The rise and fall of the Aura network

FeatureBy Aman Kapur

Keywords: Aura app, Economy, Economic experiments, Gift economy, Money, South Korea, Financial Services, COVID-19 pandemic and Apps

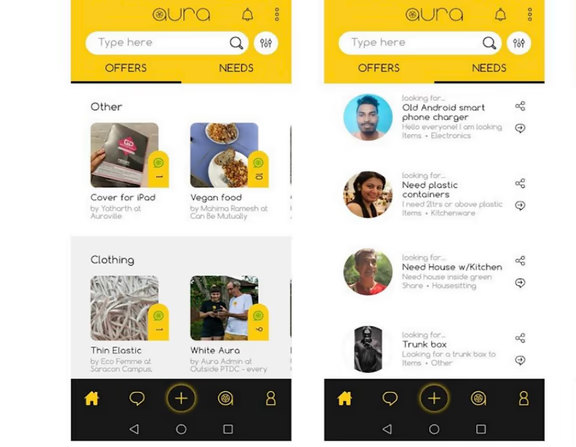

Aura app screenshots

Aman Kapur

In early 2019, Dan Be Kim, a Korean woman who had grown up in Auroville, returned to the community. Auroville had recently marked its 50th birthday; there was much to celebrate, many accomplishments, but the community was still struggling to manifest its vision of a cashless economy.

Dan Be had been studying in Canada, South Korea and Germany. Perhaps inspired by her childhood in Auroville, she was intrigued by the potential of concepts such as a universal basic income, a circular economy – and, in a broader sense, the opportunities and challenges of creating an alternative economic system that would be more egalitarian and sustainable.

Back in Auroville, Dan Be tied up with a number of other community members who were similarly interested in advancing the development of Auroville’s economic experiment. After several conversations – often over tea and biscuits/lunches – these individuals came up with the idea of creating an app that would merge the potential of technology with the possibilities of a sharing economy, and they launched an innovative project that would come to mark a milestone in Auroville’s economic history.

The Aura app (as it came to be known) was officially launched in November 2020. In its mission statement, the Aura team stated that its goal was “the conscious evolution of an economy away from an individualistic life of survival, evolving towards a life of creativity and communal harmony.”

“The vision of the Aura is to break free from the linear value cycle where goods are used and turned into waste,” the statement continued. “As the world struggles with an unstable economy, a pandemic, poverty, global warming, pollution, war and hatred; a seed of love and human prosperity can now be planted in the soil nourished by the Aura Network. An unconditional sharing and interdependence no longer remains an unreachable ideal but a living reality.”

The Aura app had some notable early successes: 350 users joined it in its first 6 months, and over 600 offers were recorded in 2021, its first full year of operation. Yet earlier this year, the app announced that it was shutting down.

Like the Aura team, like so many who have grown up and lived in Auroville, I too am fascinated by the potential of an alternative economy. I was born in Auroville and attended Transition School and Future School. In recent years, I have been studying and reading about economics, trying to understand what types of tools or mechanisms could prove useful in breaking out of the dominant economic paradigm that seems so entrenched around the world.

I found myself intrigued by Aura and, towards the end of 2021, reached out to the team to see if there was any way I could learn from their work, and maybe get involved. Everyone was very welcoming; in the true spirit of a sharing economy they were willing to share their valuable time, and also thousands of data points to help me understand patterns of usage. After conversations with Dan Be and long-time Aurovillian B, another core team member, I worked closely with Pranav, one of the main web developers, mostly doing data analysis. I also interviewed and spoke with several users.

Through this work, I came to a much better understanding of both Aura’s initial successes, and some of the contributing causes for its eventual shutdown. I feel both of these are important to understand for what they can teach us about future economic experiments in Auroville as the community continues along its search for a place, in the Mother’s words, where money would not be the Sovereign Lord. More generally, I am interested to know what lessons Aura has to offer the broader world for the possibility of an alternative economy.

