Auroville needs the world

Keywords: Personal sharing, Personal history, Art, Theatre, Multiculturalism, Feminism, Ecology, Early years, Contact with the Mother, Sanskrit School, Last School, Sri Aurobindo Society (SAS), Ami community, Matrimandir Nursery and Sweden

Marta

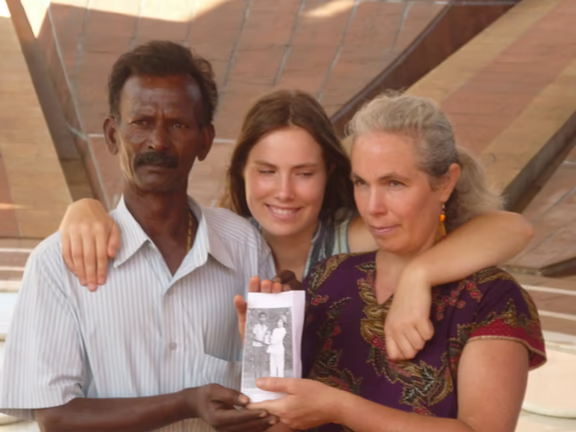

Ramalingam and Marta, embraced by Marta’s daughter Marina, holding the photo when they, as children, laid the inauguration stone of the Matrimandir

Through my work with visual arts within theatre and set design in Sweden since 1987, I’ve met a lot of people who do creative things, but I’ve also been able to work individually by taking on projects that allow me to strive for what I'm searching for. We're working with contemporary dancers and forms of performing arts that are striving for a critical point of view on society and are also pursuing expression and beauty at the same time. It's an interesting field in which one searches for something without really knowing what will emerge.

Theatre is a dynamic and intriguing realm. Over the years, the focal points have shifted every two or three years, reflecting societal trends, although themes like feminism have long been woven into the fabric of theatre, followed by emphases on ecology and multiculturalism.

Work is an all-pervasive process to me. My colleagues within the theatre sometimes ask me why I never take breaks and stop working, and I tell them that I stop only when the project is completed. It's like a cultural attitude that I took from the early days of Auroville. One sets the goal as close as possible to the vision, not to the limits of the ground reality. And this is timelessly applicable. It’s like the pioneering spirit of Auroville is alive and active in your daily life.

My family moved to Auroville in 1968. We didn't make it to the Inauguration, but arrived a few days later. I turned five that year. We had sent our photos to The Mother and got accepted. When we arrived we moved to Promesse, because at that time there was no other place to live in Auroville, but already a lot of interesting things had started happening and we were put into many learning circles.

I remember there being really very creative people around and an extreme sense of dedication and responsibility and joy. There was a strong sense of limitless possibilities, even though the limitations were very obvious. For everything had to be reimagined from scratch.

In other words, there were extreme limitations from without - yet no limitations from within. It's something I have carried with me afterwards in everything I do. We learned that if you want things to happen, you just have to make them happen yourself.

At that time, all the kids of Auroville were working at the Matrimandir and participating in the concretings at night. There was nobody telling us it's dangerous. We were all part of the big collectivity and the big movement, and there was this enormous trust and faith that everybody was doing the best they could.

In Promesse we were almost living in Morattandi village. It was a calm little village. We heard the bullock carts going home in the evenings with the driver asleep in his seat until the cart got home. The big wooden wheels of the carts rolling under the huge tamarind tree alleys – it really had its own atmosphere.

In 1972 the new Sanskrit School and Last School were inaugurated and run with all these different cultures and teachers from many countries and all over India, and each teacher was speaking his or her own language. So as we had a singing teacher who was Bengali we learned music in Bengali. And we learned French by learning mathematics! The teachers were young and enthusiastic, and included us in such a way that there was no separation between teachers and students: one really felt a comradeship.

In a similar way, one didn't feel the separation between all the different cultures and nationalities in the community. We were floating in all these different atmospheres here. Everyone brought their own world with them.

Looking back now, those first four years of organised school were years of super activity for kids and intense participation for everybody.

Then Mother died. We were still in Promesse and somebody called in the middle of the night and told us that She had passed away. So we jumped on the motorbike and went to the last Darshan, and saw Her lying there, downstairs. The whole of the Ashram was there, along with a handful of people from Auroville.

