Sri Aurobindo and the Earth’s Future

Art reviewBy Alan

Keywords: New publications, Films, Sri Aurobindo’s life, Paintings, England, Alipore jail and Filmmakers

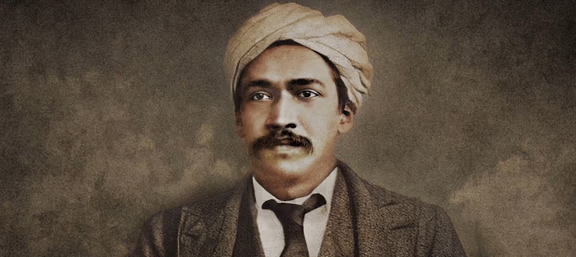

Illustration of Sri Aurobindo

There are two main challenges to be faced by anybody who wishes to present a life of Sri Aurobindo. Firstly, there is the danger of misunderstanding Sri Aurobindo for, as he put it, his life “has not been on the surface for men to see”. Secondly, there is the danger of hagiography, of presenting Sri Aurobindo as a model of perfection, a fully realised soul almost from birth, which ignores or downplays the many struggles which he underwent in his life and spiritual evolution.

Olivier Barot’s new film, ‘Sri Aurobindo and the Earth’s Future’, which was premiered in Auroville on 15th August, avoids both these pitfalls by, on the one hand, quoting liberally from Sri Aurobindo’s words about himself, and, on the other, adopting a factual rather than a hagiographic approach to the events of his early life. This film only depicts the period from Sri Aurobindo’s birth until his arrival in Pondicherry. Part 2, ‘From Death to Immortality”, which will depict his subsequent life, has yet to be made.

The film is beautifully presented. The images, which include contemporary photographs as well as modern illustrations by Aurovilians, allow us to immerse ourselves in the different periods of Sri Aurobindo’s early life. I was particularly struck, for example, by the contrast between the Himalayan vastness's of Darjeeling and the mean streets of smoky, cotton mill Manchester, which was such a shock for a young Aravinda Ghosh newly transplanted to England for his education by his anglophile father. (“I saw a world stripped of beauty.”)

The contexts and textures of Sri Aurobindo’s early life are further enhanced by the pacing of the film, which does not hurry us through the significant moments in his early life but allows us to fully enter into them. In this context, one of the highlights of the film is the extended section on his experience in Alipore jail, which allows us, almost moment by moment, to experience both the initial shock and despair of his solitary confinement in a 9 foot by 5 foot cell, and the subsequent inner education and spiritual liberation which caused him to rename his prison the ‘Alipore Ashram’.

Olivier’s film was over three years in preparation [see more on this in AV Today no. 409 eds.] and involved a great deal of research, so even the most knowledgeable students are liable to encounter new information. I was surprised, for example, by the influence of Ramakrishna upon the young Aurobindo. The film also clarifies very well how Aurobindo developed his interest in yoga and how this fed into his revolutionary activities.

This is a fine film, by far the finest I have yet seen on Sri Aurobindo’s life. Olivier now has the even greater challenge of illuminating the silent yet cosmically important work of Sri Aurobindo’s Pondicherry years. For while his active involvement in politics may have ended with his departure to Chandernagore, Sri Aurobindo continued to work upon world problems behind the scenes, particularly during the Second World War when he exerted his spiritual force in support of “a Truth that has yet to realise itself fully against a darkness and falsehood that are trying to overwhelm the earth”.