The Aura app

Supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation, a part of the South Korean government, the development of the Aura app went through several rounds of wireframing, prototyping, and debugging until it was finally ready to be launched on the Google Play and Apple app stores. The app was also launched alongside a public facing web page and an admin panel, which allowed the project holders to visualise data and optimise performance.

After a user signed up, an admin from the team would then check to make sure that the user was either an Aurovillian, a SAVI Volunteer, a Newcomer or a friend of Auroville, in order to make sure that the network remained a closed community-driven project. Aurovilians were the primary users of the network, making up more than 70% of the user base. SAVI Volunteers made up 17% and Newcomers made up 11%.

The user interface was designed to facilitate the exchange of goods and services within the community. Upon joining the network, users could create profiles, list items or services they were willing to share or exchange, and use an inbuilt messaging platform to arrange meet-ups for exchanges. The app utilized a point-based system that gave credits to users on a regular basis, and users could also gain points by offering items or services. Points could then be “spent”– or traded in the language of a sharing economy – for goods or services from other members.

Initial successes

As noted, the app found early traction in the community, and its underlying goals seemed to resonate with Aurovilians’ desires for a different kind of economy. One user named Luke stated that “I came to Auroville because I wanted to live in a place that looked at economics and community differently. I see Aura as portraying exactly this … This is exciting.”

Laure, another user, said that “My experience with Aura is great and very inspiring…I enjoy it being based on a currency which seems more fair than money in my opinion. The Aura is far beyond the concept of money.”

One of the main drivers of the app’s success appears to be the way it built on and strengthened existing bonds of community. Archana, a user of the app and a newcomer, said that “just being on the Aura Network for a month and a half has allowed me to know many people. Many more connections. It’s amazing.” Another user I spoke with, who asked to remain anonymous, said that the “social aspect of the network fosters community and allows me to make new friends.”

The sense of community was heightened by the large number of services. Almost 40% of the activity on the network was constituted by services, which allowed residents to interact with each other and share their skills and knowledge. Among the services offered were the opportunity to learn a language, gardening, and to cook. The exchange of services brought people together, promoting interaction and collaboration, while allowing for personal growth.

Aurovilians have often subscribed to a culture of more conscious consumption, prioritising the reuse and repurposing of items over constant acquisition. This aspect also drew people to Aura, as the network played a pivotal role in promoting resource sharing. The community embraced the concept of a circular economy, an idea based on reuse and regeneration of materials. Amy, a particularly active user, said that the network “allowed me to look at my life and see what I can offer. I look around my home and identify objects that I no longer use.” Items, such as clothing, furniture or tools that might have once been discarded found new life through sharing. All of this seemed very much in line with the project’s stated goal to “create a space for a circular economy where things considered waste, or things that are not being proposed can be identified and then upcycled and repurposed.”

Limitations – and shut down

By the middle of January in 2021, the network was being used by over 25 people on a daily basis and on some days witnessed more than 30 exchanges of goods and services. Yet, on June 15th of 2023, the Aura project holders put out an announcement stating that the “epic experiment” was coming to an end. What had happened?

The end may have appeared abrupt. But based on the research I conducted, I believe the project faced several obstacles from its very inception. Some of these it was able to overcome; many it was ultimately unable to.

Some of the challenges were technical in nature. From the early days the team encountered difficulties, such as lags in uploading new entries, which misled users to think that the network was smaller than it actually was. In addition, the chat feature repeatedly crashed, making it difficult to sustain the community that was building around the project. At least one user I spoke with complained that the app could be very slow and difficult to use.

Some users I interviewed also pointed to the complexity of the points system as a contributing factor in lowering usage of the app. “I think the system of the points did not work well,” said one user who emphasized how much she otherwise appreciated the app and the team’s efforts. This user also suggested that part of the reason the network didn’t flourish was because it still represented a form of “materialism,” in which the points were just another version of money – one that was far more cumbersome and limited in scope than traditional currency. She compared the use of points to Auroville’s Financial Service system, where traditional money is still circulated even if the community doesn’t call it by name.

