“I am prayer only”

Book reviewBy Carel and Christine

Keywords: New publications, Books, Ashramites, Auroville history, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education (SAICE), Auroville Emergency Provisions Act 1980, SAIIER (Sri Aurobindo International Institute of Educational Research), Centre for International Research on Human Unity (CIRHU), Auroville Foundation, International Advisory Council (IAC), Governing Board, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, New Delhi and Auroville Press Publishers

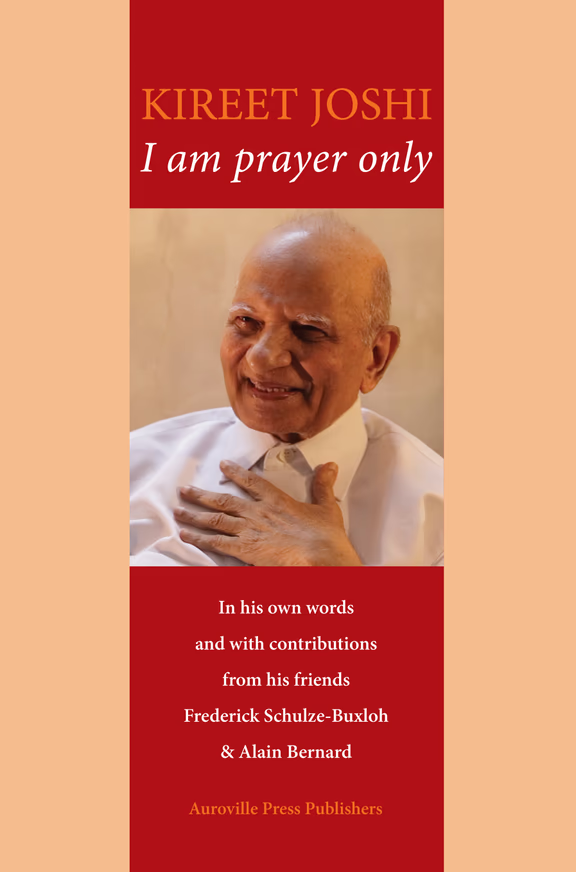

8 Kireet Joshi bookcover

Extensively quoting from Kireet’s unpublished memoir “Notes of a Servant of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother,” and interspersed with their own remembrances, the book deals with many topics from the life of Kireet. His early life, his meeting with The Mother, and his work as Registrar of the Sri Aurobindo Centre of Education take the first 50 pages. This is followed by his life in New Delhi, first as Educational Advisor to the Government of India, later as Special Secretary to the Government responsible for programmes relating to all aspects of education. It was in this period that Kireet battled for Auroville to get the Auroville Emergency Provisions Ordinance passed, which was later replaced by the Auroville Emergency Provisions Act 1980. The book describes the challenges he had to overcome to prove, through his lawyers, to the Supreme Court of India that Sri Aurobindo’s and The Mother’s teachings do not constitute a religion and that Auroville is not a religious institution. In that same case, the Supreme Court acquitted Kireet from having any malafide intensions in helping formulate this Act.

The book then deals with the necessity of the creation of SAIIER, the Sri Aurobindo International Institute of Educational Research, in Auroville; it is followed by an extensive section on the Auroville Foundation Act, its necessity, its concepts and its passing in the Indian Parliament. Kireet’s work to get all this done, always attributed by him as a result of his prayers to The Mother, reads like a novel, with one amazing development following the other.

His extensive knowledge of the writings of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother and his vision for Auroville’s development led Kireet in later years to push for the building of the Centre for International Research in Human Unity (CIRHU), which was conceived by Roger Anger, the architect of Auroville. This project, however, is still to take off. The book also contains some of Kireet’s views on Auroville’s economic ideals and its internal organization.

In 1999 Kireet was appointed as Chairman of the Auroville International Advisory Council and, some time later, as Chairman of the Governing Board of the Auroville Foundation. Alain and Frederick contribute their personal reminisces about this period. The two appendixes to this book contain Kireet’s views on how education in Auroville should develop. But his chairmanship was not an easy time for Kireet, as he was drawn into a dispute regarding the Matrimandir management; it made him feel that he had been rejected by the Aurovilians, a feeling that only dispersed in later years.

The book, in a separate appendix, describes Kireet’s other works before he joined the Auroville Foundation. His deep interest in the old spiritual knowledge of India led him, in 1987, to create and become Vice-Chairman of the Rasthtriya Veda Vidya Pratishthan; this was followed by his Presidency of the Dharam Hinduja International Institute of Vedic Research, which he helped found. When his Chairmanship of the Auroville Foundation ended, he worked as Chairman of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research; and later as Educational Advisor to Shri Narendra Modi, then the Chief Minister of Gujarat. All these works were done in the same devoted dedication to Sri Aurobindo and The Mother. In 2010, after a very intense crisis, Kireet returned to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, where he passed away in 2014.

This book is called “I am prayer only,” wrote Frederick in the epilogue, explaining that “each one of us is on earth for a particular reason and that it is our job to find that reason. While the call is upon the individual to find its own instrumentality, it is also the search for one’s part in the collective body. We are born like a prayer. Kireet, as a true pioneer and forerunner, brought this light, this consciousness, this awareness to the body of Auroville … We can join in the special prayer he represents.”

