Life in Kottakarai: reflections on an early Auroville community

FeatureBy Daniel Brewer, Andrea van de Loo, Lisbeth, Binah and Gordon Korstange

Keywords: Village relations, History, Auroville history, Bioregion, Villagers, Aspiration community and Auroville International (AVI) USA

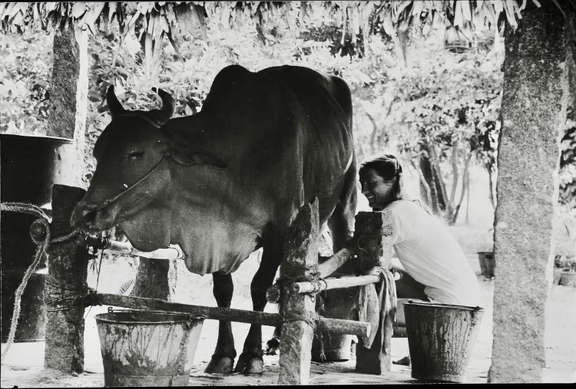

Lisbeth milking a cow

How Auroville Kottakarai began

by Daniel Brewer

Daniel Brewer, born in Southern California in 1938, traveled overland, arriving in India in 1969. He made Auroville his home for the next 10 years. He has lived in Mexico for the last 22 years.

Before the move to Kottakarai, those of us living at Silence community were informed that we were living on the future site of the Indian Cultural Center, Bharat Nivas, and we would soon have to relocate. With an open heart, and a number of AV property maps, a small group of us set out to find a home for our community.

Since Auroville had many plans for the future, we realized that if we located near a village, we might not get moved again.

We wrote to the Mother asking for permission to live in or near a village, specifically Kottakarai. We felt that locating right next to the village was a good idea. This was an unusual request, a unique request, coming from velekaras (white people).

When the Mother did give us her blessing, as members of Auroville, she encouraged us to be humble. She said that villagers were innately more spiritual than us, and that we as Westerners shouldn’t think we knew more than them, and we shouldn’t be egotistical in our thoughts or activities, feeling proud that we were doing so much to “help” the villagers. I remember feeling very moved by this.

Kottakarai 1973-1978

by Andrea van de Loo

Andrea arrived as Angela in Pondicherry in 1972. She lived in Auroville, first at Matrimandir Worker’s Camp then in Kottakarai till February 1978. For several years she ran a small first-aid clinic in the village of Kottakarai. In Santa Cruz, California, she became a certified practitioner of polarity, acupressure, Reiki and hypnotherapy.

From Kottakarai, you could, in those early days, look over the vast plains of barren red earth all the way to the Matrimandir. Halfway between Kottakarai and the Matrimandir, along the dusty path, were two small jungle groves which had been saved from the general devastation of villagers cutting firewood, their goats and the torrential monsoon rains, because these were temple lands. In the one closest to the Matrimandir, the Kali temple was located, a low rectangular structure with a black iron gate, no windows and a statue of the goddess in the back. The grove nearer to us was considered Kali’s house, home to a gigantic cobra. It was in the shade of the tall cottonwood trees of Kali’s house that Daniel had built a hut for himself.

Into this community, I was warmly welcomed. A simple octagonal bamboo hut out in the fields was available for me. It had a dirt floor with a few mats, a small dresser and a simple cot with mosquito netting. It provided me a peaceful space to make myself a temporary home.

The community was situated just across a canyon from Kottakarai village, which consisted of simple homes made of mud walls and palm leaf roofs, haphazardly placed around a village square. The grandfather of Radhakrishna, one of our friends in the village, had planted a tree there many years ago which now offered a huge canopy of shade for all to enjoy. Walls and floors of their huts were regularly rubbed with a paste of fresh cow dung mixed with water to disinfect and clean the simple dwellings. It smelled delicious. The village had a temple but was so poor there was no Brahmin priest to tend to it. Auroville at large employed quite a number of the villagers, the men mostly for labour, the girls and women for housework, child care and handicrafts.

When you came to live in Auroville, you let yourself be guided by what was true within you. Nobody told you what to do or where to go. You found your work by expressing your natural inclinations and allowing yourself to be led to wherever you happened to be drawn. In that surrendered state, things just seemed to flow. Small miracles became everyday fare.

