Acquiring and protecting the lands. The views of the Land Board

Editorial — By Carel

Keywords: Land acquisition, Funds and Assets Management Committee (FAMC), Land Board, Financial challenges, Working groups, Governing Board, Acres for Auroville (A4A), GreenAcres, Promesse community, AuroAnnam farm, Aurobrindavan community, Annapurna farm, Service Farm, Ousteri lake, Land exchange, Green Belt, Pondicherry-Tinidivanam Highway and Speculators

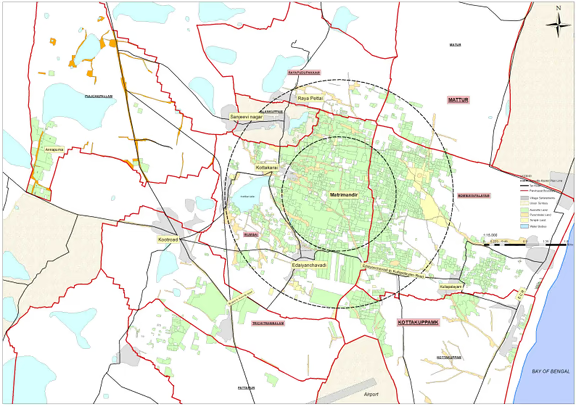

1 Approximate map of Auroville and the surrounding areas. In green are all the lands owned by Auroville. In the inner circle, the city area, most lands are owned by Auroville, but this is not the case in the outer circle, the Greenbelt

Land consolidation issues

The Land Board’s foremost task is to consolidate the City area of 1,212 acres. Excluding the peramboke (government owned) lands, about 120 acres still need to be acquired. “But a good 100 acres may not be available for purchase,” says the Land Board, “as they are disputed and/or undivided family lands.” In India, every descendant has a share in the ancestral property, but this sometimes leads to intra-family conflicts and a barrage of court cases that can take decades to get resolved. Though many people would like to sell, they are prevented from doing so by their family situation. “We may as well forget about purchasing these 100 acres in the immediate future,” states the Land Board.

The remaining 20 acres are owned by people who have no cash flow problems and hence have no reason to sell immediately. Such land owners prove to be a huge challenge for the Land Board, because they try to push up prices with threats to develop their lands into residential areas. Private residential development by outsiders within the City area would naturally be detrimental to the development of Auroville in accordance with its Master Plan.

In the Greenbelt, the area surrounding the City, Auroville needs to acquire around 1,800 acres. Here, many lands are for sale as the third generation village land-owners have moved from farming to employment to entrepreneurship. Many consider selling to Auroville a clean process, contrary to selling to outsiders which has often resulted in villagers being cheated. Nowadays, many villagers approach the Land Board for help in resolving intra-family problems or problems with outsiders. They look upon Auroville as an organisation that can assist with law and order and provide arbitration.

But how can Auroville respond to offers of purchase? For funds are in woefully short supply, notwithstanding the remarkable fundraising successes of the Acres for Auroville and the Green Acres campaigns. These successes have led to the purchase of some essential pieces of land; but looking at the overall requirement, they are but small steps on a long road.

The obvious solution would be to sell outlying lands and use the proceeds to buy lands inside the City and Greenbelt areas. Much of the outlying lands are to the west of the Pondicherry- Tinidivanam Highway and were bought in 1960’s as the Auroville township was originally located along the highway. The Auroville community has approved 23 outlying areas to be sold or exchanged. But in accordance with the Auroville Foundation Rules 1997, land sales require the approval of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Auroville’s nodal ministry, which has been requested many years ago. The request is still pending. This is detrimental to Auroville’s development because the land prices within the Auroville township area are rising exponentially, yet the prices of these outlying lands are not increasing at the same rate.

Land exchange

In the meantime, the Land Board’s solution is land exchange. Here it follows a priority approach, based on three criteria. The first is whether the land offered allows for the development of the city, the farms or forests. A second is whether the land offered would consolidate Auroville lands that are located in the midst of non-Auroville land. The third criterion is whether the lands offered are of strategic importance and can serve as deterrent against unwanted development within and around the Auroville township area.

But not all land owners in the Auroville area want to exchange their land for Auroville’s outlying plots. People from the nearby villages, as a rule, do not want to exchange their land for far-outlying lands unless those lands would have a commercial value, which is the case when the land borders a road. Auroville has a few outlying plots that have high commercial value, such as at Promesse, Auro Annam, Aurobrindavan, Service Farm, and Annapurna. Other distant plots, such as those near the Ousteri Lake, have no exchange value.

But when the Ministry finally gives permission to sell outlying lands, much more can be done. The permission will moreover allow the Land Board to increase the cash flow by borrowing internally against future land sales. But the Land Board cautions that even after permission is granted by the Ministry, it will take at least a year to come up with an endorsed process that will ensure that Auroville land sales are compliant with government procedures for accountability.

What if the city lands cannot be acquired?

Consolidation of the lands in the city area is the community-endorsed priority, but the Land Board is not exclusively focused on this as they are convinced that all city lands will eventually become part of Auroville. The Board believes it may take time, but it will happen.