For everybody, it was a big question mark: how was this possible? It was as if the director of the play had suddenly died in the middle of the rehearsals. So what do you do then? The script was not finished: Auroville had just barely started.

For me it was an even stranger experience because since I arrived here, and up to the age of ten, I had seen The Mother quite a number of times. And I have a very clear memory that she used to laugh a lot and be really happy. I remember having done a little drawing on her lap; I drew a rooster who was drinking coffee. She laughed so much at that, she was so alive and playful and so joyful: a real person, real in the sense that we understood each other. And, in contrast, around her were all these serious people with their extreme reverence. But when she disappeared, it was not real. It was like putting a blanket over us.

When The Mother left her body, everything began to change. There were people who were trying to misuse power (the attempted management takeover of Auroville by the SAS), thinking that their truth was the only truth. And that's when things got muddled

That's what happened in 1976. The schools were closed. We kids experienced in a short time-lapse (from '68 to '76) the first rudimentary teaching circles where improvised teachers could disappear at any moment, and then organised and complex schools rich in subjects and sports with the luxurious regularity of permanent teachers, and then the abrupt ending of it all. It was never spoken about, but there had been a strong collective sense that our teachers would take the responsibility to follow us, that the school would re-open after the monsoon, but this didn’t happen. Any sense of responsibility towards the children vanished.

The day the school stopped, whatever age you were, you suddenly became an adult. Everyone was suddenly responsible for themselves. We all came out of a bubble, and understood that things can go wrong. Before, we were living a kibbutz kind of reality, where everyone is the parent, and you can turn to anyone and be at home in their home. At times, we children were staying for months in other people's homes, taking part in their lives.

From one day to the next, that was over. All the children felt abandoned.

Numerous North Indian kids that were boarding at Aspiration were sent back home. The Tibetan children went back to different places in India where they had their contacts, many local Tamil kids were faced with an ultimatum - come back or you'll be cut off from the villages - and, gradually, many foreign kids also disappeared to relatives abroad or to international boarding schools in India.

Suddenly, just a handful of children were left here.

My peers who had teachers as parents, continued being taught privately by their parents, or by correspondence, or they went to boarding schools outside. But none of that was shared. For us remaining kids, we went from community support to individual survival.

We were decimated. So after about a year, something was created for us by some adults who made a children's community. But they also left it up to the children to decide what to do with it.

When I moved in I was turning 14. My 7 years old sister Grazi joined first so I promptly followed her. There were huts and one central house with a kitchen and we had a few animals. The place was called Ami, and the children ran it. We were so tired of the grown ups because we felt that they had deceived us, so we were really happy just to be on our own. We looked after each other, we'd cook together and had ongoing collective projects like creating circus events for the community. During that time of food scarcity (as a result of the SAS freezing Auroville's funds), we only had bread and ragi and peanut oil, which we put as jam on our bread. Luckily we were allowed to eat our dinners at the Matrimandir camp Unity Kitchen in exchange for washing the dishes.

But it felt like the monsoon would last for years - and it did. I was really longing to find someone who wanted to teach me something. Wasn't there going to be another future? I always felt that my parents were so busy, and respected them for that, so I did not ask for anything. When I told them later what really happened, that I struggled, they were surprised.

I began working at a tailoring unit in the afternoons, and in the mornings I finally found back some of my old teachers who agreed to just give me a lesson here and there. We were dependent on these individual adults teaching us things, but the self-discipline to keep pursuing studies wholly depended on your own will.

Some of the kids started living very political lives, especially our friends in Aspiration. They, too, became grown-ups immediately: they were sucked into the world of what the adults were doing.

Back at our old school, there were the abandoned sports facilities: a running track, a football and basketball field, and gymnastic equipment. So that became my thing, I just threw myself into sports because it was a discipline that kept me in contact with something that I knew.

While I was in Ami, I ran every morning at 4:30 all the way to Discipline and back, then I did gymnastics. And then I went to take some lessons here and there from different people, worked at the tailoring workshop, and by 2:30 pm I would go to the sportsground again till nightfall.

This went on for four years, with nobody teaching or supervising us. I ended up doing too much, and hurt my back. The back pain lasted quite a long time, and it was then that somebody offered to take me to Europe, saying somebody could help with my back there, and, at the same time, I could see what Europe was about.

