A sharing economy in Auroville?

FeatureBy Manas

Keywords: Sharing economy, Alternative economy, Consumption, Natural resources, Free Store, Library of Things (ALOT), Shared Transport Service (STS) and Earth&Us

The Auroville Library of Things

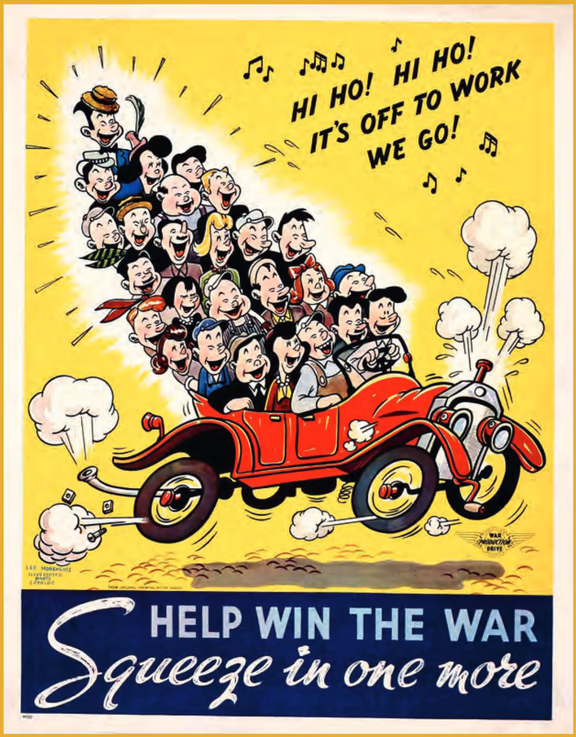

A 1940's poster promoting ride-sharing in America

For some people, this new phrase is a contradiction in terms. Much like sustainable fashion the sharing economy seems to be a forced union of two different value systems. On one side is the idea of sharing. And on the other side is the idea of exchange. However, economy as an exchange is a relatively modern idea. The word economy has its roots in the Greek words oiko, which means house, and nomos, which means rule or law. So, the origin of the economy is in the sharing of household resources among family members and close relatives.

Like any new idea, there are competing concepts, theories and labels. From the confusing label of “collaborative consumption” to the pejorative term “hippienomics,” the field is wide open. Among these ideas, the larger concept of a circular economy seems to be gaining currency. The circular economy “entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources and designing waste out of the system.” Sharing is one of the elements of such a circular economy.

Sharing has always been common during times of scarcity. The community gardens we find today in Germany, Austria and Switzerland started as shared spaces where people could grow their own food. This started in the mid-19th century when large scale migration took place from rural areas into cities and food was scarce. Similarly, when there was a scarcity of petroleum in the United States in the early 1940’s, the petroleum and rubber conservation campaign promoted ride-sharing using innovative posters and advertisements. How different is this from current ride-sharing systems, such as Lyft? Is it merely the use of modern technology to solve an old problem?

Not so, according to Min, who is experimenting with sharing systems in Auroville. “Services such as Uber or Lyft are not sharing systems but are rental systems,” he says. He is probably right – the economic morality of sharing for a fee and the idea of sharing for free are two entirely different things. There is growing criticism about using words that generate the feeling of “sharing is caring” to generate huge profits. According to one critic, the meaning of sharing should be “wrestled back from the jaws of those using it to profiteer.” But it might be a little late for that. There is much excitement in financial markets about the so-called sharing economy. And for good reason too – Airbnb averages 425,000 guests per night, nearly 22% more than Hilton Worldwide. Price Waterhouse Coopers estimates that the sharing economy will be worth $335 billion by 2025.

Of course, there are examples of companies that provide true sharing services. For example, you could subscribe to Love Home Swap, and swap your home with a family from across the world. The two parties pay no rental, but merely exchange their homes for a limited time. It’s turning out to be a wonderful way to travel, especially for families on long vacations. And there are other companies that make a profit but do it for a worthy cause. One such company is Cohealo, which enables hospitals to share underutilized equipment among themselves.

This idea of sharing idling capacity is at the core of a sharing economy. The capacity could be spaces, such as homes and offices. It could be products, such as tools and toys. It could even be knowledge and skills. Looking at sharing through this lens, Aurovilians have been sharing resources for a very long time. House-sitting is an established Auroville practice and is mostly done without any exchange of money. Sharing of office spaces is less common but might become more prevalent as more and more work moves to paperless offices in the “cloud.” It is also possible to think of ways to share underutilized spaces, such as spaces in schools after class hours.

