Kabir’s message of love and oneness

FeatureBy Lesley

Keywords: Spiritual poetry, Music, Translation, Spirituality, Indian culture, Bhakti, Varanasi / Benares, Saints and sages, Friends of Auroville and China

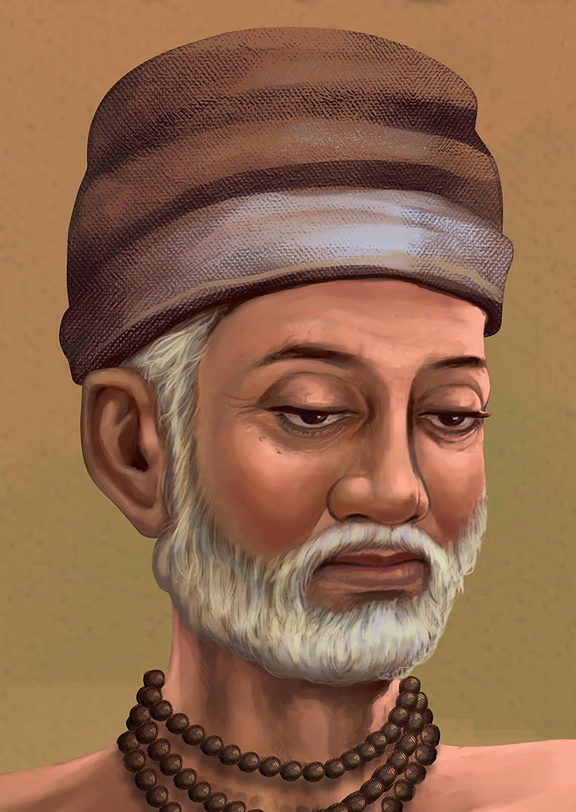

Contemporary rendering of Kabir’s portrait

Prof

Like many youngsters growing up in north India, Professor Kumar studied Kabir’s poetry at school. Later, he became a nuclear physicist and an academic in Canada. He describes how his study of Einstein led him to read the works of Sri Aurobindo, which then became part of a spiritual search that led him (back) to Kabir. Having not read Kabir for 20 years, he had “quite an awakening” at the age of 36, as he rediscovered “the depth of the verses of this completely un-lettered sage and a poet,” he recounts. “I had a reputation as a writer and an intellectual, but I learnt more from the simple words and metaphors of an uneducated weaver poet, than from the other great thinkers.”

To illustrate his point, Professor Kumar bursts into a Kabir couplet, first in Hindi and then in his own English trans-creation:

On the crossroads of life

Kabir stands

With a raging flame

Of love

In his hand

O dear friend

If you seek to follow me

You must set your house

On fire.

Professor Kumar explains that the ‘house’ that Kabir alludes to is the house of one’s own bloated ego and constraining beliefs, and that a true spiritual seeker must confront these aspects of the self in order to gain a glimpse of the divine. “I felt Kabir was beckoning me to remove the veil of ignorance. Because intellectual arrogance is very seductive – it becomes a new kind of veil.” Aptly, the title of Professor Kumar’s new book is Glimpses of the Real in a House of Illusions.

As Professor Kumar studied Kabir’s couplets in the original 15th century Hindi dialect over the following years, he became inspired to trans-create them in English for the world at large. He emphasises that trans-creations are different from translations. That is, rather than trying to reproduce Kabir’s couplets in the couplet form, “It’s poetic prose that takes certain liberties. It is meant to capture some of the beauty of the original without being stilted by its format,” he says. He likens this approach to the popular translation of Tagore’s Gitanjali from Bengali to English, which Tagore himself undertook in collaboration with Irish poet W.B.Yeats.

Painting with words

Kabir’s verses flourished across North India over the centuries as part of a popular oral tradition of India. They were sung and recited in temples, schools and fields by scholars, spiritual seekers and peasants alike. It is only in the last 150-200 years that they were compiled and written down, and were then taken up by academics and educators.

Professor Kumar likens Kabir to a painter working with different colours. He underlines the poet’s “great sense of sound and music for language” and his capacity to “play beautifully with words”. Reciting one of Kabir’s much-quoted couplets in Hindi and English to illustrate his point, Kumar tells how the poet imaginatively uses two words manka and pher several times in the couplet, but with entirely different meanings: manka is ‘rosary bead’ and is also ‘something belonging to the heart’; pher means ‘moving the beads’ and also ‘crookedness of the heart’.

For eons

You have been moving

The beads in your hand

Yet nothing has moved

In your heart

O dear friend

Leave aside the beads

Open your hands

Let the heart

Turn!

Kabir wrote prolifically about love for the divine, and was considered to be a great exponent of the rich bhakti tradition in India, which is characterised by intense love and devotion for one’s personal god. Reciting one of Kabir’s couplets, Professor Kumar elaborates how the poet’s longing for and the experience of the divine seems “utterly sensuous, almost erotic”:

I shall make my eye

Into a bridal chamber

In its pupil

I shall lay the bridal bed

I’ll use my eyelashes

Like silken curtains

And there,

O my Beloved

I shall endear You

For ever

And ever.

Eluding categorisation

While a few things are known for certain about Kabir – like that he lived 500 years ago in the holy city of Varanasi – many other facts about the poet remain elusive. It’s unclear whether he was born a Hindu or a Muslim, yet it is certain that any notions of casteor creed were of no consequence to him.

