do you make things that won’t just be a monolith to failed foreigners?

After my studies, I worked in Washington DC for the Agency for International Development, and then I got a job at the UN Development Programme in New York City. I worked on programmes that aimed to empower local populations to solve their problems. We targeted small informal groups that were not officially on the development radar, such as women’s groups, midwives, singing groups. However, the UN is a very big political organisation. If you think working for one government is hard, imagine working for many. Coming from Auroville, I was very idealistic about being a bridge between cultures and making a difference in the world, but I saw a lot of waste and expenditure in these organisations, which blew my mind. The distorted perspective of how we use wealth and power was bizarre to me. So I realised the people who make the biggest difference in the world are those who start from inside their own sphere of influence, with their neighbours. When you work locally, you are also a stakeholder. If you fail in your promises, it has an effect on your own life as well as other people. It is one of the advantages Auroville has, that it is here to stay.

For a while now, my main job has been as a mom. I live in Denver Colorado, and I work at a pre-school, where I support their resources, library and art programme. I get to challenge teachers to think outside the box, and to be supportive and inspirational. That’s been fun. I always wanted to come back to Auroville, but I was always trying to figure out the next step, both financially and academically. It was just ‘one foot in front of the other’ that led me on the path I’ve been on.

I’ve been working with AVI USA for a couple of years. I recently became the president and I appreciate that I can work with these wonderful people, some of whom were there in Auroville in the early days. They are full of hope that Auroville can make a difference in the world.

My husband is Sri Lankan Tamil, and he grew up in America. In a lot of ways, we are opposite sides of the same cookie. People think he’s the Indian one, and I’m the American one, but it’s really the other way around – he has more experience with American culture than I do, and vice versa. It’s good to know Tamil culture a little bit, but my Tamil friends in America laugh at my spoken Tamil, because I don’t know the polite form of speaking, so I often sound rude! As a kid, I always felt that I had so much more to learn about Tamil culture. I always thought we would grow into a deeper understanding of this rich and ancient culture – like I had the opportunity to do with North Indian culture. Perhaps because of our deep ties with the Ashram we seem to have a better grasp of North Indian traditions. We have the informal understanding of the villages around us but I think we need the formal understanding of Tamil culture from books and scholars, and the thevarams (Tamil bhajans), in order to start to appreciate how nuanced and soulful our local culture is.

This is my first visit to Auroville after five years. It’s so good to be back. When I’m in America, I have a sense that I’m an island that’s floated off from the mainland. People want to know who and what I am, but I’m not American really, I’m not Indian, so I have a sense of loss of culture. And everybody who knows my history is here in Auroville. When I come back here, I’m rooted. So there’s a deep affinity with so much – I drive past places and remember things, and think, ‘Oh look at that!’

The quality of life in Auroville is so much higher now, it’s incredible. Food was a big issue in the early days, but now everyone’s well fed and there are so many restuarants. There’s centralised water and electricity – all these things were unimaginable to us then. I’m struck by all the guesthouses being built around the edges of Auroville. The lure of these comforts is strong, and Auroville has become very attractive as a tourist economy. I enjoy having AC when I visit. I know the young me would have made fun of the older me, but the older me loves the comfort!

Yet I question the cost: how do we not just become another town or another tourist economy? How do we push our vision in terms of ecological and spiritual understanding, and new forms of politics and economy, without falling into the lure of having these wonderful modern things, such as fast internet and video in our homes? All of this has a benefit and downside. How do we walk that balance and stay true to ourselves?

I love the existence of things like conflict resolution – we never had that before. There’s an attempt to create harmony in so many ways. But here too, as we create more processes to address the needs of a growing Auroville, we tread a fine line between effective groups and an encumbered bureaucracy.

The biggest challenge with a collective governance process is that “the squeaky wheel gets the grease”, that is, the people who step forward to lead are generally the extroverts, and not necessarily the most wise or thoughtful people. So how do you create a collective process where you tap into the people who are not talking? I think it’s a challenge. There are very good people in Auroville constantly revamping this process with very good intentions. But it may be a challenge to be sure we are tapping into the collective wisdom of the most silent or overlooked people.

I’m impressed by the variety of people in Auroville. I don’t know if we always embrace our differences, but we seem to celebrate variety. A big question for me is: how can we live in harmony with our local environment and with India, before taking on the rest of the world? I can’t answer that, but my belief coming from development work is that you start from the inside out, rather than the outside in.

Coming back, I’m reminded of all the good will and love I received when I wandered Auroville as a child: all the people who parented me, fed me, gave me good advice, tucked me in at night and hugged me. I probably ate and/or slept in almost every house in the greenbelt. It’s great I can revel in all these people and places again. And it’s not that I don’t see all the politics and cynicism, it’s just that I don’t care about it. It’s like a parent-child relationship – you get to a point where you look at your mom and think, ‘Thank you for giving me life’, and all the other things don’t matter so much. You become an adult and take ownership of your life, and you write your own story. My story is that I grew up in an incredibly magical place, where I got to do the wildest things. I have so many great stories to tell my kids, and they’re blown away because their lives are relatively mundane.

I’m a child of this place so it will always be my home and I will spend time here in the future. My kids have been a few times, and I can imagine this place will draw them back. When I see my friends and former teachers who have stuck with Auroville through the years, I see a lot of determination, passion and deep-seated devotion, and I think, ‘Auroville will do great things’. When I sit in the Matrimandir meditation chamber, I think ‘Wow, we created something special here.” I remember thinking it would always be a construction site.

When I’m in America and I think of Auroville, I think of the smells and sounds, such as the brain fever bird at night, and the imam in the village singing the morning prayers in his beautiful voice. I also think of that line in one of Johnny’s songs from a play about Tomorrowville: “It’s not just a place, it’s a state of mind!”