Based on my research, however, the main obstacles were not intrinsic to the app itself. One of the main issues was the challenge of what one user characterized as “freeriders.” As the number of users increased to over 450, requests or needs began outnumbering offers by 507 to 255 listings – almost double the amount. Freeriding can be characterized as the problem of users who take without giving back, exploiting the generosity of others and disrupting the equilibrium necessary to build a true sharing economy. Of course, this problem has nothing to do with the app itself but stems from a more general social dynamic within the broader community.

Freeriders also caused bidding wars on the platform, which went very much against the spirit of fairness and reciprocity at the heart of the project. These issues degraded the quality of interactions on the network and discouraged some participants. Several participants I spoke with suggested the need for filtering participants – what one person called “user control” – to maintain the quality of interactions. This would, however, cause its own problems, notably worsening the difficulties the network had in scaling up.

The app also had the misfortune of having to ride out two major crises in the Auroville region: first COVID, followed by the social divisions that have overtaken Auroville since the end of 2021. The launch of the app was delayed by pandemic restrictions, and those restrictions continued to impede in-person meetings and exchanges necessary to sustain the network. In one of their reports, the organizers lamented “the pall of COVID restrictions” hanging over Aura.

One seeming ray of light that emerged from COVID was the broader move towards cashless transactions in Auroville, and India at large. However, the app was unable to build on this possible opportunity as virtually every aspect of the Auroville community was soon shaken by the rancor and divisions that overtook the community following the events of December 2021. This conflict distracted both organizers and participants on the network; it also broke the bonds of trust and solidarity that were central to the network’s early successes.

One final point is important to make. An app like Aura exists within a broader economic and social ecosystem, and its success hinges on its ability to effect change within that broader context. Yet, as several people I spoke with pointed out to me, the central role of money within Auroville is now deeply entrenched, and it is, of course, even more deeply entrenched within the broader Indian ecosystem. Users pointed out how these realities limited the scope of Aura, for example by preventing the ability to use the app for everyday transactions such as paying bills, taxes, or purchasing everyday items not available on the network.

As one lady who used the network said to me: “Never say never, but now we still live in a money-ruled world and consciousness. The time will hopefully come when we start giving and sharing more… but that’s a long story.”

Lessons and Implications

By the end of 2021, around the time Auroville’s conflict was beginning, there were almost 500 total users but only about 2% of them were active. It took more than a year for the network to officially shut down, but signs of trouble were apparent as almost no transactions took place in the last two months of 2021.

Without exception, the users I interviewed for my research praised the idea and the team behind the project. They saw it as an important and creative experiment, one very much in line with Auroville’s ideals and the effort to create economic transformation in the bioregion and beyond. As one user told me, “It is an experiment and we must keep on experimenting to rely less on cash.”

Despite this enthusiasm, what are the lessons we can draw from the app’s eventual shutdown? In my opinion, the key lesson is that innovative ideas and technology are not enough to bring about radical change. Ultimately, any app (or similar project) is only as strong and effective as the social context which it operates in. This point came out in multiple ways from virtually everyone I spoke with.

One concrete idea suggested by a woman I spoke with was the need for greater outreach to the community. This kind of outreach could help build awareness both about the app itself but more generally about the possibilities it offered and the benefits of broader economic transformation. In other words, the Aura app was a noble project but should be seen as just one component within a larger process. B, one of the founders, said that “It’s [Aura] not going to solve all the problems of Auroville. It’s just one more step.” To build on this stepping stone, it is essential to take stock of the experiment – what worked and what didn’t. That was my goal in doing this research, and writing this article.

In June of this year, the Aura team announced that their “epic experiment” would be shutting down on August 15th. “The Auroville journey to go beyond debit capitalism has been unsuccessful,” they wrote. “Money still remains temporarily a Sovereign Lord here as elsewhere. But the collapsing global empire is rapidly turning to digital currencies, and the consequences will soon be evident.”