The Free Store and the Library of Things

The Free Store is another good example of sharing. Many Aurovilians get their clothes entirely from the Free Store and are even able to cycle through fashion seasons! The Auroville Library of Things (ALOT) started by Min is another example. But ALOT seems to be a little slow in taking off. Located in a container across from Solar Kitchen, it looks a little desolate. Few people step in to see what is available and fewer still borrow anything. The most commonly borrowed items are kitchenware and ceramics. Only about 50 Aurovilians have used the service ever since it started.

One factor for this low usage could be the limited number of products available for borrowing. A library of things, just like a library of books, needs to have a large number of items to be attractive to users. This, in turn, needs either extensive sharing of “things” by Aurovilians or money to buy products to stock in the library. Sharing has been limited and ALOT really does not have the financial resources to buy things.

Another factor to keep in mind is the difference between donating what we no longer need and sharing as co-ownership. ALOT was started with the idea that people would gladly share what they own but don’t use very often. So, you could co-own with the community the step ladder that you use only occasionally. This is quite different from giving away your child’s old picture books. Perhaps people are less willing to co-own and more willing to donate. This changes the nature of the items that are available for lending.

Shared transport service

The other relatively new initiative is the Shared Transport Service, also initiated by Min and his team at Earth & Us. This service is working well – it has an easy to use online booking system, but you can always talk to a real person if you need special attention. There have been challenges, though. The taxi service that originally partnered with the Shared Transport Service backed out after a few months. The second taxi service had to withdraw after they received threats from taxi operators who feared that their profits would take a hit with ride-sharing. Currently, the service is run with independent drivers who are not employed by any taxi service.

Interestingly, Aurovilians continue to post taxi sharing notices in News&Notes and on Auronet, even though there is a well-managed service that works fairly well. Perhaps this points to an Auroville-specific reason why ALOT and Shared Transport have not scaled as quickly as planned. This reason is the suspicion of anything that is centralised. It will be interesting to see what happens if house-sitting, which works through informal networks, is organised through a centralised online application. I suspect the people who are looking for houses will be thrilled. But I am not sure stewards will use the system as much.

House sitting is also a special case because the house is maintained and looked after when it is shared (except in some rare instances when stewards return to find their home in shambles). How easy is it to share other products? It’s one thing to share something that you don’t need any more, such as an old toy. But what about a power tool? If you care about tools, how easily will you share them, knowing that they might be used by people who are not trained or who might not care as much? According to the Nielson Global Survey of Sharing Communities, 23% are willing to share power tools, but only 17% are willing to share furniture. Another study asked people to rank their willingness to share different things on a scale of 1 to 5. Experiences (such as travel tips) came in highest at 4.7. Other items at the high end of the scale were ideas, books, tools and services. Homes, clothing and bed linen all ranked fairly low at 2.7, while sharing a toothbrush, understandably, came in last at 1.4.

These surveys show that, more than anything else, people are willing to share their knowledge and skills. While some informal sharing of skills does happen in Auroville, this is one area which might benefit from an organised sharing platform. It could range from something as involved as setting up a grey water recycling system to something as simple as helping someone with their school work.

At the bottom of all this is a set of values. For Min, these values are centred around sustainability. “The reason we started the Library of Things and the Shared Transport Service is to help reduce consumption and thereby reduce industrial pollution and the use of finite natural resources,” he says. Do Aurovilians in general share these same values? It’s hard to say given the wide diversity of lifestyles in the community.

For many others, sharing is about living a simple, frugal life. For them, sharing is natural, while ownership and accumulation are perverse. This philosophy has a long history, from Socrates and the Buddha to the idea of a gift economy. Many young people in modern affluent societies consider ownership to be a burden and believe that sharing will build stronger communities.

On the other hand, human civilization has always celebrated extravagance as a sign of high culture. Whether it’s the Sistine Chapel or the Taj Mahal, our markers for periods of great cultural progress are opulent, and some would say wasteful, buildings. Can the idea of a simple life coexist with the need to leave a legacy? This question is particularly relevant in Auroville today, when there is renewed focus on building the city. And what did Sri Aurobindo mean when he said, “a simply rich and beautiful life for all”? Did he mean richness in wealth, or did he mean rich in experiences, ideas and expressions?

Growing the sharing economy will not be easy in Auroville. Our differences and diversity is likely to remain our weakness when it comes to changing the way our economy works. Perhaps we will be forced to choose a sharing economy – and a simple, frugal life – when we see that it is the only way to sustain ourselves and protect our fragile ecosystems.