Neither a Hindu

Nor a Muslim

Am I

A mere ensemble

Of five elements

Is this body

Where the spirit

Plays its drama

Of joy and suffering.

Kabir remained a low-caste marginalised weaver, even though his verses were taken up throughout the city of Varanasi in his lifetime, and touched people across all religions, classes and castes. What distinguishes Kabir from other bhakti poets is his ridicule of all religious and social hypocrisies that tend to obscure the face of the divine. He was a “radical” in this sense, claims Professor Kumar, because he questioned the scholarship of Brahmin pandits, and instead celebrated direct personal experience of the sacred.

If by shaving one’s head,

One could experience

The Divine

O dear friend

How easy

It would all be

See how often

A sheep is shorn

Yet how far from heaven

It is!

Pompous sermons, rituals or dogmatic theological debates were also questionable to Kabir, Professor Kumar explains, because they often arose from habit or pride, rather than from a pure heart.

Sand and stone

They have piled

And they call it

A mosque

And there

O my friends

The priest shouts

The name of Allah

As though

God was deaf.

Kabir paid a price for being so outspoken in India’s holy city, and he was harassed, tortured and even threatened with death. At the same time, he had become so popular by the time of his death, it’s said that both the Hindus and Muslims wanted to claim the poet as one of their own sages. “They were fighting over what to do; whether to cremate or bury him,” narrates Professor Kumar. ”Legend has it, when they removed the shroud, there was no body and only a heap of flowers. So they divided the flowers, and then half were buried and half cremated. So to this day, there are two funeral places for him in Varanasi, one where the Hindus say he was cremated, and the other where the Muslims say he was buried.”

Five hundred years later, many religions and religious (or mystical) movements claim Kabir as one of their sages or saints. They include Sufis, Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Sikhs. He is also claimed by atheists and social revolutionaries with the same enthusiasm. “Even the Marxists claim him as one of their own, a leftist, an ardent socialist!” says Professor Kumar. “Everyone claims Kabir to be one of them. Indeed, his voice has become ever more universal and encompassing, and utterly daring.”

In the last few decades, Kabir’s vision and songs have been popularised in many films and plays, and are performed throughout north India. There are four or five large annual Kabir festivals in India, including the popular Kabir pilgrimage through Rajasthan, in which numerous Aurovilians have participated in the past (including this writer). Kabir’s verses are taught as part of the school curriculum, and many academics have made Kabir’s philosophical nuances the focus of their scholarship. In short, Kabir’s emphasis on direct experience of the divine clearly appeals to a very broad audience.

Sharing Kabir globally

Professor Kumar started his professional life as a physicist, but over the years his concerns grew about the role of science in the war industry, so his academic focus shifted to bioethics, human ecology, and the dialogue between science and religion. “Increasingly,” he says, “I am becoming a student of human civilisation – what it has been, and what it might be.”

Kumar says he wanted to offer his own trans-creations of Kabir to make his vision known globally. He had observed that people at musical performances of Kabir songs often felt “the beauty of the music”, but did not always understand the grandeur of the words. “When I give an explanation of the depth of the words, it becomes a richer experience, I believe.”

Now that he is retired and living in the community as a Friend of Auroville, Professor Kumar has shared his trans-creations at various community events and in radio programmes, sometimes accompanied by a flautist and Indian classical dancers. He has given lectures and public recitations in 30 countries, from Iran to China, and from Russia to the United Kingdom. “I offer them in churches and temples, for students and worshippers. People everywhere seem to be touched by Kabir’s verses. They don’t know the original, but the message of love moves them nevertheless. A few years ago, Kumar recalls, at a Black Church in Alabama, three women came forward after his presentation. “They said, ‘Professor, we feel that Kabir could be our prophet.’ So, Kabir’s message of oneness transcends all distinctions. It was very touching.”

As part of his passion to make Kabir known widely, Professor Kumar is spearheading a large project in Auroville to translate Kabir into ten European and Asian languages. This idea was unexpectedly conceived when Aurovilian Anandi Zhang attended one of Professor Kumar’s sessions three years ago. “She seemed quite moved, and said Chinese poets have a long tradition of writing couplets.” Anandi and Professor Kumar have been working together to publish a bilingual book that presents Professor Kumar’s English transcreations alongside Anandi’s Chinese translations. The book will be published in the near future, as Ocean in a Drop: Kabir’s Couplets in English & Chinese, and the authors hope to do a book tour in China.

Professor Kumar emphasises the timeless and contemporary appeal of Kabir, beyond trappings of any religion or institutions. “In the first quarter of the 21st century, I believe this global civilisation is at a very crucial point in the turning of human consciousness,” he asserts. “Oneness, equality, acknowledgement of all life in its varied and rich fecundity, are all crying out for a place of peace and dignity at the banquet table of history…. That’s why, and how, Kabir is so contemporary, so eternal, and so universal.”

Wherever

My eyes turn

I see

The light

Of my Beloved

O dear friends

When I reached out

to touch it

I too

Became part

Of that light.

Professor Kumar’s books include The Vision of Kabir and 7000 Million Degrees of Freedom. Some videos of his recitations can be seen on Auroville Radio’s webpage and Facebook page.