There I met an architect and his wife who was a theatre critic who discovered that I was good at drawing (thanks to making botanical drawings at the Auroville Nursery) and that I loved art. And they had a library full of art books. So suddenly I felt that I could communicate with someone, and they understood what skills I had and could develop.

The architect had studied at the Art Institute in Florence and strongly encouraged me to apply there, since I had relatives in Florence. Of course, I had no certificates, but a teacher there discovered a loophole in the rules allowing Italians over 18 to apply through an entrance exam, without having previous diplomas.

After never having left Auroville and never studying in Italian, I suddenly had to study all these books in Italian on art history, trigonometry and geometrical drawings within a month. The exam went well, I gained entry to the second year of five, and then a whole new experience started. It was such an utter relief to finally be in a structured context, learning so much. I had this amazing thirst for knowledge, and finally I had access to this knowledge and all these possibilities, and these places imbibed with culture.

I remember how visually for me seeing the cradle of the Renaissance world felt familiar. The colours of Tamil Nadu resembled the style and colours of the Italian Renaissance. And Indian women with their wonderful saris resembled these silhouettes and faces from Etruscan museums. The big golden earrings of Magna Graecia, Pompei frescoes, late Hellenistic art, all drew parallels to India for me.

In those days it was a big thing to leave Auroville, because you felt you were betraying the project, taking an irreversible step. Also, because of this whole experience of what happened in the second half of the 1970s, it took me seven years before I even just considered coming to visit. I met my family only once during those years.

I strongly felt that I had to find my own identity and my own life. On my first day at the Art Institute, as I was cycling back to where I was staying, I lost my thread necklace with my Sri Aurobindo symbol. That somehow gave me a concrete feeling that now I was doing it all on my own. Nobody was going to help me out, not even the people who had blessed me on the way.

The feeling that you have to step into fire, and that you won’t always be protected with someone holding your hand, the feeling that you have to wake up and find your own path, that’s what I learned through that experience.

After finishing my studies in Italy, I visited Sweden in 1984, because there was an Auroville International meeting there. I was very curious about Sweden because my parents, Piero and Gloria, had worked for two years in Finland, before we moved to Auroville in 1968, and often described Scandinavia positively, and during that meeting I met my life companion Johannes.

So I thought I would just check it out and see how things could work there for me - and I am still checking it out. I started working with my partner, who is a music composer, and we initially collaborated on different projects. It's quite difficult to combine our fields, because orchestral music and set design most often come together in opera commissions. Then I got other assignments, for theatre and dance performances, and I am still working in that field.

In 1992, our daughter Marina was born. And that brought flashbacks to my own childhood, wanting to share the beautiful experiences of Auroville. It brought me closer to my family, but it also brought up things from the past, regarding the immense value of education for children that shouldn't be played around with in the name of ideologies, risking to burden children's lives or disorient them.

It also reminds me of an experience I had about ten years ago, coming back here. I watched the introductory film on Auroville at the Visitors Centre, trying to be as open minded and neutral as possible. And yet, I couldn’t help but feel this is some form of propaganda, giving the message that this is the best place on earth.

I kept hearing that Auroville is the place the earth needs, but I think it is Auroville that needs the world.

We're not disconnected from the world, we are already 50,000 inhabitants with the villages around us, but we are trying to stay in a bubble that is impermeable to the reality around it. It is like multiple transparent drawings on top of each other, which, when looked at all together, show the reality, but we choose to look at only the one layer that we like.

There are fantastic things going on everywhere. The world needs to become an ecologically balanced place, that’s the most important project at the moment, and it’s just as spiritual to be able to hold hands and say things such as, the ice is melting, we are going to change that.

So I spontaneously never talk about Auroville or tell people they must go visit. Only when someone really gets to know me, the topic comes up. Maybe I don’t talk about it because the whole world is there too, and there is so much interesting stuff going on and that is a magnet in itself.

That's why it took me so many years to come back. I'm a bird you know, I fly and migrate and move. I may go back to the home island, but birds are beings of the future. They fly. They have an inbuilt orientation, nobody knows how. And there are no country borders to birds. They just fly and take seeds from land to land. And suddenly a palm tree is growing somewhere, and that's how you mix cultures. And that boundary-less freedom is so wonderful.

Growing up here I had this experience of growing up with a sense of curiosity, and I’ve carried it with me ever since.