I started by going out into the fields to weed around the newly planted trees. After the bustle of the Matrimandir workers’ camp kitchen, I worked in blissful solitude, enjoying the quiet, the heat, the critters. Lisbeth and I took care of the food distribution from a small storage room, where we would receive the foods which came by bullock cart from Pour Tous, Auroville’s distribution centre in Aspiration. We would divide the foods into baskets for each individual or family amongst us.

Andai Amma, the old lady who lived in a hut next to the Banyan Tree when the construction of the Matrimandir began, had moved back to the village. We all felt that she was in touch with the occult. She lived like a shamans on the outskirts of Kottakarai. She had three sons. Rajili and Vijayrangam were hired as watchmen. Both brothers clearly felt a spiritual connection with Mother and were aware that Auroville was Her creation. Vijayrangam would often go around and mark our foreheads with ashes and red paste from the temple, all the while murmuring sacred mantras. Then, there was Murugesan. Such a fine and kind man. It reminds me how Mother said that the Tamil villagers were the first Aurovilians.

Together with them, hundreds of holes were dug, trees planted and bunds built up around the fields to keep the monsoon rains from running off and eroding the soil. Once a week a large green water tank mounted on a bullock cart was drawn by Morris, our bull, through the arid fields. We would fill bucket after bucket and carry these to the young trees to water them.

We had a rather primitive community kitchen in the Palmyra grove. One day a boy from the village came limping in, crying. His knee was bleeding. Using a small first aid kit, I cleaned and bandaged his wound. I got a big smile in return and off he went. The next day he came back with a few of his friends, some of them with infected sores, others with scabies. I treated them all from my little box. This eventually led me to open a small first aid clinic in the house Constance had built in the village, where he no longer lived. Radhakrishnan came to help me, and over the years we treated over 4,000 villagers coming in on foot from far and wide. I would like to write a separate story about the clinic!

I was impressed by Daniel’s gracious relation with the villagers. Tamil is one of the oldest living languages on the planet and exceedingly complicated. Daniel spoke Tamil with surprising fluency, even able to make jokes. Besides being involved with planting trees and care of the land, he had become the local cobbler. He was making handsome leather sandals for any and all who needed them, including the villagers who were quite amazed that this velekaran would stoop to a work that was normally only done by Harijans, the outcastes. Small wonder that the villagers adored Daniel. We couldn’t have had a better ambassador for Auroville in the village of Kottakarai.

Kottakarai 1977-80

by Gordon Korstange

Gordon Korstange lived in Auroville during the 1970’s. He is the editor of Connect and lives in Saxtons River, VT.

We came to Kottakarai from the fury and flux of Aspiration that had brought about the closing of Auroville’s first school where we had worked. What we found was a quiet greenbelt community, close to the land, which had taken the name of the village nearby as a gesture of unity...

At first we were somewhat disconcerted, staying in one room of a cleared out workshop, a hastily built open air bathroom next to it with thatched walls. It was the greenbelt after all, not the town, but in those days almost all Aurovilians lived similar lives cloistered under thatched roofs. So we adjusted, we stayed.

When we arrived there were almost 30 members of Auroville Kottakarai, most of them Dutch and American with some Kottakarai Tamilians.

While Jeanne worked in the Matrimandir nursery, I attempted to help Jaap and Daniel with tree planting and other agricultural activities. There were fields of red rice and local grains, cows, a tree nursery. Both of them spoke fluent Tamil, which meant that it had become the main language of communication among community members. It was here that I finally became confident in speaking Tamil.

I also learned to milk cows and plough a few furrows in a field, to use an alangu (long crowbar) to break open the hard red earth in order to create a huge open hole, to be filled with enough compost to nourish a single spindly sapling, a lone splash of green rising above the red earth. It often had to be replaced, the victim of voracious goats. Like other greenbelt communities, a wadai (gully) ran through it, carrying monsoon rainwater and red dirt. The trees helped to hold soil from being washed away.

I wrote a lot of poetry.

We lived closely with the Tamil villagers. Twice a week I walked to the road and took the afternoon village bus into Pondy for a lesson in Carnatic music. The bus was always jammed with villagers going to market, often to bring things to sell, like chickens or vegetables. It would stop just outside Kottakarai and the abrasive conductor would take ten minutes to sell tickets, constantly trading insults with the passengers.

One evening, Kuppusami the watchman turned up with some friends to borrow an oil lamp so they could go out into the fields at night to hunt bandicoots (“pig-rat”), large ugly rats that provided protein.