But wouldn’t this block the manifestation of the city? The question was asked in the Land Board’s interaction with members of Auroville International (AVI) who visited Auroville at the end of last year. “How many strategic plots not owned by Auroville prevent the development of the city?” asked the AVI members. They were stunned by the answer: none. The Land Board is convinced that Auroville can develop and build the city for the next 10 years before there would be any standstill caused by non-ownership of a plot of land. “The non-ownership of some lands is no issue at all. The problem would only occur,” says the Land Board, “if the Galaxy Master Plan would be imposed as an unchangeable yantra [a holy geometrical diagram, eds.]. If all stakeholders can be flexible, the Master Plan’s three circular roads and twelve radials could all be put in place without purchasing a single acre. The circular roads would not be exact circles and the radials would not be strictly where they are planned today, but Auroville, without owning all the lands, could develop a township of 50,000 people within the city area, have four-storey buildings and still have more than 50% of the total area green.” This, says the Land Board, is how Auroville should develop. “For if Auroville would not seek to rigidly impose the Galaxy plan as a yantra, all land speculators inside the city area would have the rug pulled out from under their feet.”

Exchanging farm lands

The Land Board’s land exchange proposals are decided by the Funds and Assets Management Committee (FAMC), which of necessity has to take the views of the land stewards into account. But most land stewards, who have been looking after their plots for years and have made significant investments, object to the exchange. The Land Board often feels frustrated that there is no shared vision with the land stewards and the working groups, facilitating the land consolidation for Auroville.

For example, quite a few plots of top-quality farm land in the Greenbelt area are currently being offered for exchange. If Auroville had clear procedures, based on measurable criteria for evaluating farm land that is proposed for exchange (such as its soil quality and the extent to which its output is benefiting the community), and compare that to the potential of the land which is offered, the process would be clean and transparent. But this is not the case. “What usually happens,” says the Land Board, “is an emotional exchange of views between individuals and between working groups, and often the end result is not in the best interests of the community.”

The Board cites the Brihaspati land as a case in point. About half of it is located in the Greenbelt along its outer border. The other half is outside the Master Plan area, close to a highway. One part of the land is used as farm, one part for the activities of the Red Earth Riding School, and a third part is residential. The Land Board, considering the high value of the outside land, the poor quality of the soil, the lack of sufficient water, and its location close to the highway, proposed to exchange it for more fertile land within the Greenbelt area. This proposal, which would moreover consolidate a part of the Greenbelt, was objected to by the Aurovilian steward. The Farm Group, agreeing that Brihaspati farm is currently not operating at its full potential, considers that in the future it may prove to be invaluable for Auroville’s food security. Nevertheless, under certain conditions it may be open for negotiations on this issue [see the article Exchange of Farm Land on page 4]. The lack of clear transparent processes to evaluate the differing claims of the Land Board and the Farm Group leads to mistrust and hostility, and Auroville as a whole loses out.

The current Land Board also has to deal with issues that it inherited from previous land groups, which are fraught with problems largely due to unacceptable processes of these groups. An example of such an issue is the exchange of Service Farm in 2010 [see the article Exchange of Farm Land on page 4].

In the absence of comprehensive policies for land utilisation and stewardship, the Land Board feels that is on the receiving end of general mistrust from individuals and working groups. The Land Board wants certain questions to be answered by the community. What are the criteria for land allocation? Who decides on land allocation? What are the roles and responsibilities of the land stewards? And on what grounds can an individual or a working group object to land exchange? For without answers, trust and unity within the community on the issues of land acquisition and exchange cannot be achieved.

Protecting the lands

Another important activity of the Land Board is land protection, a responsibility it shares with the Working Committee and the Auroville Security team in relation to matters on the ground. When matters go to court, the Auroville Foundation becomes involved. The Governing Board has accepted the Land Board’s recommendation to employ highly qualified lawyers experienced in land matters to protect the lands and to counter any impression that ‘Auroville lands are for all to use’ and speculator’s views that ‘Auroville is an easy and soft target’. Legal action is now undertaken by Auroville against land grabs, document forgery, and the shifting of fences. The Land Board says that high lawyers’ fees are nominal in respect to the value of the land that we may otherwise lose. Furthermore, these lawyers help establish Auroville’s credibility that it will now fight to protect its lands.

Protection and village issues are interconnected as Auroville is the single largest land holder in the area with kilometres of boundaries with private and village lands. There are tremendous pressures of encroachment, creeping fence shifts, and sometimes the ganging-up of disgruntled villagers. A recent conflict with one of the neighbouring villages started with its objection to Auroville undertaking fencing to stop further encroachment and reclaim about four acres of land that had been encroached over the years. Agitated villagers then blocked access to Auroville and threatened individual Aurovilians. The conflict was calmed down with the help of the Superintendent of Police, but the issue of how to improve Auroville’s relationship with the village is still on the table of the Working Committee.

If we don’t act to protect our own land interests, it is likely that it will be squatted. But are there ways in which Auroville can protect and develop its land that also supports its relationship with the villagers and respects their needs? This is the larger challenge in our aim for embodying a living humanity unity.