Kireet Joshi: I am prayer only.

Available from the White Seagull bookshop at the Auroville Visitors’ Centre.

Price in India Rs 490.

From the forward to “I am prayer only”

Kireet Joshi was many things to many people: administrator, guide, Ashramite, scholar, guru, professor, adviser, boss, speech writer, philosopher, sanskritist, and probably so many other things that we don’t even know. People called him Kireet, Kireetbhai, or Professor Joshi, or Dr. Joshi, or Uncle, or Sir, or Joshiji, but to us Aurovilians, he was Kireet.

Kireet. He seemed to us a little of an extraterrestrial. First there was his imposing skull, smooth, elongated like in the pictures of some Mongol kings. Then there were his eyes, amazingly small, almost only a slit when they smiled behind the thick and round glasses. He would arrive fresh, impeccably dressed in white, holding under his arm a volume of the Sri Aurobindo Birth Centenary Library, a book that seemed to be a hundred years old itself so many times it had been handled. His face, round, full, open, glowed with happiness, or rather I would say, with delight – a delight that seemed to flow from some mysterious source that was his own but that he was ready to share with everyone. The impression accentuated when he took your hand into both of his. Nothing could be compared to the feeling of softness you got: you entered a protective space, padded with something incredibly warm and spacious and comfortable and reassuring.

In the little group of Aurovilians, questions were raised, stories were told, discussions started, disagreements were expressed.

Then he would speak. He would summarize the problem, analyzing its components, which usually were three in number. After a methodic exposition, he would then broaden the whole topic, enlarge it to new dimensions altogether. The problem on which we had been breaking our head, in front of us gradually turned into a learning material. With the right key, with the right references, the matter which seemed inextricable was transformed into a tool for progressing and for beginning to understand the depths of life, the different planes of our being and the different planes of the invisible world. At that point very often he would refer to some text of Sri Aurobindo; he would quote it. Someone would be asked to fetch the book. The book would be brought. He knew the chapter, the page, the line.

There would be a moment in his speech when progressively his sentences became shorter, less didactic, more insistent, more repetitive. It was like a plane finding its right speed and right height. And at a certain moment something was seen. That was it. His voice then took on a new enthusiasm and resonance. It was as if at last he could seize in its entirety what he had been looking for. Something that was hidden before was being revealed clearly in front of us all. So his words were rejoicing as it were, they kept bouncing, coming back to that same point again and again, re-formulating it in various manners, abundantly, effortlessly, in the simplest and most creative way. It was an exhilarating feeling.

We were elated. Things seemed to have become miraculously easy.

They were not of course. Nevertheless the words uttered on that day, many of us would carry them in themselves for years and years. They would not be erased by time. If at all they have become more relevant, more urgent than before.

He could be stern and severe. At times. I experienced this mood of his twice. Once I was in his house in Talkatora, New Delhi. He came to me, asking me why on earth children of Auroville were coming for some camp organized by the Delhi Ashram. What were we thinking of? I did not know anything about it, I was dumbfounded but I remember his displeasure and it made me tremble.

Another time was when I showed him our slide-show on Sri Aurobindo’s Independence Day message. He was displeased because we had included the passage on Sanatana Dharma of the Uttarpara speech. This was not to be used, he said, as this text dated from before 1910, and according to the Mother this was not yet the real Sri Aurobindo. Yes, he conceded, some political parties might like this very much, but those are people who reduce his message and interpret it in a narrow way for making it serve their own purposes. We were not to do the same.

He could be sad. I remember a dinner in Delhi; I think I was on my way to France. He seemed bitter, disillusioned with the Aurovilians. It was as if they had betrayed him somehow; one could feel a very deep pain. I felt ashamed…

Most of the time though, he exuded love, and love, and love. I will always remember the last time we interviewed him on film. We were three in his little room in the Ashram nursing home. Olivier, Alain and me. We felt a bit embarrassed because we had been made to understand that bringing lots of equipment into his room was not really welcome. Olivier wanted to shoot with a good light, so we had to move objects around and arrange lamps the way he wanted. But once the interview started, it was only love. Love and gratitude. Love for Auroville, love for the Mother. His recalling of the Mother was so vivid, so strong – he remembered how she used to caress his arm – one felt that she was there in the room with us.

This book is meant to express a little of our gratitude and our love. He gave to Auroville without counting, without limits. We were grateful, of course. Of course. That went without saying – and without saying anything most of the time. Let us acknowledge that collectively we were quite stingy in our appreciation, too much embroiled in our own complications for realizing the miracle of that constant devotion. Now is the time for giving back to him.

Now is the time. Now that we know about nastiness, now that we know about arrogance, now that Auroville has learnt what it is to be trampled upon, – now at last we should honour the one whose constant concern was the protection of Auroville; we should remember the one who gave a legal status to the Mother’s project with the only aim to create “a cushion” between this fragile endeavor and the harsh political realities.

That benevolent protector, that king-teacher whose name means “the crown”, to him let Auroville give respect and love.