Whenever we came back to our workshop home we would pause at the door to allow time for scorpions to scatter from the open floor. We learned to proceed with caution before reaching into any confined space in that dwelling…

It was a small world unto itself. Roy was building a Japanese-style pottery; Larry, Sundaram and others were baking bread early in the morning; and occasionally the motorcycles of Aspiration would swarm down the road, engines roaring, on their way to some meeting, leaving behind dust and uneasy quiet.

At Pongal we all gathered in the cow shed to sit on the floor and eat off of banana leaves while the animals looked on…

The days were scorching. The nights were enchanting. The Milky Way arced above our paltry oil lamps. It was so dark that the Southern Cross constellation could be seen hovering above the lackluster lights of Pondicherry. The sea breeze roamed over the barren lands of Auroville all the way to our hut, bringing the cries of jackals from the wadai. Above us rustled our silk-cotton trees.

Dosai Amma

by Binah Thillairaja Binah

Binah Thillairajah grew up in Auroville and moved to the U.S. to pursue a B.A. and M.A. in International Development. She currently serves on the board of AVI USA and lives in Denver, CO with her husband and kids.

I was a child in Kottakarai with the same birth year as Auroville, running barefooted down the dusty dirt paths. The wind whistled through the casuarina trees of the forest and Dosai Amma’s one room watchman mud hut perched at the edge of the trees.

Dosai Amma? She must have had a different name once, but if she did, I never heard it. To my young eyes her wrinkly chapped skin was older than the trees. Her eyes twinkled under a sparse head of hair and her ear lobes hung low with bolts of gold, her life’s savings right where she could touch them. She always seemed to wear the same brown sari in the style of a widow with no blouse.

Dosai Amma shouting out to me in Tamil in greeting… ‘come eat.” Dosaiamma who made meenkorumbu, vegetable sambar and rice in mud pots on her small wood stove fed by sticks from the forest.

Dosai Amma who would pick the best pieces of fish out for me and set them on my plate with a toothless grin.

In front of her one room hut was a tiny porch and fire place fashioned of mud and sani (cow dung) where we sat some evenings talking and eating. Perumal and I would perch on the edge of the porch and laugh as she complained about her aches and pains. We would eat, throwing the fish bones to the village dogs that patiently waited all around the hut; strays or guard dogs?

In the pitch dark of the night in the forest the only light came from a single kerosene lantern hung from the roof over us. It was quiet on her porch, with the smoky fire and her cackling voice for there was nothing else but the company, the food, the sound of the casuarinas and the dark night.

She seemed to be older then the trees and the land we stood on, and on nights when she cried drunkenly after drinking some local arrack. I wondered about who she had been before she was Dosai Amma – old lady of the forest?

Early Days 1970-1985

by Lisbeth

Lisbeth was an original member of the AV Kottakarai community. She continues to live In Auroville.

For those who came in the early seventies, the focus, the work laid out, was clear: starting new settlements, saving the severely eroded land by planting trees, bunding, making dams and other earthworks; starting vegetable gardens for the community; keeping livestock; trying our hand at dry agriculture, planting fields with millets, rice, groundnuts and cow fodder; learning from our close village neighbors the amazing survival skills to live in this unfamiliar dry, hot and barren tropical corner of the world.

Life was so different from today, concentrated in small settlements, simple, innocent, more intimate and related to the land where we found ourselves. Distances and life styles between Aspiration and Kottakarai, then a continuous large, vibrant community where we lived, seemed vast.

We walked and cycled, worked together with the first Tamil people who joined Auroville. There were no servants or workers; we were all working hard alongside each other (while daylight lasted.) Water from open wells was pulled out by the bucket which, through a chain of helping hands, was stored in barrels fixed on a small bullock cart to water the tree saplings we planted all the way to the Center.

The Mother was still with us and this was a great blessing, She received Aurovilians with their questions and we went for blissful darshans. She named the children born here, the names always having an Auro in it as the ‘family name’. A peaceful time it seemed -before all the strife that followed, the globalization of India, the accelerated pace which the internet brought and the chaotic world events that took place began to trickle into our awareness.

We did not move far afield, visiting close neighbors, exchanging ideas and experiments. Children were often born at home in small huts with a flickering storm lantern. They were always coming along, tough, barefoot little troopers playing with whatever was available in nature.